String Quartet No. 2 “mind rock” (2000) (14:06)

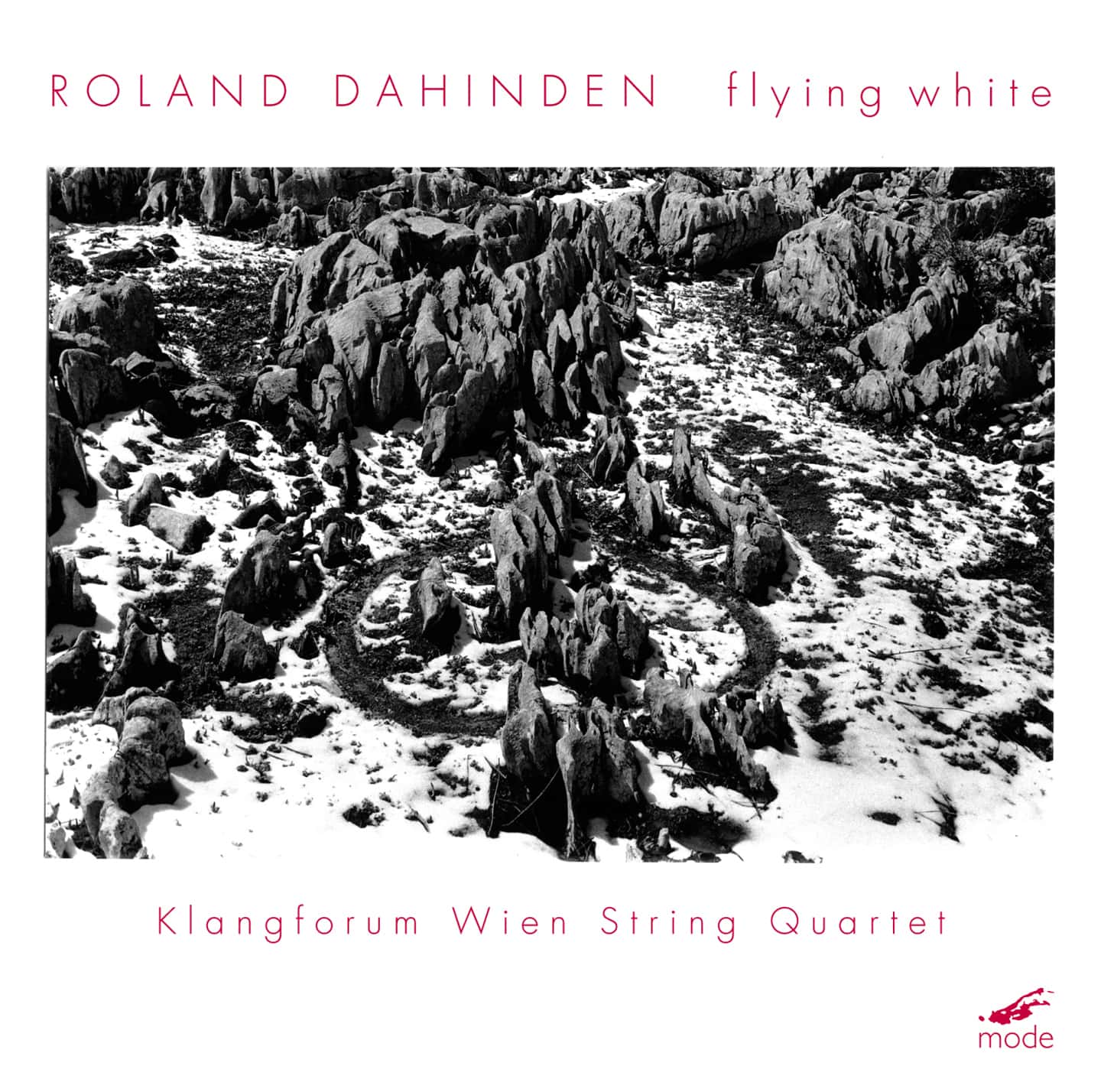

for Richard Long

String Quartet No. 4 “flying white” (2003) (12:02)

for Brice Marden

BINAURAL RECORDING

String Quartet No. 5 “poids de l’ombre” (2004) (24:56)

for Stéphane Brunner

String Quartet No. 3 “mond see” (2001) (14:23)

for Inge Dick

BINAURAL RECORDING

Klangforum Wien String Quartet

Annette Bik and Sophie Schaffleitner, violins

Dimitrios Polisoidis, viola

Andreas Lindenbaum, violoncello

For his third CD on Mode, composer, trombonist, improvisor Roland Dahinden explores the string quartet medium. Each work is dedicated to and influenced by a major visual artist.

Dahinden’s four works refer to images by artists, but at the same time avoids illustrating it in a literal way.

