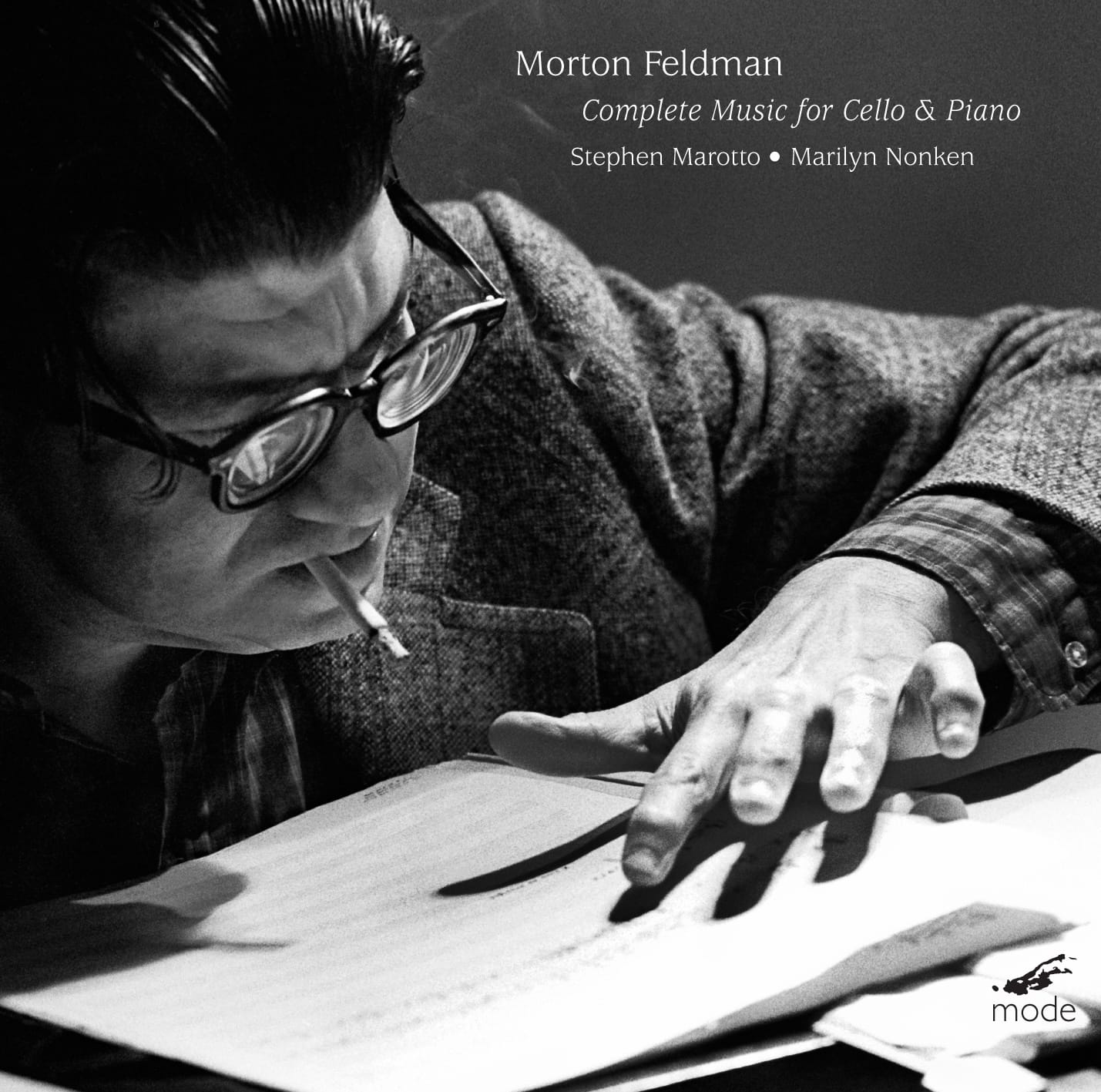

Complete Music for Cello & Piano

MORTON FELDMAN (1926–1987)

