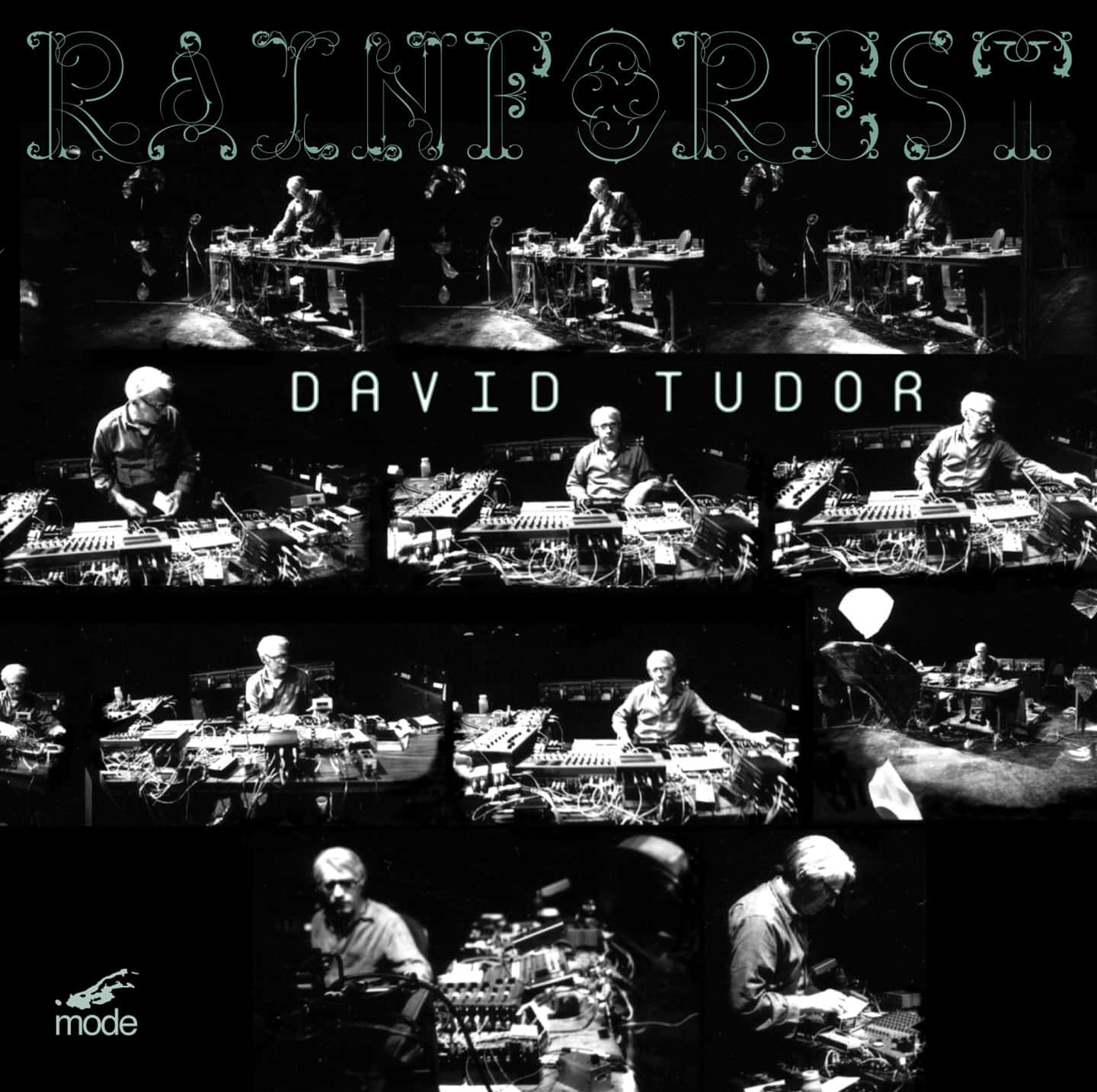

Rainforest - Versions I (1968) & IV (1973)