The sounds move through space thanks to a dynamic binaural system recording. Listening with stereo loud speakers, you find yourself towards the periphery of the space, listening with head phones, you are in the centre of the space.

Dahinden was born in Switzerland in 1962.He studied trombone and composition at Musikhochschule Graz (Erich Kleinschuster, Georg F. Haas), Scuola di Musica di Fiesole Florenz (Vinko Globokar), Wesleyan University Connecticut (Anthony Braxton, Alvin Lucier, M.A.) and Birmingham University of England (Vic Hoyland, PhD). As an interpreter and improvisor he performs extensively throughout Europe, America and Asia. He has recorded for MODE and for Black Saint, Braxton House, HAT HUT, Klangschnitte, Lovely Music, and World Edition. He has premiered works written for him by Ablinger, de Alvear, Braxton, John Cage, Lang, Lucier, Newman, Oliveros, and Wolff.

Performed by the string quartet of the outstanding ensemble Klangforum Wein.

Flying White

$14.99

mode 175 Roland DAHINDEN: Flying White – String Quartet No. 2 “mind rock”, String Quartet No. 5 “poids de l’ombre”; Binaural Recordings: String Quartet No. 4 “flying white” and String Quartet No. 3 “mond see”. Klangforum Wien String Quartet, Annette Bik and Sophie Schaffleitner, violins, Dimitrios Polisoidis, viola and Andreas Lindenbaum, violoncello.

In stock

John Cage

One11 with 103

Mode 174 (DVD)

Recommended

Here John Cage joins the elect company of 20th-century musical mavericks – Harry Partch, Sun Ra, Frank Zappa, and Mauricio Kagel – who translated a singular musical vision to film without resorting to a typical biographical or concert documentary. Recently released on a fine DVD by Mode Records, One11 and 103 is a 90-minute black-and-white meditation on the waxing and waning of light: Candle-like apertures appear, expand, then recede from view while Cage’s orchestral work 103 simmers with sustained strings and occasional punctuations from oboe, trumpet, tympani, and other instruments.

— Christopher DeLaurenti, Seattle Film Festival, May 27, 2007

John Cage

One11 with 103

WDR Symphony Orchestra, Cologne/Arturo Tamayo

Spoleto Festival Orchestra/John Kennedy

Mode 174 (DVD)

DVD OF THE MONTH – GRAMOPHONE EDITOR’S CHOICE

A little light music; this atmospheric film could have emerged only from Cage

The 90-minute film of One11 was the major project of Cage’s final years and was completed just three months before his death in 1992. When asked why he took on something new in the medium of film, Cage said he jumped at the opportunity because there wasn’t much time left. Sadly he was right.

The music is a seamless garment of continuous sustained sounds, with some individual notes picked out, in the style of Cage’s late “number” pieces. There’s a choice of two soundtracks that are independent, of course, from the visual images but nevertheless uncannily appropriate. Cage said the film has “no plot, no characters, nothing”, hoping it would “give pleasure without having any meaning whatsoever”. He wanted it to be “free of politics, economics and even of oneself”. The documentary material with the DVD shows that the film was elaborate to make: there are 17 scenes requiring 1,200 cues with 20 light-changes each – all indicated in charts for the technicians derived from Cage’s usual chance methods. The camera is the soloist.

These details don’t explain the remarkable quality of these uniquely pure visual images, studies in light ranging from total black to total white. No colours. The play of lights brings up slowly moving circular objects eerily reminiscent of distant moons transmitted from outer space posing the eternal questions of existence. At times the scenario suggests cloud formations viewed from a plane. Cage’s formulae for removing personal taste have paradoxically produced mesmeric images that only he could have devised.

Cage himself is interviewed but understandably seems tired compared with the sparkle of his younger self. But what a splendid project carried out with dedication by all concerned.

— Peter Dickinson, Gramophone, April 2007

John Cage

One11 with 103

WDR Symphony Orchestra Köln/Arturo Tamayo; Spoleto Festival Orchestra/John Kennedy

Mode 174 (DVD)

John Cage explores the visual equivalent of silence

One11 is a visual counterpart to Cage’s ‘silent’ composition 4:33, questioning our concepts of emptiness. ‘No space is empty,’ he said. ‘Light will show what is in it.’

The film is ‘about’ the play of light on more-or-less plain surfaces, shot in gritty black-and-white: I guess shooting in colour would have made it a film about light and colour, rather than pure light. It’s also about the movements of the lights and camera, devised in advance by a computer programme, created in consultation with the random principles of I Ching.

