Cage Edition 48-Variations V

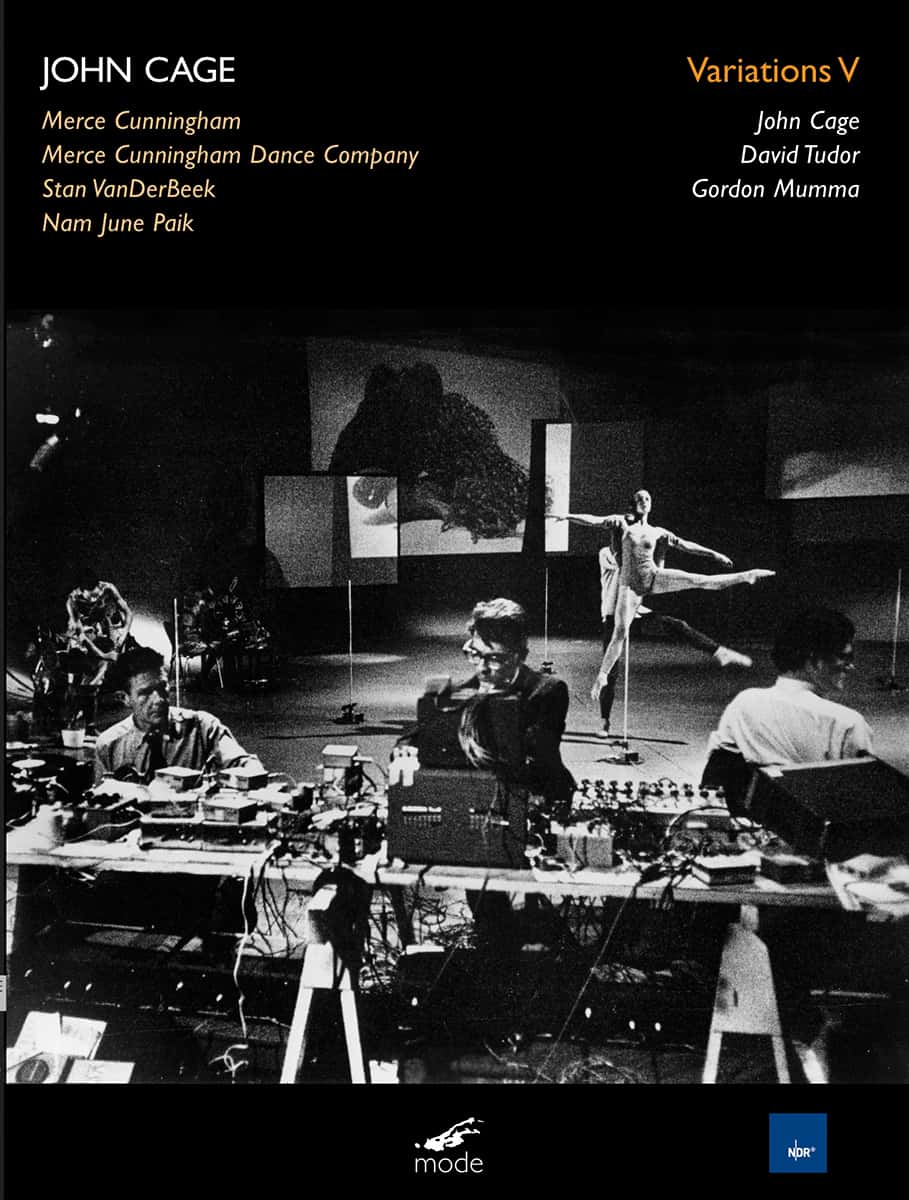

Variations V reflects the experimentation and spirit of the 1960s — a collaborative, interactive multi-media event with choreographed dance, elaborate mobile decor, variable lighting, multiple film projection, and live-electronic music often activated by the dancers’ movements.Filmed in 1966 at the NDR television studio in Hamburg, Germany, it is historically important as one of the few available films of a Cunningham Dance Company performance from the 1960s and the first commercial release of Variations V. As the dancers performed on stage, their movements interacted with twelve antennas built by Robert Moog and a set of photocells designed by Bell Labs research scientist Billy Klüver in such a way as to trigger the transmission of sounds to a 50-channel mixer whose output was heard from six speakers around the hall. The actual sound sources—a battery of tape recorders and radios—were supervised by Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma. The mise-en-scène was supplemented by a film collage by Stan VanDerBeek that included processed television images by Nam June Paik and footage of the dancers shot by VanDerBeek during rehearsals. Recorded at Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR). Previously released as DVD. This video includes the original introduction from the German broadcast of Cage's Variations no. 5, an audio recording of a performance the piece in Paris, as well as an interview lead by David Vaughan of two participants in the original production. Electronic reproduction. Alexandria, VA : Alexander Street Press, 2013. (Dance in video, volume 2). Available via World Wide Web.