His electronic environment masterpiece in 2 different versions:

Rainforest Version I (1968) (21:47)

for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

David Tudor & Takehisa Kosugi, live electronics

Sliding Pitches In The Rainforest In The Field: Rainforest Version IV (1973) (51:58)

an electro-acoustic environment

David Tudor, who passed away in 1996, was a brilliant musician whose musical career can be viewed in two parts. He was as “the” foremost avant-garde pianist of the 1950s and 60s – the great piano works of that period were in his repertoire, with countless premieres and compositions written for him by Brown, Cage, Stockhausen, Bussotti, Feldman, La Monte Young, Wolff, Wolpe and others.

Tudor gradually traded in the keyboard to turn his attention towards composing for live electronics. His influence and effect on electronic music is as great as it was towards the piano. Tudor became an integral musician for The Merce Cunningham Dance Company with John Cage in the 1950s, a career which encompassed both aspects of his musicianship.

RAINFOREST is one of Tudor’s landmark works. It exists in 4 possible performance versions, 2 of which are on the present CD and issued commercially for the first time.

To describe RAINFOREST is completely impossible. Like the real rainforest, it has too many moving parts. To describe how it works is only a little less difficult. To hear it in operation, however, is an unforgettable experience. Surrounding and engulfing the listener, RAINFOREST blends music and sculpture by placing music in space in extraordinary ways.

The idea is to channel electronic output through an object rather than through the usual device, a loudspeaker. Dozens of unique and unlikely objects are suspended from the ceiling at about ear level. The space is filled with gentle sounds given off by the vibration of the hanging objects. Tudor could pick up the vibrations of any of these objects via a contact microphone, feed it back into his controls for filtering and mixing, and then redistribute the sound out again to some other object or a conventional loudspeaker. The recycling phenomenon that takes place makes the entire electro-acoustic apparatus of RAINFOREST an “ecologically balanced sound system.”

The result is a timeless sonic environment full of rich textures offering the listener an infinite variety of aural densities and spatial effects. Intensely alive and unlimited, it is a masterpiece of composition.

Reviews

David Tudor

Rainforest I and IV

Mode 64

I could start and end my recommendations with Rainforest I (1968), a groundbreaking phenomenon like nothing else before or since. Written for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Rainforest I is captured in a 1990 live performance by Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi on mode 64. Rainforest I is on my list of the best electroacoustic works of all time, and if at the end of this article you have but the slightest interest in Tudor, you must hear this CD. You actually should stop reading now, head on over to http://www.moderecords.com/ and order it.

You probably have an idea of what a rain forest sounds like, thanks to tourism, nature TV and movies. Rainforest I is bound to disrupt all that. Rather than field-recording a rainforest, Tudor created an electronic fantasy absent ambient nature samples and similar clichés. Rainforest I consists of complex, homemade electronic circuitry manipulated in real time by Tudor and Kosugi to create something alien yet curiously organic. You will hear itchy-crawly electronic circuits pulsing, whirring and chirping. I’ve been to Costa Rica and experienced the real thing: Nothing in nature sounds anything like this.

Mode 64 also includes another electroacoustic environment, Rainforest IV (1973). Some of the musicians who worked with Tudor on Rainforest IV believe that this recording doesn’t do the work justice; nonetheless, you must snap up this mode CD.