Complete Music for Cello & Piano

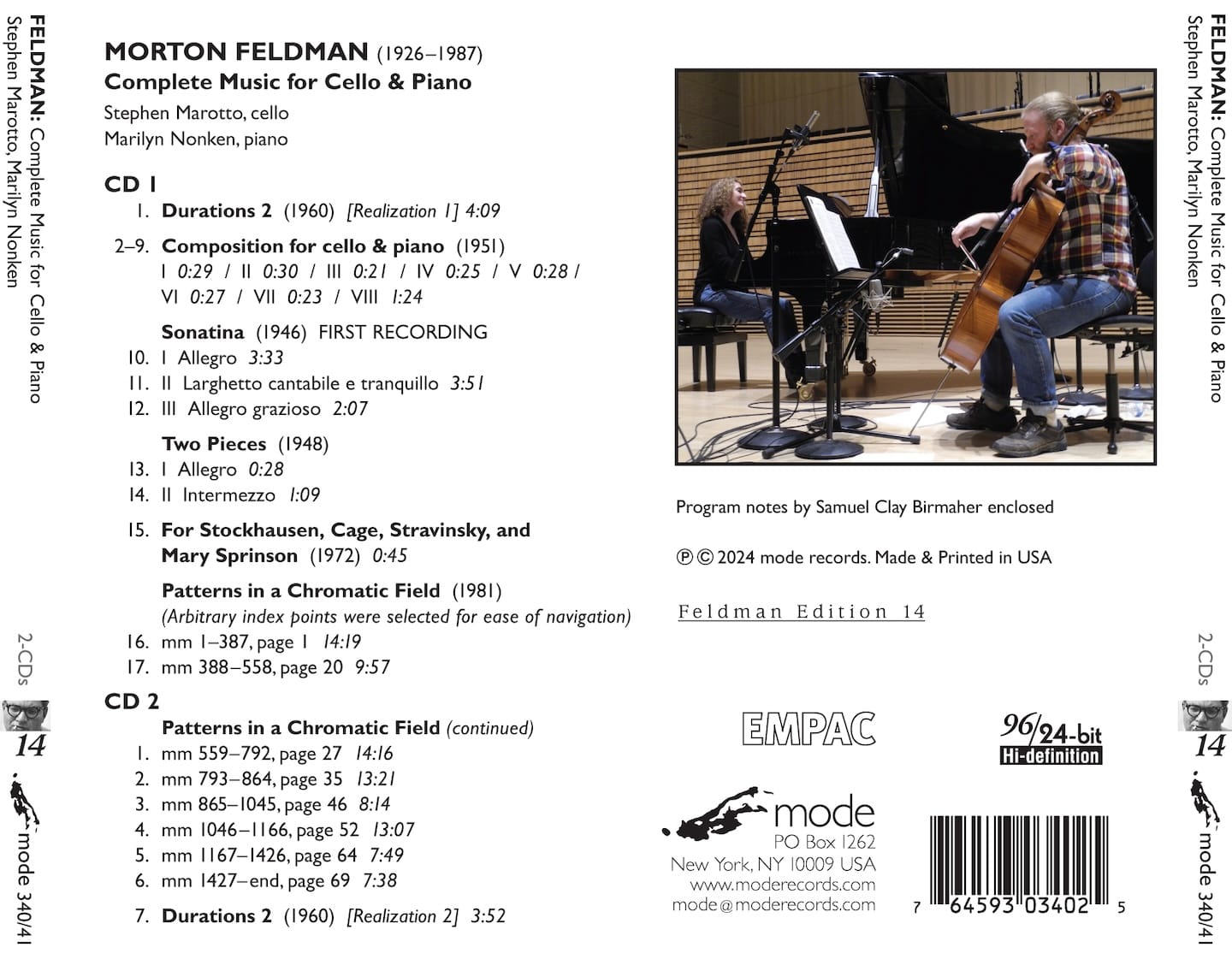

Stephen Marotto, cello

Marilyn Nonken, piano

CD 1

1. Durations 2 (1960) [Realization 1] 4:09

2–9. Composition for cello & piano (1951)

I 0:29 / II 0:30 / III 0:21 / IV 0:25 / V 0:28 / VI 0:27 / VII 0:23 / VIII 1:24

Sonatina (1946) FIRST RECORDING

10. I Allegro 3:33

11. II Larghetto cantabile e tranquillo 3:51

12. III Allegro grazioso 2:07

Two Pieces (1948)

13. I Allegro 0:28

14. II Intermezzo 1:09

15. For Stockhausen, Cage, Stravinsky, and Mary Sprinson (1972) 0:45

Patterns in a Chromatic Field (1981)

(Arbitrary index points were selected for ease of navigation)

16. mm 1–387, page 1 14:19

17. mm 388–558, page 20 9:57

CD 2

Patterns in a Chromatic Field (continued)

1. mm 559–792, page 27 14:16

2. mm 793–864, page 35 13:21

3. mm 865–1045, page 46 8:14

4. mm 1046–1166, page 52 13:07

5. mm 1167–1426, page 64 7:49

6. mm 1427–end, page 69 7:38

7. Durations 2 (1960) [Realization 2] 3:52

This release brings together ALL of Morton Feldman’s compositions for cello and piano, including unpublished works and a first recording.

Together, these works tell the story of Feldman’s music. They span 35 years — over half his lifetime — from when he was searching for his voice as a student to when he was opening new doors in the last years of his life.

