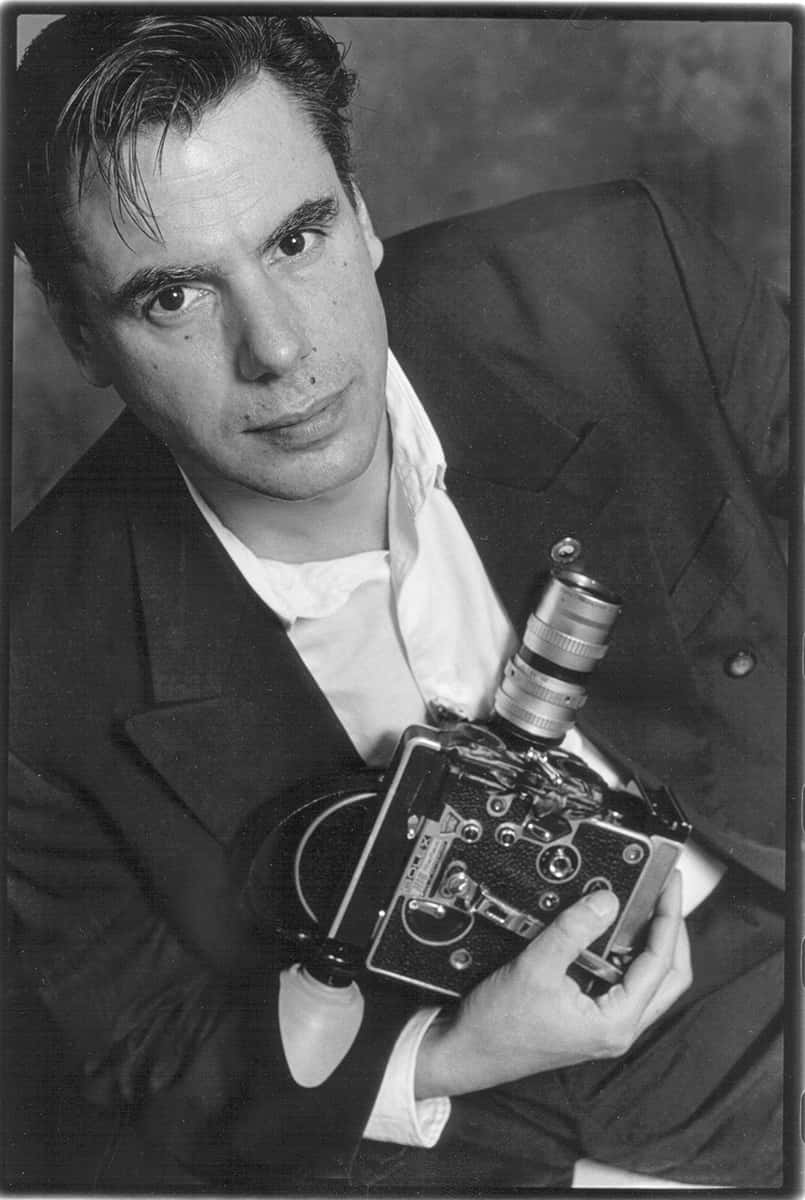

Frank Scheffer

Frank Scheffer (b.1956, in The Netherlands) is internationally recognized as a master of sound and image. He founded Allegri Film Company, which specializes in documentaries on music and art. Scheffer was schooled at the Academy for Industrial Design (Eindhoven), “Vrije Academie” Art College (Den Haag), and is a graduate from the Dutch Film Academy (Amsterdam).

Early films include Zoetrope People (1982), a documentary on Francis Ford Coppola and his studio with Wim Wenders, Tom Waits, Vittorio Storraro and others, as well as documentaries on the Dalai Lama and various socio/cultural subjects. In 1985 he directed the music video A Day for the band XYMOX on the 4AD label, leading him towards musical subjects.