Variations V (1965) 47:13

NDR-Hamburg German Television version 1966 (mono, PCM audio)

with introduction by Hansjörg Pauli

Musicians: John Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma

Choreography: Merce Cunningham

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company: Merce Cunningham, Carolyn Brown, Barbara Lloyd, Sandra Neels, Albert Reid, Peter Saul, Gus Solomons, Jr.

Filmed Projections & Visual Effects: Stan VanDerBeek and Nam June Paik

Lighting: Beverly Emmons

Directed for Film by Arne Arnbom

Variations V (1965) 39:37

Paris version 1966 (stereo, PCM audio only)

Musicians: John Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma

Variations V reflects the experimentation and spirit of the 1960s — a collaborative, interactive multi-media event with choreographed dance, elaborate mobile decor, variable lighting, multiple film projection, and live-electronic music often activated by the dancers’ movements.

Filmed in 1966 at the NDR television studio in Hamburg, Germany, it is historically important as one of the few available films of a Cunningham Dance Company performance from the 1960s and the first commercial release of Variations V.

As the dancers performed on stage, their movements interacted with twelve antennas built by Robert Moog and a set of photocells designed by Bell Labs research scientist Billy Klüver in such a way as to trigger the transmission of sounds to a 50-channel mixer whose output was heard from six speakers around the hall. The actual sound sources—a battery of tape recorders and radios—were supervised by Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma. The mise-en-scène was supplemented by a film collage by Stan VanDerBeek that included processed television images by Nam June Paik and footage of the dancers shot by VanDerBeek during rehearsals.

157 minutes of video and music.

BONUS FEATURES:

• A complete stereo recording of the Paris 1966 performance of Variations V (PCM audio, no video, 40 minutes).

• Cunningham Dance Company’s archivist David Vaughan interviews some of the dancers from the original production — Carolyn Brown (40 minutes), and Sandra Neels with Gus Solomons Jr. (30 minutes) — about the production, working with Cage and Cunningham, and touring in the 1960s.

• 12-page book with essays by Rob Haskins and Gordon Mumma plus archival photos.

Language : English.

Reviews

Was Jasper Johns tat, damit ein Freund von ihm künstlerisch einen Tänzerfuß in die Tür kriegte

Manche mögen sich fragen, warum ich an dieser Stelle wieder und wieder auf Merce Cunningham zurückkomme und ob der Blog nicht besser „Invitation to the Dance of Merce Cunningham“ hieße. (Happy Birthday August Bournonville! * 21. August 1805) Nun, ein Grund ist, dass ich in der Kunstwelt ständig Menschen begegne, mit denen im Gespräch über die Lage des Tanzes die Rede wie selbstverständlich auf Cunninghams Einfluß kommt.

