Cage Edition 29–The Piano Works 6

Martine Joste, piano

Seven Haiku (1952)

1. Haiku I (0:17)

2. Haiku II (0:19)

3. Haiku III (0:17)

4. Haiku IV (0:16)

5. Haiku V (0:17)

6. Haiku VI (0:16)

7. Haiku VII (0:15)

Music of Changes (1951)

8. Music of Changes I (4:04)

9. Music of Changes II (18:36)

10. Music of Changes III (10:02)

11. Music of Changes IV (10:59)

Suite for Toy Piano (1948)

12. I (1:22)

13. II (1:33)

14. III (1:22)

15. IV (1:34)

16. V (1:03)

This disc collects 3 early piano works of John Cage, including his classic work for toy piano and early works composed using chance.

Music of Changes is a seminal piece in 20th century composition because it is the first work to be fully composed using chance operations. The title makes reference to the ancient Confucian book the I-Ching which, together with lectures by the Japanese Zen master Suzuki, introduced Cage to the concepts of chance. The title also makes reference to Cage’s change in musical direction with this work.

Cage prepared charts of squares which indicated numbers for tempo, dynamics, sounds, duration, rests and overlapping of material. He then used chance operations based on these numbers to compose a piece – devoid of personal choice and influences – which was then conventionally notated.

The element of noise is also introduced into the composition, with indications for sound to be made by closing the piano lid, pedal noise, playing inside the piano, knocking under the keyboard, etc.

The incredibly complex score includes 80 pages of instructions/directions written with the help of the pianist David Tudor, who premiered it.

The SUITE FOR TOY PIANO is among Cage’s infamous works. Composed in 1948 for the Merce Cunningham dance “Diversions”, it was premiered by Cage at Black Mountain College. Cage creates a magical piece composed around the limited resources of the toy piano.

7 HAIKU (1952) continues Cage’s influence from Asian culture and philosphy. Here the brief movements are structured around the Haiku form, each movement consisting of three structural bars in a length relation of 5-7-5.