— Grant Chu Covell; from “David Tudor, Performer and Composer of Live Electronic Music: A Survey of Available Recordings“, La Folia Online Music Review, April 2003

David TUDOR

RAINFOREST

I’ve got this problem with my Walkman: every time I pass a shop window with neon lights, or someone passes me using a mobile phone, it buzzes, clicks and generally interferes with whatever I happen to be listening to. However, I don’t mind if I’m listening to Cage, or to one of his “school”–I always took that “let sounds be themselves” line to be the perfect excuse for hanging on to scratchy vinyls that I would otherwise have returned straightaway to the shop–the crackles and fizzes go very well with this fine new recording of David Tudor’s “Rainforest.” Tudor was of course legendary as Cage’s right hand man for many years, firstly as an exemplary pianist, later as sound designer and long-standing partner in their collaborations with Merce Cunningham, for whom “Rainforest” was originally conceived in 1968. Fewer people know Tudor the composer, and the relative paucity of recorded work hasn’t helped–apart from the long-deleted Lovely album with “Pulsers” and “Untitled”, what else has there been? Well, I once saw a vinyl of “Rainforest” (one of Cunningham’s more memorable creations, thanks to Andy Warhol’s free-floating helium-filled Mylar pillows) in a junk shop in Rochester, New York. That was just the first version of the piece, a 21-minute performance of which–by Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi–makes up the first part of this disc; “Rainforest” evolved over the years into a group composition/installation featuring input from John Driscoll, Phil Edelstein, Bill Viola and others. A number of objects are suspended from the ceiling in a large performance space and made to vibrate and resonate as sound-producers, Tudor typically recording, mixing and playing back the resulting sound into the installation, making “the entire electro-acoustic apparatus… an ecologically balanced sound system” (Gordon Mumma). The second piece on this disc, “Sliding Pitches in the Rainforest in the Field Rainforest Version IV”, is a montage of recordings made in the installation (at the ICA in London?) by John Driscoll. As such it is but a snapshot of a vast landscape, but an absolutely fascinating one. Extended post-ambient drifting is certainly in vogue right now–if you have recently invested in Pauline Oliveros and the Deep Listening Band, the empty soundscapes of Thomas Küner, or the hurdy-gurdy ramblings of Keiji Haino, then “Rainforest” is right up your street, if you’ll excuse the mixed metaphor. Brilliant.

—Dan Warburton, Paris Transatlantic Review, November 2000

TUDOR STILL AWE-INSPIRING 30 YEARS LATER

David Tudor

Rainforest I & IV

Mode 64

I first heard Rainforest I in ’73 during a performance by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, where it was relayed over a multi-channel system. Being seated in the upper circle, and not having previously attended a Cunningham performance, I had no idea that the entire piece was probably being performed live in the orchestra pit by David Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi. Along with Cage, they toured regularly with Cunningham, providing live musical accompaniment. The publicity, however, did not bill the composers as live participants, merely listing each music title alongside each dance title. Since the pit was not visible from the circle, I simply assumed that the whole piece was on tape. When I attended my next Cunningham performance several years later — this time in the front row — I found myself seated inches from a jungle of electronic circuitry, amplified cactus plants, and miscellaneous pieces of Tudoresque bricolage. Throughout the performance, Cage, Tudor, and Kosugi bent intently over their consoles, apparently oblivious to all of the vibration taking place on the stage above them, while creating music which meshed harmoniously with the movements of the dancers.

In combination with Cunningham’s wonderfully abstract choreography, Rainforest I made a surreal and hallucinatory impression that has haunted me ever since. I am pleased to report that the intensity of that experience has been captured for me by this long-awaited recording, on which Tudor and Kosugi perform. Why such music has been kept on ice for thirty years and only released after Tudor’s death defies explanation (this version was recorded in New Delhi in 1990, but there have been numerous others since 1968). The entire piece sounds at first like an ethereal insect chorus, but the layers gradually disperse into patterns of jagged counterpoint, which in the performance seemed to harmonize perfectly with the movements of the dancers (although there was no synchronization, the musical and choreographic processes being entirely independent). Most of the sounds are created by sine tones being reverberated through a forest of suspended metal containers, pieces of junk that function as “biased” loudspeakers imparting their own timbral colouration to the sounds which pass through them. These sounds are picked up by contact microphones, fed back into Tudor’s mixing and filtering controls, and then recycled back into the expanding forest of increasingly hybrid noises. The array of metal containers usually fills an entire gallery, and spectators are invited to walk around and put their heads inside the containers. The rendition I heard in ’73 presumably involved a slimmed-down “orchestra” that would fit inside the orchestra pit, but I shall probably never know for certain. Also, it’s of interest to note that Cage and his collaborators — who in the ’60s also included Gordon Mumma — were not always confined to the orchestra pit. Apparently, in the early ’60s the musicians would clamber around on stage, communicating over walkie-talkies, amplifying parts of the floor, stretching amplified wires, etc, and miraculously not colliding with the dancers. The dynamic level was also considerably higher, leading one critic to comment that attending a Cunningham performance was like trying to watch ballet in the middle of an airfield.