The DVD also contains an interview with cinematographer Van Carlson and director Henning Lohner and a 43-minute documentary, during which Cage indicates the film should give pleasure without having meaning. What makes it art is the meditation of artists. I frequently derive pleasure from watching the play of sun/moon/firelight on the ceiling whilst listening to birdsong or a favourite record, but that surely makes me a slacker, not an artist.

The film is accompanied by two versions of the orchestral work 103, created quite independently of One11, but also lasting 90 minutes and including the same number of ‘episodes’ (17). The version recorded at the premiere by the WDR Symphony Orchestra is notably more softly-focused than that by the Spoleto Festival Orchestra, but the drifting shapes and the constantly evolving textures of both interpretations help the time pass far more enjoyably.

— Barry Witherden, BBC Music Magazine, March 2007

John Cage

One11 with 103

Mode 174 (DVD)

Something about nothing: John Cage

As new releases of John Cage go, this is probably about as major as it gets. “The first commercial release of Cage’s only feature-length film,” the back cover trumpets, but, Cage being Cage, this film is about the material of the film making itself. There’s no plot or characters – in fact, no human form is seen on the screen for the 90 minutes stretch of its duration. Instead, a cameraman, guided by chance procedures derived from the I Ching, manipulates constantly evolving patterns of light and shade against a fixed backdrop.

Echoing his wisecracking aphorism “I have nothing to say and I am saying it”, Cage confirms that his film is about “nothing” in the accompanying documentary. He underlines his central credo that sound should not be representative of anything else other than itself, and transferring these principles to film in 1992 was a natural development. Cage had increasingly involved himself with visual art throughout the 1980s and boundaries became somewhat arbitrary. Why not give instructions to flautists, singers and also cameramen?

One11 begins with a long series of credits and the line that every auteur aspires to see: “A Film By John Cage”. The acknowledgements include nods towards Frank Zappa and Dennis Hopper, and the film itself splutters into being like an abstract pre-talkie flick. The black and white grainy quality of the picture allows for a rich palette of tones and textures, and the images are so disarmingly striking that your eyes can’t help but listen carefully.

There are extras for the ears, too. Viewers can choose between two different performances of Cage’s orchestral 103 (1991) to accompany, and the counterpoint between visual and sound is ample proof of how holistic Cage’s vision had become. The sounds are otherwordly and hovering. Occasionally the orchestral monolith melts to allow underlying details sufficient oxygen, or gets broken by thunderous percussion whacks. Cage himself looks frail and died shortly after One11 appeared. But what an extraordinary valedictory throw of the dice.

— Philip Clark, The Wire, February 2007

John Cage

One11 with 103

Mode 174 (DVD)

In 1992, John Cage declined several invitations to attend celebrations marking his 80th birthday in order to devote himself to the completion of One11, the eleventh work for solo performer (hence the title) in the series of Number Pieces that occupied him during the five last years of his life. The performer in this case was a solo cameraman – Van Carlson – and Cage’s ambitious project was nothing less than a full-length film (90 minutes) with no characters and no plot, directed by Henning Lohner and accompanied (or not as the case may be) by the orchestral work 103, which dates from September 1991. It’s quite simply one of Cage’s great works, and one of the most complex and time-consuming to realise, though as usual the basic idea was remarkably simple: use I-Ching generated chance procedures to determine the placement, angle of projection and intensity of 168 lights in an empty television studio and provide the solo cameraman with a similarly calculated score defining camera movements (a similar chance-generated working plan was subsequently devised for the editing of the film that took place in New York after the film had been shot in Germany in April 1992). The film consists of 17 scenes, each of which is further divided into takes, and Cage’s idea was to dispense with editing as far as possible; amazingly only 600m of film were not used, and were duly pillaged to provide the visual backdrop to the opening credits. Andrew Culver programmed the composer’s calculations into a computer which controlled the lighting changes – some 1200 of them, each featuring up to twenty different lights – and the full resources of the studio in Fernseh Studio Munchen were put at Cage’s disposal.

Shot entirely in 35mm black and white, One11 consists of predominantly slow pans across the blank wall of the studio, illuminated by soft oval patches of light of varying intensity that drift across the screen like clouds. It’s a remarkably beautiful experience in conjunction with the rich sustained chords and occasional spiky twangs of 103, two versions of which are included on the disc as alternative soundtracks, one performed by the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln conducted by Arturo Tamayo, the other by the Spoleto Festival Orchestra conducted by John Kennedy. The disc also includes two documentaries on the creation of the film, including insightful explanations by the people involved and some choice quotations from Cage himself. When asked why he’d finally decided to venture into film, he answers: “if I get an opportunity to do something, I jump at it instead of hesitating. Because there isn’t much time left.” And, later: “In this day of violence, overpopulation, war and economic collapse, it gives us something to enjoy.” It does indeed.

— Dan Warburton, ParisTransatlantic Review, January 2007