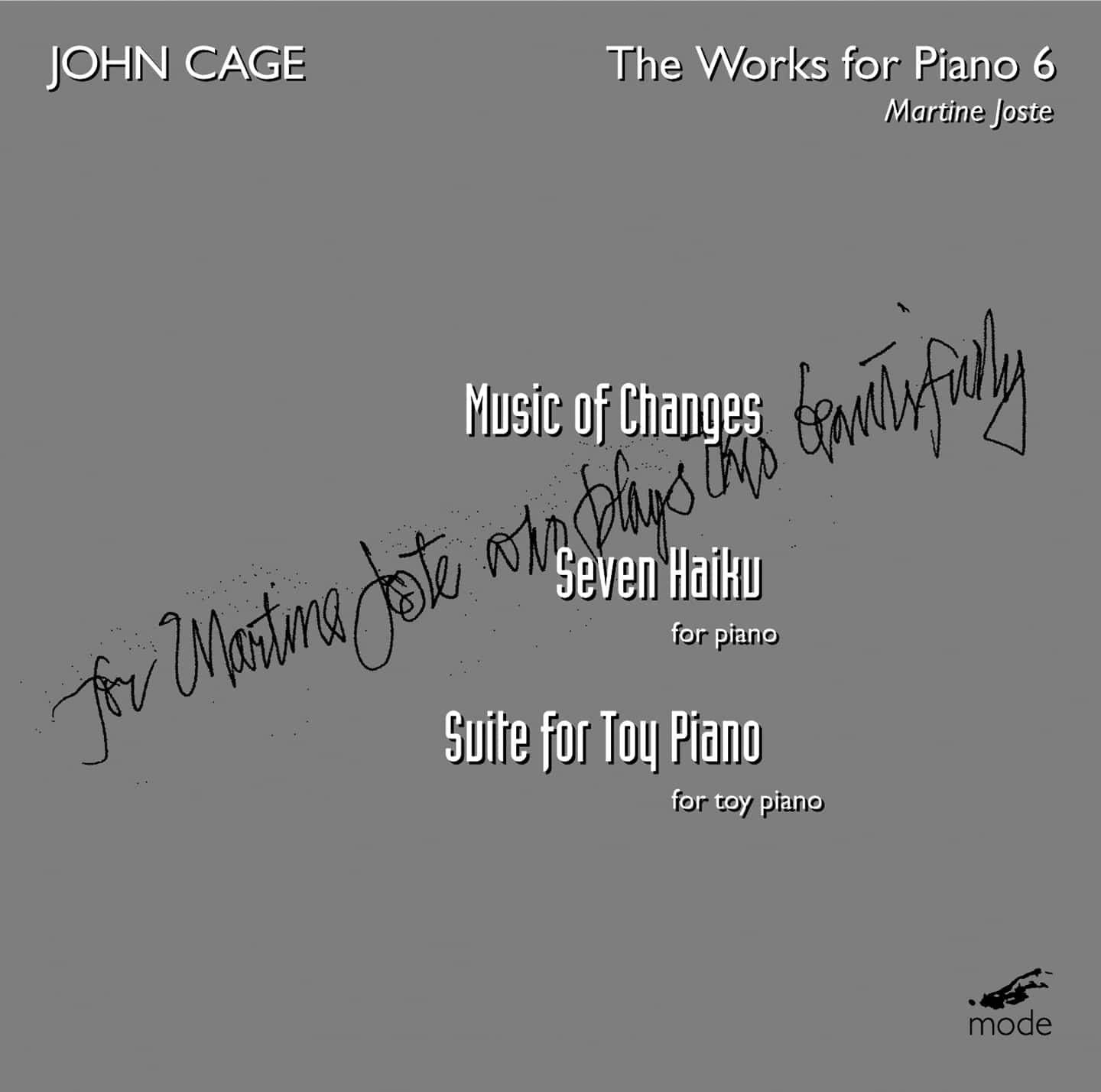

French pianist Martine Joste is a new music specialist with a tradition of playing Cage’s works. Cage wrote Two6 for Martine and the violinist Ami Flammer, which they premiered and subsequently recorded on Mode 44.

Liner notes by noted French writer Daniel Charles.

Reviews

John Cage

The Piano Works 6

Music of Changes (1951); Seven Haiku (1952); Suite for Toy Piano (1948).

Martine Joste (piano).

Mode 147

“The Complete John Cage Edition, Volume 29.”

Compared with:John CAGE: Music of Changes (1951). David Tudor (piano). hat[now]ART 133. Rec. Nov. 25, 1956.

“Grete Sultan: The Legacy, Vol. I.” John CAGE: Music of Changes (1951): Book I only. Grete Sultan (piano). Labor Records LAB 7037. Rec. 1974.

John CAGE: Music of Changes (1951). Herbert Henck (piano). Wergo 60099-50. Rec. Mar. / Apr. 1982.

“John Cage: Complete Piano Music Vol. 3.” John CAGE: Music of Changes (1951). Steffen Schleiermacher (piano). Musikproduktion Dabringhaus und Grimm MDG 613 0786-2. Rec. Oct. 24-27, 1997.

John CAGE: Music of Changes (1951). Joseph Kubera (piano). Lovely Music LCD 2053. Rec. 1998.

Despite the recording’s limitations, Music of Changes’ dedicatee performs with an aggressive vitality. Tudor had to have been reminded of Boulez’s Second and Artaud’s “Theatre of Violence.” Understandably, less resonance and aftereffects survive from WDR’s analogue tapes. (hatART CD 6181 offers Tudor at Cage’s Music for Piano No 52-56 taped the same day.) Some notes are inaudible, e.g., the first A-B grace notes and the third measure’s descending triplets. I wonder whether Tudor’s score differs from what Peters published in 1961. In 1978, New World Records released an LP, NW 214, with Tudor’s 1953 taping of III and IV.