Steve Paxton (*1939) etwa, der bis zum Ende der ersten Welt-Tournee 1964 für ihn tanzte, hat mir jetzt in Berlin erzählt, warum er am Ende der Londoner Vorstellungen damals ging. Es waren keine künstlerischen Gründe. In Paxtons berühmtestem Solo, den natürlich Jahrzehnte später entstandenen „Goldberg-Variationen“ tritt deutlich zutage, welche ähnlichkeiten zwischen den gleichermaßen charismatischen Performern Cunningham und Paxton bestanden – was Männer wie sie dem maskulinen Tanz jenseits der Prinzenrollen, der Gentlemen Balanchines oder der Sexobjekte Martha Grahams an Repräsentationsmöglichkeiten eröffneten. Paxton verließ die Company, weil er spürte nach diesen Monaten, in denen die Tänzer mit John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg und Merce in einem VW-Bus gemeinsam die Welt umrundet hatten, dass sich alles ändern würde mit den großartigen Erfolgen beim Publikum und bei der Kritik. Eine Art Stille vor dem Sturm war eingetreten, es gab noch keine neuen Auftrittstermine, keine konkreten Pläne, nur war klar, dass mit den jetzt veröffentlichten englischsprachigen Sensationskritiken aus der Alten Welt endlich, nach neun Jahren, auch eine größere amerikanische Öffentlichkeit auf die Kunst von Merce Cunningham, John Cage und Robert Rauschenberg aufmerksam werden würde. Paxton sagt, es sei einfach herrlich gewesen, eine so lange Zeit auf engstem Raum miteinander zu verbringen und sie hätten soviel gelacht. Ihm sei klar geworden, dass diese Art zusammen Kunstwerke entstehen zu lassen, sich mit der Berühmtheit ändern würde und das wollte er nicht miterleben. Das Beeindruckende an seiner Schilderung waren die noch nach so langer Zeit unerbittliche Entschlossenheit Paxtons, die Willensanstrengung hinter der Entscheidung und sein gleichzeitiges Bedauern des Unabänderlichen. Vielleicht ist es das – ich habe noch nie jemanden getroffen, der mit Merce Cunningham und seinem Werk in Berührung gekommen wäre und nicht um ihn und jedes einzelne Stück, das wir vielleicht nie wiedersehen werden- auf wie verschiedene Weise auch immer – trauerte.

Darum nun zu einem weiteren Stückchen Vergangenheitsbewältigung, ohne das die Gegenwart weniger lebendig wäre. Vor einiger Zeit habe ich hier angekündigt, dass das New Yorker Label www.moderecords.com (Mode. PO Box 1262. USA – New York, NY 10009) Cages und Cunninghams „Variations V“ (1965) auf DVD herausgibt, und zwar eine Filmaufnahme des Stücksvon 1966, die in den Hamburger Fernsehstudios des NDR entstanden ist. Dazu später.

Die BONUS FEATURES bestehen aus einer kompletten Tonaufnahme ohne Bild, die von einer Pariser Aufführung im selben Jahr stammt und langen Interviews des Archivars der Merce Cunningham Dance Company mit Tänzern, die an der Produktion beteiligt waren: Carolyn Brown, Gus Solomons Jr. und Sandra Neels sprechen mit David Vaughan. Paxton war ja schon nicht mehr dabei.

Vaughan erzählt, mit den Aufführungen von „Variations V“ habe Cunningham erstmals einen Fuß in die Tür des New Yorker „Lincoln Center“ bekommen. Die Premiere fand in der Philharmonic Hall statt, heute Avery Fisher Hall. Jasper Johns habe übrigens etwa zur selben Zeit ein Bild gemalt, auf dem Merce Cunninghams Fußabdruck verewigt wurde – um diesen dabei zu unterstützen, wie Vaughan Johns’ Worte erinnert – „einen Fuß in die Tür zu kriegen“.

Das als Vorwort, geht es in medias res. Das ist ein weiterer Grund, sich mit Merce Cunninghams Arbeit zu befassen. Wann immer von ihr die Rede ist, wird nicht drumherumgeredet, sondern es kommen sofort eine Menge Fakten, wie sich das Stück erklärt, warum etwas so oder so gemacht wurde. Alle große Kunst hat faszinierende technische Aspekte, die eng mit ihrer Bedeutung zusammenhängen.

Zum Beispiel lernt man aus dem, was der Tänzer Gus Solomons Junior erzählt, welche Tricks Choreographen gegenüber ihren Mitarbeitern so einsetzen. Merce wollte, dass Solomons in einem Solo beide Hände wie einen Rahmen um seine rechte Hüfte aufspannte und er sollte dabei mit seinem Hüftknochen eine Acht beschreiben. Und jedes Mal, wenn er es Merce zeigte, habe der „Nein, nicht ganz“, gesagt, und schließlich sei es diese nervöse Energie von Solomons gewesen, der beim Tanzen darüber nachgedacht habe, ob seine Hüftacht wohl richtig sei, die das Tanzen energetisiert habe. Also müsse es wohl das gewesen sein, was Merce schlußendlich gewollt habe.

Carolyn Brown erinnert sich, dass zum Zeitpunkt des Probenbeginns Merce seinerseits nervös gewesen sei, weil ihm John Cages musikalische Pläne und ihre Auswirkungen auf die Choreographie noch relativ unklar gewesen seien. Außerdem hatten damals nicht nur Paxton, sondern auch alle anderen Tänzer ihn verlassen – bis auf Brown. Er schuf vierzig Minuten Tanz in drei Wochen, darunter einige phantastische Soli für sich selbst. Das Stück beginnt mit dem Yoga-Kopfstand von Solomons’ Partnerin Barbara Dilley Lloyd.

