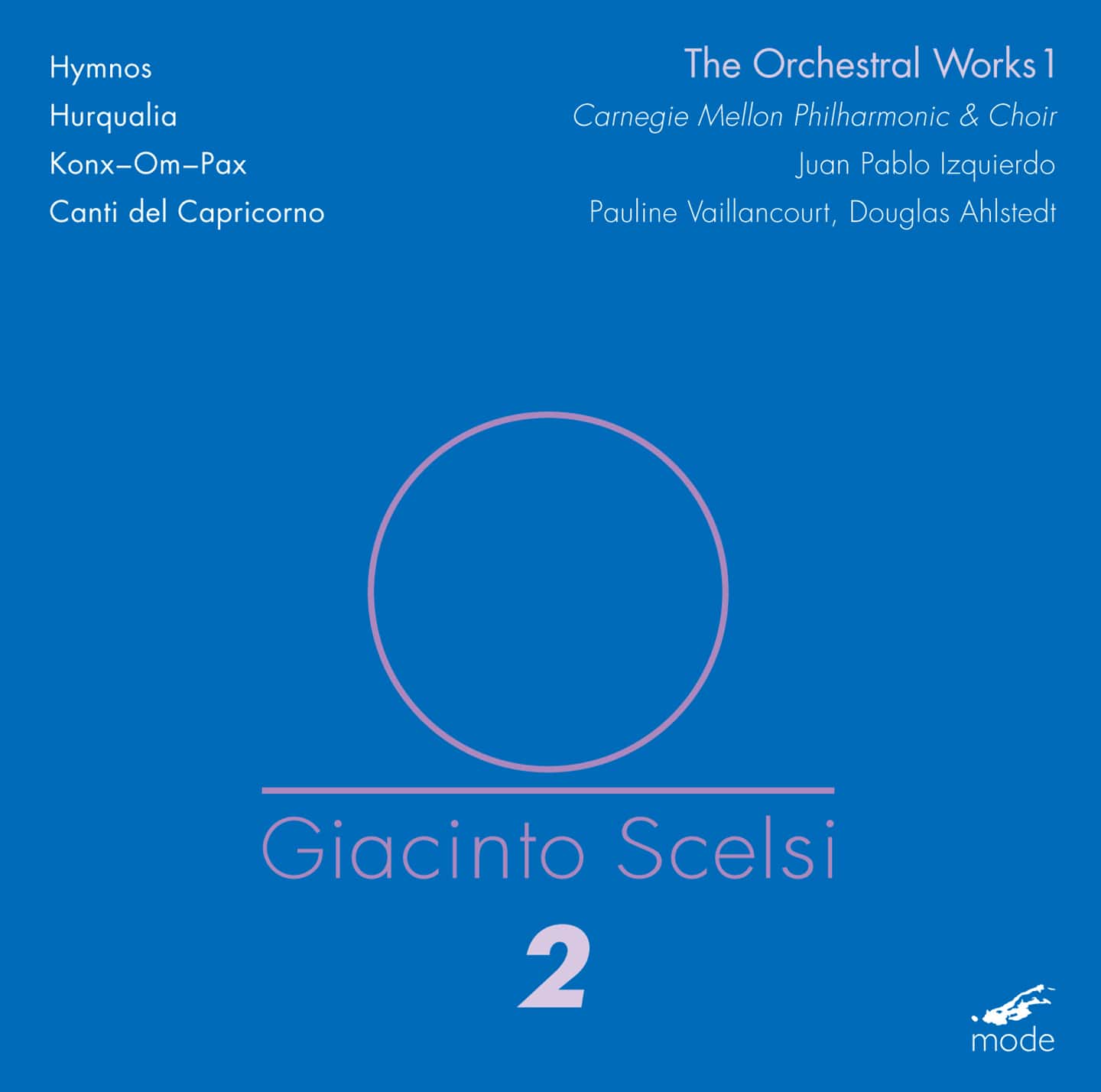

Scelsi Edition 2-The Orchestral Works 1

Hymnos (1963) for organ & 2 orchestras (10:59)

Hurqualia (1960) for large orchestra (4:37, 2:43, 4:02)

Konx-Om-Pax (1968) for large orchestra & chorus (5:41, 2:11, 9:59)

The Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic & Concert Choir

Juan Pablo Izquierdo, conductor

Canti del Capricorno (1962-72)

Canto No 1 for soprano & percussion (3:33)

Canto No 2 for tenor (2:30)

Canto No 14 for tenor & percussion (3:08)

Canto No 15 for soprano (2:50)

Canto No 18 for soprano & percussion (1:57)

Canto 19 for voices & instruments (2:33)

Pauline Vaillancourt, soprano

Douglas Ahlstedt, tenor

Volume 2 in Mode’s Scelsi Edition presents three of his rarely heard and recorded orchestral works, vividly captured in outstanding sound.