The album is bookended by two realizations the graphic score “Durations 2” (1960), giving an opportunity to hear what the flexibility of graphic notation can bring.

The “Sonatina” (1946) is earliest work here, and a first recording. Displaying the influence of Béla Bartók, Feldman wrote for the cello sound he loved without fully understanding the realities of playing the instrument. The resulting solo part is naively virtuosic and often even impossible to play. For this recording, Stephen Marotto keeps as close as possible to the written score, aiming to fulfill what Feldman heard in his mind’s ear.

By 1948, Feldman had been studying privately with the composer Stefan Wolpe for several years. The unpublished “Two Pieces,” of that year is a fluctuating music held together not by logic, but through its carefully poised gestures — what Wolpe called “shape.” While the emotional drama of this and other early works would soon disappear from Feldman’s music, it was above all the idea of “shape” that remained with him for the rest of his life.

In 1950, Feldman met John Cage, who shepherded him into the world of the New York avant-garde. The unpublished, compact, “Composition for cello and piano” (1951) is a sudden breakthrough, yet it already contains the DNA of his very last works in its minimal material and blurred memories of sounds.

“For Stockhausen, Cage, Stravinsky, and Mary Sprinson” (1972) is an ephemeral, unpublished piece, a shard of music broken off from the main body of work Feldman was producing at the time. It consists of just two musical moments separated by silence — the same chord expressed in two different ways.

At almost 1 hour 29 minutes, “Patterns in a Chromatic Field” (1981) is of Feldman’s late, long duration period of works and it perhaps the best known of the works recorded here.

Liner notes by Samuel Clay Birmaher.

Reviews

“Completeness” always appeals. Indeed, this double-set is an excellent way to appreciate Feldman’s breadth, though honestly, Patterns in a Chromatic Field, not just because it’s the longest, is the collection’s focus. The “complete” umbrella yields up a juvenile Sonatina, two brief pieces from Feldman’s “study” with Wolpe, a small collection written the year after the pivotal meeting with Cage (Composition for cello and piano), a graphic piece in two performances (Durations 2), and a scrap with a curious title (For Stockhausen, Cage, Stravinsky, and Mary Sprinson).

New to the world is the first recording of the once 20-year-old composer’s Sonatina. Written without actual familiarity with the cello, some parts are impracticable. Suggesting a collection of Soviet-era miniatures, Feldman’s tonal motifs prefer both players’ high registers.

Patterns is an excellent onramp into Feldman’s late style. The ideas are distinctive, the material immensely varied and compelling. As the not-quite-identical repetitions flow past, there are sublime moments and places where you just have to laugh out loud.

I have always marveled at Patterns’ opening: Like a simmering hurricane, the cello oscillates unevenly across four notes while the piano emits staggered chords. On paper, we see metric and harmonic complexity: the cello must subdivide an 8/32 measure into 9, the piano’s corresponding 4/16 measures may require division into 5s or 3s. Pitches are spelled in a typically obtuse late-Feldman fashion: the cello has B-double-flat, A-flat, F-double-sharp, A-sharp in its first collection while the piano is limited to D, E-flat and F-flat. Seeing a diminished third (D to F-flat) at the top of a chord is so strange.

I could listen to Patterns all day. Considering releases mentioned before (Mayr and Anissegos, Marco and Giancarlo Simonacci, and Deforce and Oya), I appreciate Marotto and Nonken’s fluidity and intentional disunity. Knowing the piece, it’s refreshing to hear two people playing together in a boldly disinterested fashion. The repeats surprise more as do the changes of mood. At near 90-minutes, this marathon is less about delivering Feldman, but a continual game of leapfrog where piano or cello may lead, or separate, or get stuck.

— Grant Chu Covell, © 2024 La Folia

This is Morton Feldman’s Complete Music for Cello & Piano, but it might just as well be Patterns in a Chromatic Field, etc., because that work dominates this release in terms of quantity and quality. (OK, Durations 2 is pretty good too, but it is much shorter.) There is a recording premiere here, and that is the Sonatina, as yet unpublished, which was composed when Feldman was 19 or 20. I doubt anyone would identify Feldman as its composer on the basis of the music alone. The booklet note by Samuel Clay Birmaher suggests that “its crunchy harmonies and rhythms stem from Bartók.” Well, maybe. I find it to be clever and rather cute—and “cute” is not a word one associates with Feldman’s music. I can hear readers asking, “Who the hell is Mary Sprinson?” Mary Sprinson, it so happens, was Feldman’s girlfriend in 1972, the year in which this work was composed. It’s only 45 seconds long, so if you divide the work equally into four slices, one for each of the personages mentioned in the title, Mary’s slice is a little over 11 seconds. I wonder if she felt shortchanged.