Was die Filmaufzeichnung sehr gut wiedergibt, ist das aufregende und damals vollkommen neue Multimedia-Gemisch akustischer, filmischer und tänzerischer Eindrücke. Der Bühnenaufbau allein ist ein Hochtechnologie-Parcours. Stabantennen, die den Tänzern bis an die Taille reichen, sind im Kreis aufgestellt. Von ihren Sockeln führen auf dem Fußboden verklebte Kabel zu der Technik-Plattform, auf der John Cage, David Tudor und Gordon Mumma sitzen zwischen „Paraphernalia“, wie Vaughan das nennt, Radios, Tonband-Maschinen, Klangproduzierenden Maschinen. Vorproduzierte Klänge werden gemischt mit den Sounds, die entstehen, in dem die Tänzer um die klangempindlichen Antennen und die Fotozellen herumtanzen. Stan van der Beeks und Nam June Paiks Filmprojektionen und visuelle Effekte auf der rückwärtigen Leinwand sind ebenfalls nach dem Collageprinzip zusammengestellt und bestehen aus Ausschnitten von Spielfilmen, Aufnahmen der Tänzerkörper in vorausgegangenen Proben und geometrischen Farbanordnungen.

Standen die Musiker auf, wurden sie Teil der Leinwandprojektionen als Schattenfiguren. Das Stück wurde in einzelnen Partien gefilmt, dennoch für vierzig Minuten Länge in einem Drehtag sehr schnell. Der Verantwortliche Hansjörg Pauli, Leiter der Abteilung Musik beim NDR Hamburg damals, dessen Anmoderation für die Erstausstrahlung zu sehen ist, erzählt, er habe das Zufallsprinzip in der Regie übernehmen wollen und zwei Versionen hergestellt. John Cage habe ihm gesagt, er solle an Tagen, an denen er braune Anzüge trage, die zweite Version vorführen, an Tagen in grauem Anzug die erste. Man sieht dann die zweite Version. Aber die Anmoderation ist auch in Schwarzweiß (? Weiß frühes Fernsehen schon, was Fernsehen ist?) Immerhin passierte der Unfall, den Merce auf dem Fahhrad erlitt, mit dem er am Schluß des Stücks um die Antennen herumfuhr, nur einmal, nämlich bei der Premiere in der Philharmonic Hall: Der Plan war, vom Fahrrad abspringend sich irgendwo festzuhalten und in der Luft zu baumeln. Stattdessen knallte Merce mit dem Kopf gegen einen für ihn zu niedrigen Gassenausgang. Aber, wie Vaughan erzählt, machte sich Merce nichts aus Verletzungen oder Unfällen. Der Topfpflanze in „Variations V“ ging es schlimmer an den Kragen. Mikrophonverkabelt hereingetragen, riß Merce ihr Blätter aus bevor Brown sie später nicht weniger geräuschvoll umtopfte.

Manchmal ist es in der Kunstgeschichte doch erstaunlich, womit genau man so einen Fuß in die Tür kriegen kann. Und wieviele Beispiele man dafür finden kann, dass es einfach unmöglich ist, sich mit Merce Cunningham zu langweilen (siehe oben).

— Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine, 21 August 2013

The mode video document of ‘Variations V’

It would be fair to say that, for its time, ‘Variations V’ was the most ambitious mixed-media creation involving live performance and real-time control of electronic equipment. That “time” was the summer of 1965, since the work was first performed on July 23, 1965 as part of the French-American Festival at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. It took place in Philharmonic Hall, which would later (in 1969) be renamed Avery Fisher Hall and, at the time, was one of only two completed buildings on the Lincoln Center campus. (The other was the New York State Theater.)

In simplest terms one could say that “Variations V” consisted of a score that John Cage had conceived for choreography by Merce Cunningham; but that would be an oversimplification. It would be more accurate to say that it was a pioneering experiment in the creation of a work that would involve a relationship between the activity of the dancers and the sounds that would accompany the dance. That relationship was realized through two (analog, this was 1965) technologies, twelve proximity-sensing antennas (built by Robert Moog along the principles behind the antennas that control a theremin) and an array of photocells designed by Billy Klüver, each of which would serve as an independent on-off switch, depending in whether or not it detected the presence of light. With this equipment the antennas would emit control signals based on how close dancers were to them, while the photocells would detect when a dancer was blocking the beam of light that it sensed.