Undoubtedly the best available recording (Tudor and Henck are O/P, Kubera and Schleiermacher fatally flawed), the aptly impetuous Joste follows Cage’s tempos, offering a front-row seat from which to share the risks. Chords punch, silences are pure. The pianist radiates the necessary heat. Mode’s recording ably captures the entirety, including the music’s interior sounds. Wisely programmed, balancing the studious and silly Cage, Joste permits other works at Music of Changes’ periphery. With their silences and nimble gestures, the Seven Haiku, none longer than 19 seconds, are like any Webernian splatter, though Cage will permit a Debussian flourish or a droplet of tonality. (Seven Haiku reused Music of Changes’ charts.) The closely recorded Suite for Toy Piano sparkles, a fitting chaser to Music of Changes’ density.

A surprising but appropriate sequencing, Labor precedes Music of Changes with Schoenberg’s Op. 33a. As I progresses – the only book offered – Sultan pays less and less heed to Cage’s tempos, isolating every gesture and chord with unnecessary air. It’s bizarre that someone so well acquainted with Cage (the 1974 Études Australes were written for her) would take such profoundly wrong liberties. Schoenberg’s Op. 23, Cage’s 1944 The Perilous Night, several Debussy Book II Études, and The Goldberg Variations complete this double-CD set.

Pronounced attacks characterize Henck’s calisthenic I, yet II – IV disappoint. The unexpectedly pinched environment indicates a different recording session. Wergo caught delicate after-effects, pizzicato and knocking, but Henck’s high voltage in I doesn’t persist. Still working today, Henck understands this music’s context better than anyone else. ECM ought to rerecord him.

Schleiermacher hews to a tempo almost 23% slower than Tudor and 25% slower than Joste, his intent being to shed light on denser passages. It’s a poor strategy. Though more frolicsome than others, his gambit yields no revelations. The remotely placed piano’s acoustic shines artificially. Overtones and sustained pitches are muddled.

Kubera applies a strong dose of traditional musicality to newfound melodic traces, exposing some unintended dominant-tonic motion. A meek resonance matches the incorrect postmodern aesthetic. The four books slur together without pause.

—Grant Chu Covell, “1951 and Cage’s Music of Changes”,

www.lafolia.com, April 2006

John Cage

The Piano Works 6

Martine Joste (piano)

Mode 147

Artistic Quality – 8

Sound Qualiy – 9

In its size, scope, and difficulty, John Cage’s 1951 Music of Changes might be looked upon as a response to Pierre Boulez’s 1948 Second Piano Sonata. The results of Cage’s extraordinary pre-compositional rigor demand split-second changes in register, voicing, texture, varied pedalings, and too many dynamic levels for one player to absorb. Only the most dedicated and accomplished new-music pianists are able to realize Cage’s exacting notation with both accuracy and love. Martine Joste is such an artist. The mesmerizing control and authority she brings to each of the work’s four books is borne out of long familiarity and digestion, and it comes as no surprise that Cage himself praised her performances.

If you want to split hairs, the closer miking and deeper resonance of Joseph Kubera’s recording on Lovely Music yields clearer distinctions between Cage’s micromanaged pedal markings and crisper articulation of rapid arpeggiated gestures. However, Mode’s engineering bests MDG’s Cage Edition with Steffen Schleiermacher for presence and impact.

Joste brackets Music of Changes with two of Cage’s simplest keyboard works: the Webern-esque Seven Haiku (gorgeously nuanced and spaced) and the Suite for Toy Piano (too dryly recorded, and a bit sluggish and lacking in whimsy compared to Margaret Leng Tan’s lively interpretations for several labels). Daniel Charles’ booklet notes preach to the converted and hold more value for scholars, philosophers, musicologists, and serious Cage specialists than for general listeners.

— Jed Distler, Classics Today, 2006