Hymnos’ large orchestra is divided antiphonally into two almost identical groups, symmetrically placed on each side of a central axis made up of the organ, timpani, and percussion. About halfway through the piece, as a result of accumulated pedal tones and their harmonics, the aura of a phantom choir miraculously appears-or so it seems-in a spine-tingling sonic revelation.

Hurqualia was written at the height of the composer’s maturity. As with Hymnos, Scelsi obsesses on a single note-in this case a different note for each of the four movements. It reveals a shocking Scelsi: violent, impulsive, loud, fast.

Konx-Om-Pax is the word ‘peace’ in three languages: ancient Assyrian, Sanskrit, and Latin. This 20-minute work for choir and orchestra is his crowning achievement. The orchestra is the largest ever assembled by Scelsi, projected onto an enormous landscape of sound. The joining of ‘all’ in the third movement, combining the massive forces of orchestra and choir, makes an inevitable allusion to a previous ‘ode to joy.’

The orchestral works are interspersed with selections from Canti del Capricorno. A collection of twenty songs, some of the Canti are written specifically for soprano voice, while for others the exact voice is not specified. Improvisation and ‘personal inspiration’ play a large part in the interpretation of the songs. Presented here are some for solo voice and others with instruments, performed by soprano Pauline Vaillancourt and tenor Douglas Ahlstedt.

A student of Hermann Scherchen, Juan Pablo Izquierdo’s interpretations of the Viennese masters of the 19th century continue a long-standing European tradition, while also being internationally for his bold interpretations of avant-garde music of the 20th century. His first Mode disc with the superb Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic garnered rave reviews.

<br

Reviews

Scelsi Volume 1 – The Piano Works 1

Louise Bessette, piano

Mode 92

Scelsi Volume 2 – The Orchestral Works 1

The Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic & Concert Choir

Juan Pablo Izquierdo

Mode 95

Scelsi Volume 3 – Music For High Winds

Carol Robinson, Clara Novakova, Cathy Milliken

Mode 102

Scelsi Volume 4 – The Piano Works 2

Stephen Clarke, piano

Mode 143

Referring to Giacinto Scelsi (1905-1988) as Italy’s Charles Ives is both on and off the mark. Like Ives, Scelsi’s brilliantly radical and idiosyncratic music only gained recognition at a late stage in the composer’s life. Both were ultimate inner-driven composers. In other respects they are polar opposites. New England’s solidly bourgeois Ives studied music at Yale and became an insurance executive. Scelsi was an independently wealthy Count who trained in a very eighteenth-century way via private mentoring. After thriving as a virtuoso pianist, composer, poet and essayist in interwar Paris, Scelsi turned intensely private. While Ives drew inspiration from American vernacular music, Scelsi learned music and religion in India. He then created a deep hybrid of Asian and European musical structures. Three of the four phases of Scelsi’s compositional path, plus one shining selection from the final period, are represented to date in Mode’s important series of Scelsi recordings. Phase one (1930-43) involved Scriabin, futurism, atonality, and dodecaphony. The Piano Suite 2 (1930) on Volume 4 already presents an attention to overtones that would inspire Scelsi’s microtonal, “three-dimensional” music. Phase two begins with an extended nervous breakdown and Scelsi’s creation of a new musical system as a vehicle for self-healing. He focused on complex nuances that could be generated from a single note. Scelsi’s practice of Buddhist meditation and Yoga was integral to the attentiveness that attuned him to microtonal consequences of individual sounds. Beyond pitch and duration, this was music’s third dimension. Through 1956, Scelsi composed mainly for piano. Real-time composition was part and parcel of his new musical system. In the late 1940’s, Scelsi tape-recorded piano improvisations. His ample wealth permitted paying assistants to transcribe recordings. Once Scelsi supervised revisions, however, there was little intended room for performers to interpret works. Then the half-tone limits of piano keys moved him towards woodwinds, strings, human voice and electronic keyboards as vehicles for realizing micro-tonality. By 1959, Scelsi arrived at his mature musical system. The third phase of the 1960’s extended this system to orchestras, choruses, and a variety of chamber ensembles. This was the decade when Darmstadt recognized that a great composer had been quietly at work. Among Mode’s discs, the best entry point is “Music for High Winds”. Clarinetist Carol Robinson worked intensively with Scelsi during the 1980’s. Her impressive disc gives us the Scelsi parallel of Pears singing Britten. Then I would turn to Toronto pianist Stephen Clarke’s performance of Action Music (1955), a piece that synthesizes what Scelsi achieved for the piano. “Orchestral Works” stretches, literally, what can be done with power of the big instrumental beast that we’ve inherited from the nineteenth century Romantic tradition. It also includes striking samplings of Scelsi’s writing for voice. The solo clarinet version of Three Latin Prayers (1970) on “High Winds” announces phase four of Scelsi’s compositions, reworking tonality into his three-dimensional system. The clarinet sounds classically gorgeous and yet unfamiliar, as does the stately but varying tempo. Given the exemplary performances of Scelsi’s music in the four Mode discs at hand, let’s hope for future volumes dedicated to the composer’s final endeavours.