The results of all of those possibilities for interaction could best be interpreted as control signals. What further distinguished “Variations V” was the prodigious variety of what those signals would control. Taking the theremin as a point of departure, there were voltage-controlled oscillators (which would later become fundamental components when Moog started to build his synthesizers). However, there was also voltage-controlled amplification of a large array of tape recorders and radios, all combined through a 50-channel mixer. If that was not enough, the dancers performed in front of screens on which a film collage by Stan VanDerBeek was projected; and VanDerBeek’s source reels included television images processed (and distorted) by circuitry designed by Nam June Paik.

As might be guessed, the set-up time for a performance of “Variations V” was enormous; and taking it on tour involved carting around a massive volume of equipment. Nevertheless, the work was taken on tour in both the United States and Europe following its (single) performance at Lincoln Center, with the last performance taking place on May 24, 1968 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Fortunately, when the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) visited Hamburg in 1966, NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk) filmed it for broadcast on television.

The creation of that film was as impressive as the creation of the piece itself. Much of the physical management of all that electronic equipment was determined by a score created by Cage, which required most decisions being made on the basis of chance operations. This was a perfect example of Cage’s philosophy, which was not intended to create chaos but rather to impose a strong discipline of deciding, in advance, what decisions would have to be made, after which the actual decision making would be left to an aleatoric operation. The NDR production team respected this discipline in their own work, meaning that both video capture (how many cameras and where were they pointing) and subsequent mixing were subjected to Cage’s approach to the use of chance.

I never had an opportunity to see “Variations V” in performance. However, through the good graces of the Merce Cunningham Dance Foundation, I was able to see a film of the NDR production during my graduate student days, most likely some time in 1970. I was therefore enthusiastically delighted to learn that last month mode records released a DVD of that video production as the 48th volume in their The Complete John Cage Edition series.

Indeed, through that video I was finally able to experience the NDR broadcast with thorough understanding. The film I had seen as a student included an introduction by its producer in German without subtitles. Thus, my appreciation of that introduction was, at best, fragmentary. The DVD now provides the subtitles I had previously missed so much.

Nevertheless, what really matters is the performance itself. In this filmed version there is almost no sense of chaos, although one is not always sure just what control functions all those sensed signals are performing. The core of the experience still resides in the choreography. Those familiar with Cunningham know that, even when he followed Cage’s disciplined use of chance operations, the result would be dance steps that did not require “on-the-fly” decision making. Thus, as one gets to know Cunningham’s work, one comes to recognize that there were particular tropes through which he would realize the movements of his dancers (just as George Balanchine had his repertoire of tropes for classical ballet). Those tropes could be either very gradual, during which one could appreciate how the movement would unfold in space, or they could involve a joyously energetic unfolding of the movement is a brief duration of time.

As a result, much of the choreography could actually be extracted from the wash of media in which it was embedded (and Cunningham himself would do this for performances arranged for non-theatrical spaces, such as galleries, which he would call “events”). Nevertheless, the superposition of that choreography in a “dissonant landscape” of flickering movie images and sounds from innumerable sources clearly expands the experience of the performance. As NDR chose to render than experience for a telecast, it was abundantly rich without necessarily being overwhelming. Indeed, for those fortunate enough to be able to look back on the full scope of Cunningham’s repertoire, “Variations V’ may be viewed as a first step towards his other resource-rich collaboration with Cage, “Roaratorio.”

In all fairness, however, it may be worth noting that the experience of the observer of “Variations V” would probably not align well with that of the dancers. The mode DVD includes two interviews conducted by MCDC archivist David Vaughan with those who performed “Variations V.” The first is with Carolyn Brown, who does little to conceal her frustration with the work without (hardly) ever trying to be disagreeable about it. The second is with Sandra Neels and Gus Solomons, Jr. Now, to be fair, I should observe that Solomons graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology about a year or two before I entered there as a freshman; so I was not particularly surprised that he would be the most sympathetic of the three in his appreciation of all of the ancillary technology required. Nevertheless, listening to these three dancers is a bit like listening to the monologs in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, so differing are their points of view.