Patterns is the pièce de résistance here, and it has done well in the CD era. Presto Classical lists seven different recordings, and there are others beyond those. Marotto and Nonken play it in 88:45, so it starts on the first CD and occupies all of the second CD, apart from the second realization of Durations 2, which comes at the very end of this collection. This is almost exactly as long as Arne Deforce’s and Yutaka Oya’s excellent recording on Aeon—shorter than some, and longer than others. The opening pages seemed almost frantic to me, but I think that has more to do with the musicians’ articulation and attack than with actual tempos. This, in fact, strikes me, overall, as the most violent and the least detached, or at least the most confrontational, recording of Patterns. (I read a description of Patterns that described its opening—music that reappears, approximately, later in the work—as being like the sound of a couple arguing in the next apartment. I am paraphrasing, but you get the idea!) Much of the work is meant to be played quietly, sometimes almost at the threshold of silence (ppppp), but Marotto and Nonken alternate near-stasis with passages that startle and annoy, even if you keep the volume down—which typically is what you are told you “should” do in Feldman’s late works—but you do you, as they say. That said, if you are fascinated by this work, Marotto and Nonken might give you a new perspective on it, and that might be reason enough to acquire this recording, although I will stick to Deforce and Oya, who are cooler and more refined than the performers on this CD. In any case, Feldman completists will want this CD because it is Volume 14 in Mode’s Feldman Edition, a worthwhile project to be sure, particularly when it brings us unrecorded works.

—Raymond Tuttle, © 2024 Fanfare

The title of Patterns in a Chromatic Field invites a visual analogy to the American school of abstract expressionism that sprang up in New York after the war. If we could train or at least encourage our ears to listen to Feldman the way we look at Rothko or de Kooning, we might come closer to the essence of the music. Cello and piano circle around each other, forming patterns and then decomposing them. They share a melody, and pause for thought over an element of it. This in turn leads them further away from, or back towards, the distinctive slithering motif that begins the piece.

Just because this form of expression takes place in time, it need not lead anywhere: this was John Cage’s discovery, and before him Erik Satie’s. Feldman learned from his friend Cage, and from the music of Webern, to build an interior world that rejects the need for continuity, or even pulse. Once we cease waiting for something to happen, Patterns becomes among the most eventful (action-packed would be pushing it) of Feldman’s long late pieces.

Compared to Rohan de Saram and Marianne Schroeder (hatART, 9/17), Stephen Marotto and Marilyn Nonken take a relatively flowing approach to tempo, not that they are in any hurry. Nonken has recorded Feldman’s piano output for the Mode label, and she understands this hermetic world from the inside. The sound is drier than for Arne Deforce and Yutaka Oya (Aeon, 8/09), but it complements Marotto’s lighter bowstrokes.

The early miniatures include graphic scores, one of which (Durations 2) is presented in two (not very) different realisations. The discovery (and first recording) is the Sonatina, which the 20-year-old Feldman wrote in 1946. In his helpful booklet essay, Samuel Clay Birmaher says that the solo part is ‘naively virtuosic and often unidiomatic or even impossible to play’. Marotto stylishly overcomes such challenges and leaves the impression of a composer searching for his own voice within the later music of Bartók and Prokofiev. Thank goodness he met Cage.

— Peter Quantrill, Gramophone, September 2024

With his 1981 masterpiece Patterns in a Chromatic Field, Morton Feldman continued his journey into long-form works that toyed with the real-time memory of his listeners. In these slowly cycling compositions, the sort of intricate irregularities woven into the patterns of Turkish rugs were translated into carefully measured sound. That piece for piano and cello occupies the bulk of this stunning double-CD release, exquisitely performed by Marilyn Nonken and Stephen Marotto, respectively. The set collects all of Feldman’s work for this configuration of instruments, including the first ever recording of his 1946 piece “Sonatina,” written in the shadow of Bartók. The 1951 work “Composition for cello & piano” is a set of seven super-short movements that feel like raw material he would later refine and embroider within long form works. There’s also “Two Pieces,” a pair of miniatures from 1948, when the composer was studying with Stefan Wolpe, and the previously unpublished 1972 vignette “For Stockhausen, Cage, Stravinsky, and Mary Sprinson.” The set opens and closes with two very different performances of “Durations 2,” one of his earliest experiments with graphic notation. While the pitch material is fully mapped out, there’s no indication of the duration for each note, with both performers taking their own path while remaining mindful not to tangle the sounds up. As evidenced here, no performance is ever the same. Still, the apex of Feldman’s writing for piano and cello remains Patterns, a viciously tough piece to play, casting a deceiving spell of serenity while requiring the players to maintain hyper-focused concentration.

— Peter Margasak, The Best Contemporary Classical Music on Bandcamp, March 2024, posted April 1st.