— Phil Ehrensaft, WholeNote, February 2006

Giacinto Scelsi

The Orchestral Works 1

Hymnos; Hurqualia; Konx-Om-Pax; Canti del Capricorno (selections).

Pauline Vaillancourt (soprano); Douglas Ahlstedt (tenor); The Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic and Concert Choir, Juan Pablo Izquierdo (cond.).

Mode 95

This is glorious Scelsi — a must-have item for Scelsi fans, and the perfect disc to make converts out of skeptics and innocents. I take my Scelsi appreciation seriously yet cautiously: This is a disc I play when everyone else is out of the house.

Initially I was wary of the disc’s order. Selections from Scelsi’s intimate song cycle Canti del Capricorno (for voice alone and sometimes voice with instruments) are scattered between three big orchestral works, Hymnos, Hurqualia, and Konx-Om-Pax. But the short and delicate songs are refreshing after the larger and more violent pieces. Pauline Vaillancourt and Douglas Ahlstedt give us numbers 1, 2, 18, 14, 15 and 19. We hear growls, nasal sounds and sometimes one singer must produce two vocal sounds at once. Canti del Capricorno is a rich cycle to draw upon, its primal and exotic qualities definitely more comprehensible in small doses. Vaillancourt has recorded another selection (numbers 1, 3, 5, 8, 12, 13, 16, 17 and 18) on the obscure Allegro-distributed Société Nouvelle d’enregistrement (SNE 571) along with selections from Georges Aperghis’ Récitations. (My Aperghis rave will have to wait until another time.)

Scelsi’s orchestral works build intense textures from very few pitches. Some movements (or sections of movements) focus on one single pitch played by different instruments in different octaves and colored with accents, microtones and extended techniques. In these three works Scelsi also uses long pedal tones, prominent percussion, and groups of amplified instruments. Every passing beat is a laboratory of orchestration: We may hear two horns playing a D with an oboe playing the same D an octave higher, and suddenly they will fade away and reveal muted violas and cellos playing the same notes. It’s all very miraculous and entrancing, and has no precedent in Western music.

From the single pitch that opens Hymnos (1963), Scelsi creates the illusion of overtones and notes that are just not there. Scored for organ and two antiphonal orchestras (the players in one standard orchestra divided into two groups that face each other onstage), the work is in arch form with a trance-like central section. Theouter sections move slowly, as if Scelsi were describing the motion of planets.

Hurqualia (1960), subtitled “A Different Realm,” is unexpectedly vibrant and active. The pensive opening is shattered by percussion and aggressive repeated notes, including a propulsive minor-third gesture not unlike that in Ride of the Valkyries. There are three groups of amplified instruments; one includes a musical saw, andanother playing in unison (oboe, English horn and E-flat clarinet) sounds particularly non-Western. I confess to using the 1990 Accord (201 692, a three-disc set of Scelsi’s complete works for orchestra and chorus with orchestra) to test-drive headphones and speakers, because Hurqualia has such a rich variety of colors andtimbres.

Most all of Scelsi’s titles are strange: Konx-Om-Pax (1968) links the word “peace” in Assyrian, Sanskrit and Latin. Its subtitle is “Three Aspects of Sound as the first movement of the Immovable; as Creative Force; as the syllable OOm1.” The work opens quietly with a delicate harp texture that has been captured very well here.The short second movement exposes blinding power, and a chorus is introduced in the finale — waves and valleys of sustained single pitches become dissonant chords.

The Accord set mentioned above is a cornerstone of the Scelsi fan’s collection. No two recordings of Scelsi’s orchestral music sound the same. This is a boon for the Scelsi lover who scoops up every recording, but it points out a flaw in Scelsi’s largest scores. The notation often fails at providing complete and incontrovertibleinstructions as to how instruments in large ensembles should be balanced. I base my remarks on seeing the Quattro Pezzi (su una nota sola) (1959) in the Koussevitsky Collection at the Boston Public Library. (That Koussevitsky had a Scelsi score in his possession boggles the mind!) In the denser textures, every instrument has its own dynamics, different from all the others. Almost every note has a dynamic, and sometimes one note ends with a decrescendo and the next begins with a crescendo; it’s not clear from what dynamic the second note should start. Conductors usually solve these problems themselves, but sometimes the publisher distributes a more completely edited score (a page from the Quattro Pezzi appears in the catalog put out by Scelsi’s publisher Salabert, and unclear dynamics are evident).