It may be a bit too trivializing to say to the NDR video “it is what it is.” However, this is the sort of performance that is best taken on its own terms but is flexible enough to leave it to the observer to decide what those terms are. Watching the dance is an absolute delight, particularly now that MCDC has disbanded. Does the technology matter? Perhaps the most important thing about the NDR production is that the technology does not dominate. That leaves the observer free to decide how much (s)he wants it to matter.

—Stephen Smoliar, examiner.com, August 19, 2013

Cage’s work in the 1960s recognized the vital new role that technology was already playing (and would come to play) in artistic expression in general, and music in particular. Tape, light, (relatively) easy control of sound and sight in performance; the admixture of these to “conventional” compositional techniques; and the resulting evidence that the sum of such a multimedia, multidisciplinary work as Variations V would always be greater than its parts.

Those parts, those aural and visual components, were taped sound (much of it apparent random and white “noise” (though always gentle, controlled), processed spoken word, multiple vaguely symbolic objects, back projection, superimposition of symbol, scene and sequence – both familiar and unfamiliar. And dance. Variations V is a homogeneous work, 40 minutes long, which does indeed combine Cage’s music (not a conventionally melodious “score”) with the choreography of Cage’s partner, Merce Cunningham. Although performed worldwide at the time, filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek teamed with projection and “effects” specialist Nam June Paik to record a performance in 1966 at the NDR television studio in Hamburg. One of the few (remaining/surviving) films of a Merce Cunningham Dance Company, this DVD is a record, Yes, of a single event. But it’s presented by Mode in such a way that the context and the historical significance of this aspect of Cage’s work are almost as important. It shows just how vital to Cage directed experiment was; and an almost complete deconstruction of what makes a work of art.

Those who don’t/didn’t know what to expect from Cunningham will/would probably have been surprised by the choreography. By the fact that the dancers’ actions and positions on stage electronically determined the content of the sound and projected visual experience. But, one hopes, they’ll understand and be inspired by Cage’s vision of inventing and executing a totally collaborative work which – as this DVD amply shows – thoroughly integrates music and sound, kinesthetics and movement, video and visual stimuli.

This extraordinary and invaluable DVD from Mode ironically captures another attribute of Cage’s work at this time: the notion that music, art must no longer be tethered to the finished object, complete performance or the mounting of occasions with aspirations to the definitive. Rather, we get more out of our engagement by acknowledging – by celebrating – its status as an environment under development. Indeed, in the lengthy and illuminating interviews with Carolyn Brown by David Vaughan which are also featured on the DVD says she preferred the rehearsals to the actual “ performance”.

Not that the performances of Variations V could ever be mistaken for an amateurish mishmash of son and lumière. They’re full of a restrained energy, of a calm knowledge that something significant and important was happening as Cage’s collaboration with Cunningham, Mumma and Tudor evolved. Knowing just in how many ways Variations V were performed subsequently (the booklet that comes with the DVD lists almost 22 in the 1960s) helps us understand which forces worked – and how they worked. The variations reveal the common threads, the essences.

This DVD is as much a historical document as it is a record of a major work by Cage from almost half a century ago. Vaughan’s interviews also reveal just how “ spontaneously” Cunningham and his team (purely technical… electricians, riggers, engineers; and musicians, dancers, performers) worked. Contemporary notes which Carolyn Brown reads suggest, if not conflict between Cunningham and his team, a fair degree of disorganization and unpreparedness. Charitably, one would react to this (now) by labeling as “indeterminate” unplanned and inconsistent dance moves and effects – especially with the “props” (bicycles, chairs, pot plants and so on) that are so integral to the work – and hence seeing them as consistent with Cage’s vision.

Also on the DVD is a stereo audio (PCM) track of Variations V. Although it must not be forgotten that (for Cage, surely) the work should be seen in its own right as something worth engaging with, the concise and focused booklet written by Rob Haskins with notes by Mumma himself and Michelle Fillion (Canadian musicologist, and Professor of Music at the University of Victoria, British Columbia) emphasizes Cage’s role in the work: Variations V was one of eight such numbered pieces with – typically – no conventional score; only written instructions which outlined the work’s conception. Although the booklet contains a brief bibliography, (extracts from) Cage’s writing would have been useful here. Nevertheless, this DVD is one which not only aficionados of Cage, but also those curious about just how vibrant musical experimentation was in the 1960s, will want to own.

—© 2013, Mark Sealey, Classical Net