Rainforest I can only be described as awe-inspiring, and my one regret about it is that it doesn’t continue any longer than its slender 21’47”. The version that previously appeared, on Edition Block Grammavision vinyl, was twice the length but very inadequately recorded. Rainforest IV, which completes the present disc and is also performed by Tudor and Kosugi, is of more substantial duration but makes a less powerful impression because the recording is poorly balanced, with some elements strongly foregrounded and others recessed in shadowy vagueness. The result is nevertheless impressive. In this realization of the piece, layers of reverberation create an ocean mass of sound, as metallic and glassy splinters are filtered through layers of resonance. The work creates a rather floating, dreamlike impression, evoking the calls of unglimpsed sea creatures echoing through the dark of the ocean. Both works embody the warmth, humanitarianism, and love of nature which one immediately recognized in Tudor. His spirit lives on through his music.

— Roger Sutherland, Musicworks, Number 75, Fall 1999

Rainforest (Version I and IV)

David Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi, live electronics

Mode 64

A student of Stephan Wolpe and a pal of John Cage, David Tudor (1926-1996) led two lives in America’s postwar musical scene. As a pianist, he gave scrupulously prepared, premiere performances of works by Boulez, Bussotti, Feldman, Stockhausen, Wolpe, Cage and others, and thus, in the words of Nicolas Slonimsky, “was a touchstone and at times even a catalyst for the composition of a body of music of often extreme radicalism.” As a composer, Tudor explored the freedoms of the avant-garde and the growing interest in the potential of electronically generated sounds to forge a unique body of dense, intriguing soundscapes that could seem simultaneously random and carefully preconceived.

Rainforest, premiered in 1968, was created for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company with which Tudor was affiliated from its inception. The original performance (Version I) took place in a large New Hampshire barn where the rafters were suspended with various objects that vibrated when struck. These sounds were picked up by microphones, fed back into controls for the composer’s manipulation, and redistributed through conventional loudspeakers. To these created sounds, and amidst a set of helium-filled mylar pillows designed by Andy Warhol, the Merce Cunningham dancers did their thing. Version II of Rainforest added an electronic processing of John Cage’s voice, and in Version III the music was overlaid by Cage’s reading of selections from the writings of Thoreau. Version IV grew out of a group workshop in 1973, with a number of cutting-edge composers contributing the final electronic concoction.

On this important Mode Records CD, Version I (22 minutes long) and Version IV (52 minutes long and additionally titled Sliding Pitches in the Rainforest in the Field) are offered. Although the listener at home can neither stroll through the hanging instruments nor observe Cunningham’s choreography, one can certainly enjoy and even succumb to the fascinating evolution of percussive and electronically generated sounds that ebb and flow, thicken and dissipate, astonish and mesmerize.