1987 saw his short experimental films Wagner’s Ring, a distillation of The Ring in 3’50” conceived with John Cage; and Stoperas which was created to be shown with Cage’s Europeras 1 & 2.

Collaborations with Cage continued with the conceptual film Chessfilmnoise (1988), a documentary on Cage and Elliott Carter Time Is Music (1988), and From Zero (1995) in collaboration with Andrew Culver.

Scheffer’s films on music constitute an overview of the great composers of the 20th century – from Conducting Mahler (1996) on the 1995 Mahler Festival in Amsterdam with Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Chailly, Riccardo Muti and Sir Simon Rattle; to Five Orchestral Pieces (1994) on Arnold Schönberg’s work conducted by Michael Gielen, and The Final Chorale (1990) on Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Wind Instruments conducted by Reinbert de Leeuw. Further documentaries include Louis Andriessen (The Road, 1997, conducted by Peter Eötvös); Luciano Berio (Voyage to Cythera, 1999), on his Sinfonia conducted by the composer); Pierre Boulez (Eclat, 1993), and Helikopter String Quartet (1986) with Karlheinz Stockhausen and The Arditti Quartet.

In 1999, Scheffer made Music for Airports, ambient video on Brian Eno’s music of the same name as arranged by Bang on a Can founders Julia Wolfe, Michael Gordon, David Lang and Evan Ziporyn. The sprawling In the Ocean (2001), on present day New York composers, features Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Elliott Carter, John Cage, Brian Eno and the Bang on a Can founders.

Scheffer is also working on several in-depth films on specific composers – The Present Day Composer Refuses to Die on Frank Zappa, in cooperation with the Zappa estate (2000, featuring The Mothers of Invention, Pierre Boulez and Ensemble Modern), and the 90-minute Zappa feature Phaze II, The Big Note (2002), to be followed by a third film which will complete his Zappa trilogy. Scheffer has been following and filming Elliott Carter for 25 years; this will culminate in A Labyrinth of Time, a unique portrait on the composer as well as a view of the history of modernism in the 20th century. A feature on Edgard Varèse is planned.

In addition to numerous critical and festival awards, Scheffer was honored with a complete retrospective of his films at the 2001 Holland Festival.

Reviews:

Elliott Carter – Quintets and Voices

John Cage – From Zero

Mode 128 (DVD)

Mode 130 (DVD)

DVDs a la Mode

A classical music video is a predictable affair. One can expect to see wide shots of the performers, with the occasional cuts to the audience and the hall itself to establish the atmosphere. Someone in the control room shows off knowledge of the score as the camera zooms in on a player just about to begin a solo. This annoying practice virtually commands the viewer, “This is what you should be listening to now.”

A different and more rewarding model for how such videos might work is presented in two recent DVDs on Mode featuring films by the Dutch director Frank Scheffer. Focusing on the music of Elliott Carter and John Cage, Scheffer’s works suggest that such films might convey the compositional principles behind the musical works they document. Of course his composer subjects could not be more dissimilar in those principles, and a very different kind of film emerges for each.

The film Quintet for Piano and Strings appears on the DVD Elliott Carter: Quintets and Voices (Mode 128, 2003). It begins in near obscurity behind pianist Ursula Oppens, and the camera seems intent on revealing as little as possible about the identity of the performers. As the Quintet unfolds, the members of the Arditti Quartet gradually come into view, but rarely is more than one player at a time the focus of a shot. The players are attempting to work together, as furtive glances from one to another show, but the gulf between them is wide. A striking sequence early on confirms this. We see Irving Arditti, the first violinst, in a shot from behind cellist Rohan de Saram, looking up toward him with a serious expression. Immediately following we see de Saram from behind Arditti, and we feel almost as if they looked at each other from the opposite sides of a canyon. We also begin to get the sense that the piano is trying to insert itself into the gap, with Oppens visually in the center, striving to communicate with both sides – or perhaps as the driving force in the wedge between them.