This is the second volume in Mode’s ongoing Scelsi series, promisingly titled “The Orchestral Works I,” and it makes a perfect introduction to the composer. The orchestral music is much grander and mellower than in the Accord set, and the combination of miniature vocal works and enormous orchestral ones makes very clear Scelsi’s non-Western interests and preoccupations. Juan Pablo Izquierdo commands the Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic with a greater evenness and zest than I hear in his disc of Xenakis and Varèse (Mode 58), and I can’t wait for more. In truth, it’s easier to listen to Scelsi than to describe his music. I recommend this disc wholeheartedly.

— Grant C. Covell, La Folia online review, August 2002

(lafolia.com/an-assorted-ramble/)

Giacinto Scelsi

The Orchestral Works Vol.1

Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic

Juan-Pablo Izquierdo

Mode 95

Since, as Harry Halbreich pointed out, the twentieth century is now “unthinkable without Scelsi”, it’s perhaps surprising that his orchestral works have until now only been recorded once in their entirety, in 1988, by the chorus and orchestra of Polish Radio and TV in Krakow conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach. Though it’s most welcome that Mode has now launched its own Scelsi series, I wonder if Izquierdo and the Carnegie Mellon Phil wouldn’t have been better off going away to summer camp to rehearse before recording the complete orchestral works on one double-CD, rather than filling out this disc with the “Canti del Capricorno” (which perhaps ought to be released separately in their entirety). These songs, written between 1962 and 1972, with their invented phonetic language and occasional quasi-ethnic accompanying percussion, have to my mind always seemed slight, even superficial, in comparison with the majestic, earth-shattering orchestral music Scelsi was writing at the same time: “Hurqualia” (1960), “Hymnos” (1963) and “Konx-Om-Pax” (1968) for large orchestra (augmented by organ on “Hymnos” and chorus on “Konx”) take their place alongside the major orchestral works of the decade by the likes of Ligeti, Xenakis, Penderecki and Zimmermann. “Hurqualia” is, by Scelsi’s standards, pretty vicious: his characteristic exploration of single pitches through timbral inflection and occasional migration to adjacent microtonal neighbors becomes a screaming, smearing, seething mass of lines, accompanied by some thoroughly cathartic blasts of percussion worthy of Varèse. “Hymnos”, as one might expect, is more cathedral-like, organ and orchestra combining to create the fabulous illusion of spectral choirs in the sky above, while “Konx-Om-Pax” (I agree with Riccardo Schulz’s description of it as “Scelsi’s crowning achievement”) should be on every composer’s work desk along with Stravinsky’s “Sacre”, Debussy’s “Jeux” (and a handful of other pieces) as an example of truly spectacular orchestration. Though the details of Izquierdo’s reading are perhaps clearer than the earlier Wyttenbach recording, there’s something about the acoustic of that Polish church (Saint Catherine’s in Krakow) that better lends itself to the great sonorous landscapes of Scelsi’s orchestral writing, where both instruments and performing space must combine to form an immense – and truly awesome – meta-instrument. There are some significant differences in terms of tempi: Wyttenbach takes 7’26” to get through “Konx”‘s first movement, while Izquierdo nails it in 5’41”! Wyttenbach’s last movement is all over in 8’39”, while Izquierdo drags his out to 9’59”. This new disc sounds more “Romantic” as a result – remember Halbreich also claimed that this is the music Bruckner would be writing were he alive today – perhaps Wyttenbach, as an ultra-modern avant-garde composer himself, was less out to stress the music’s spiritual breadth and more concerned with its tiny spectral details (shades of what they used to say about Boulez the conductor?). In any case, after “Konx” dies away, anything, especially the tiny “Canto No. 19” comes across as an irrelevant afterthought. That said, I’m looking forward to Volume 2 enormously.

— Dan Warburton, www.paristransatlantic.com/,

April 2001

SCELSI: Orchestral Works I

Carnegie Mellon Philharmon and Choir; Juan Pablo Izquierdo, conductor

Mode 95

Another lower case CD label doing yeoman service for contemporary music, mode issues its first volume of orchestral works by Giancinto Scelsi (pronounced Shell-see), a favorite of S.F. Symphony’s Michael Tilson Thomas. MTT tells wonderful stories about the late eccentric Italian, but playing his music is the greatest compliment, since records reproduce only a fraction of the visceral excitement of a live performance. Still, this disc contains vivid readings, in excellent sound, of “Hymnos,” “Hurqualia” and the piece MTT played last season, “Konx-Om-Pax.” The best way to describe Scelsi’s large scale works is to think of a juggernaut, rolling down a steep hill, getting louder, more insistent, and yes, crushing everything in its way. I love this music.

— Stephanie von Buchau, The Tribune, Oakland CA, 21 February 2001