— Richard Perry, Ottawa Citizen, November 1, 1998

John Cage, Cartridge Music (Mode 24)

David Tudor, Rainforest (Mode 64)

John Cage may not have invented electronic music, but he certainly had a lotof good ideas before anyone else. As early as 1937, Cage predicted the useof electronic instruments to add “noises” to the musical palette, to helpavoid the comfortable sounds most music presents to us. In 1939 he composedImaginary Landscape No. 1, which used variable-speed phonographs andrecordings of frequency tones, plus muted piano and cymbal. ImaginaryLandscape No. 2 (1941) was scored for percussion instruments, including agiant metal coil electronically amplified by a phonograph cartridge.Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (1951) was limited to 12 radios; of course,depending on the broadcasts, the music was totally unpredictable. Aware ofPierre Schaeffer’s experiments beginning in 1948, Cage produced ImaginaryLandscape No. 5 (1952) for sounds drawn from 42 LP recordings to be cut upand reorganized on magnetic tape, and Williams Mix (1942), which used morethan 500 pre-recorded sounds spliced and pasted together on tape. Arguably,Cartridge Music (1960) was an even more radical step. Cage and David Tudorattached contact microphones and phonograph cartridges to various householdobjects — furniture, ladders, waste baskets — and replaced their needleswith wires, matches, pipe cleaners, feathers and the like. By physicallyhandling all these objects, they invented a spontaneous, indeterminate, liveform of musique concrète. Notwithstanding Cage’s graphic instructions tofocus the performers on their task, the procedures produce mostly minusculepercussive sounds that resemble incidental activity more than music-making –a reasonable extension of Schaeffer’s ideas.

David Tudor was a brilliant pianist and conceptualist, without whom manyimportant scores of the 50s and 60s would neither have been composed norrealised. But he gave up the piano in order to concentrate on his ownelectronic compositions, most of which used sound systems devised ormodified by himself (as heard on the Lovely Music reissue of Three WorksFor Live Electronics). Rainforest is an exception, borrowing Cage’s idea ofattaching microphones and cartridges to unconventional objects and thentreating the amplified sounds with his own electronic system. This CDcarries two of the four existing versions of Rainforest: Version I, forTudor’s and Takehisa Kosugi’s live electronics, and Version IV, a recordingof an installation where audience members interact with sound generatingobjects, creating an alien landscape that rumbles, hums, groans and whines.Tudor’s Rainforest choice for the record is quite arbitrary — you could belistening to a three-dimensional sculpture garden, or be in the pit of MobyDick’s stomach.

—The Wire, August 1998

David Tudor

Rainforest: Versions I & IV

Mode 64

As a pianist with a career – long association with Cage and Stockhausen, David Tudor knew well the sound world that the Electronic Music Centre was intent on exploring. Rainforests I & IV (recorded in 1968 and 1973 respectively) show how far Cage had loosened the parameters. Rainforest I, for live electronics by Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi, shares characteristics with much of the EMC work, not only electronically speaking but more especially in its spatial design. Unsurprisingly, the piece was made for theatre: it was danced by Merce Cunningham’s company in a set augmented by Andy Warhol’s helium-filled cushions. Part IV is 51 minutes of dense, yet lush environmental electroacoustic music. And as for the missing variations? The second, with Cage’s voice, was never recorded, and the third, on which Cage chanted from a Thoreau-inspired text, was for simultaneous performance only.

— Louise Gray, The Wire, July 1998

David Tudor

Rainforest (Versions I & IV)

Mode 64

David Tudors live-elektronisches Meisterwerk Rainforest liegt nun endlich auf CD vor. Die in Zusammenarbeit mit Takhisa Kosugi für die Merce Cunningham Dance company entwickelte achtkanalige Lautsprecherfassung (I, 1968) bereitete die skurrile Klanginstallation vor (IV, 1973), in der in Ohrenhöhe von der Decke hängende Metallobjekte als Lautsprecher fungieren. Tudor lässt seine table-top-electronics sirren und fiepen und etabliert eine dichte, von kurzen Schleifen dominierte Klangwelt voller bezaubernder Prozesse und überraschender Übergänge. Ein Avant-garde Klassiker.

— Volker Straebel, Der Tagesspiegel, 5. Juli 1998