Many of the shots that follow are closeups of the players, some decidedly uncomfortable. It is only within the last two minutes of the film that we begin to see something of the big picture, as the camera pans from one side of the quartet to the other. However, we never see all five players together, but an alternation between the viola and cello on one side, and the violins on the other. Grouped with the latter is the piano, which seems to succeed at last in fracturing the quartet. Here the camera feels most expressive, trying to bring the five performers together at the finale. But in a brilliant stroke Scheffer allows the camera to fail and a final unity is never achieved.

Readers who have spent time with Carter’s music will recognize several of its more prominent themes in the structure of the film. Perhaps most notable is how Scheffer captures the intensity of individuality that is at the heart of Carter’s approach to writing for instruments. The film explores the interaction of those individuals in a variety of ways, some more cooperative, some more antagonistic. In fact, while the main tension is between the piano and the string quartet, the latter is not simply singing with one voice, either in the music or in the film. Thus, in idiomatically cinematic ways, Scheffer has produced a visual analogue of Carter’s compositional practice.

This process is more overt in Scheffer and Andrew Culver’s collaboration titled From Zero: Four Films on John Cage (Mode 130, 2004). Of special interest here is a performance of Cage’s work, Fourteen, by the Ives Ensemble. Like all of Cage’s late number pieces, the instrumentalists are assigned parts which contain mostly single notes and chance-distributed time brackets indicating the period of time (as measured by a stopwatch) within which the notes are to be played. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Fourteen is the presence of a bowed piano which contributes sounds of extended duration. The piano, alone, plays continuously, as Cage indicates, “an unaccompanied solo…in an anarchic society of sounds.”

In order to film the work, Scheffer and Culver decided on some anarchic principles of their own, providing Cage-like scores for a team of “undirected camera performers,” for lighting, and eventually for editing. The result is a mesmerizing essay in Cagean “anarchic harmony” in multiple dimensions that enhance one another, facilitated by the shimmering sonorities of complex harmonics that the composer draws from the ensemble. In the film’s most arresting sequence a camera slowly pans across a trumpet and its player, mostly out of focus (characteristically, the trumpet is not being sounded at this point). The trumpet seems like three points of light, then several, and only gradually does the actual form emerge. Meanwhile a complex sound grows out of rich but uncertain harmonics that glisten much as the trumpet does as it moves into and out of focus. As for the solo piano, no one feature of the lighting or editing seems to correspond to it – until one remembers that the only constant through the film is the viewer, alone in an anarchic society of images.

The Carter and Cage DVDs contain additional materials of considerable interest. From Zero includes three other films by Scheffer and Culver, all of which incorporate chance operations to some extent. In 19 Questions, Cage speaks on randomly selected topics for periods of time also determined by chance. In Paying Attention, Culver and Scheffer work like Cage and Merce Cunningham, with Culver manipulating the audio portions of a Cage interview while Scheffer plays with the visual sequences, without either knowing what the other is doing. The last film, Overpopulation and Art, overlays the composition Ryoanji, interpreted both in sound and film, with Cage’s reading of a mesostic recorded in the last year of his life. The result is a moving memorial. Valuable interviews with Culver and Scheffer place the films in context.

The Carter DVD contains an interview with Arditti, Oppens, Joshua Cody and the composer. But the most valuable parts of the DVD are the performances in very radiant sound. The Quintet receives a second, tighter, reading, but there is also the more boisterous Quintet for Piano and Winds and the beautifully paced Syringa and Tempo e Tempi performed by the Ensemble Sospeso. Scheffer’s excellent new Carter documentary, A Labyrinth of Time, will be released soon by Mode. Recently premiered at the 2004 Tribeca Film Festival, it is not to be missed.

—Anton Vishio, Institute for Studies In American Music Newsletter

Volume XXXIII, No. 2, Spring 2004

Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of NY

Frank Scheffer: "Quintet for Piano and Strings":

film on Elliott Carter's piece (mode 128)

John Cage: From Zero (mode 130)