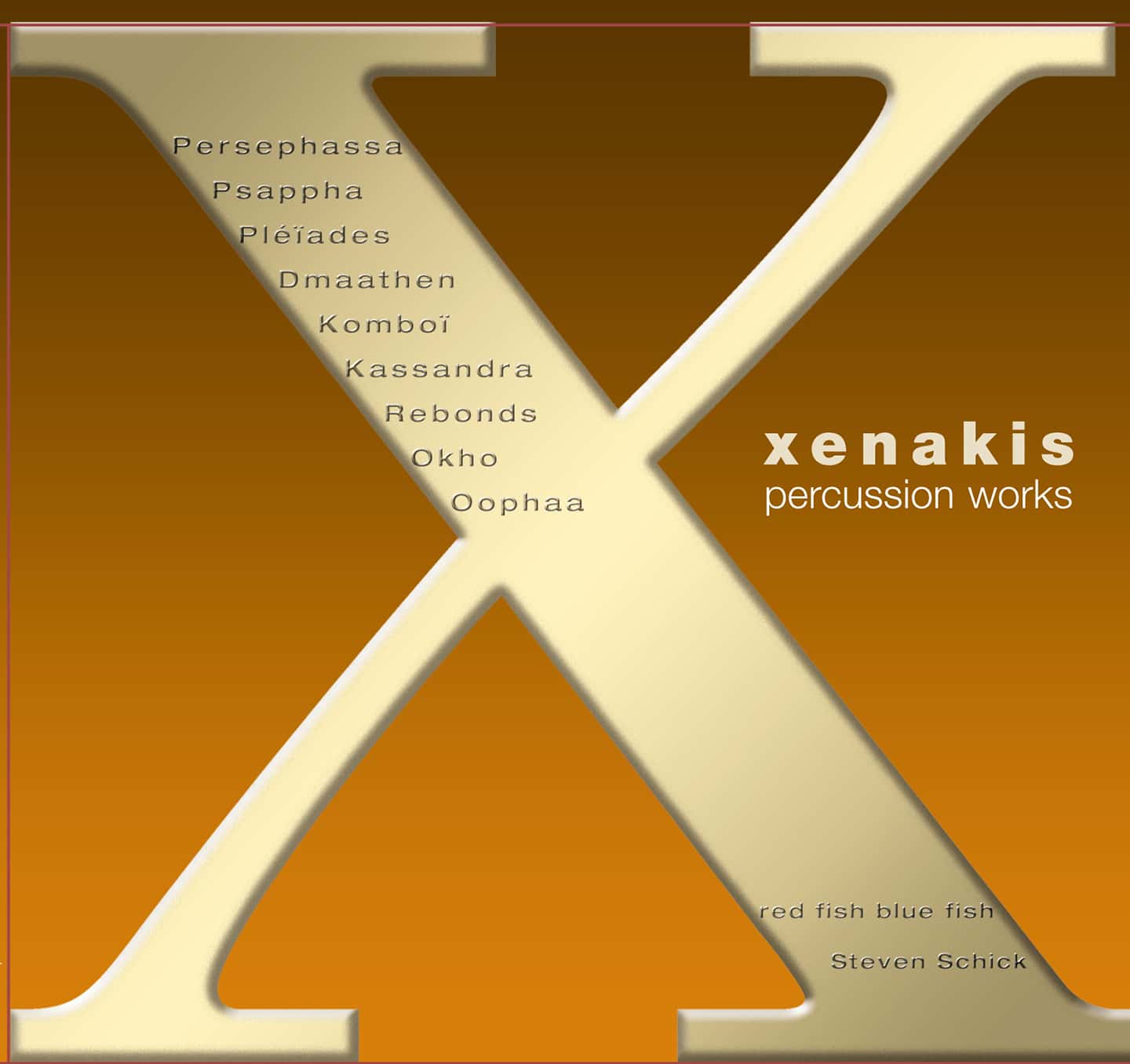

Xenakis Edition 7 - Complete Percussion Works

DISC 1

Persephassa (1969) (28:37)

percussion sextet

Percussion Ensemble red fish blue fish: Patti Cudd, Aiyun Huang,

Terry Longshore, Brett Reed, David Shively, Vanessa Tomlinson

Psappha (1975) (13:59)

Percussion Solo

Steven Schick, percussion

Dmaathen (1977) (10:57)

Percussion Duo

Jacqueline Leclair, oboe

Steven Schick, percussion

DISC 2

Pléïades (1978)

percussion sextet

Percussion Ensemble red fish blue fish

Mélanges (8:52)

Gustavo Aguilar, Rob Esler, Ross Karre, Don Nichols, Morris

Palter, Lisa Tolentino

Claviers (10:36)

Métaux (13:31)

Peaux (11:55)

Patti Cudd, Terry Longshore, Ivan Manzanilla, Brett Reed,

David Shively, Vanessa Tomlinson

Komboï (1981) (20:02)

Percussion Duo

Aiyun Huang, percussion

Shannon Wettstein, harpsichord

DISC 3

Kassandra (1987) (20:48)

Percussion Duo

Philip Larson, voice

Steven Schick, percussion

Okho (1989) (13:14)

for three djembes

percussion sextet

Percussion Ensemble red fish blue fish: Terry Longshore, Brett Reed,

David Shively

Oophaa (1989) (11:49)

Percussion Duo

John Mark Harris, harpsichord

Greg Stuart, percussion

Rebonds (1989)

Percussion Solo

B (5:24)

A (6:09)

Steven Schick, percussion

The first complete set of Xenakis’ percussion ensemble, percussion duos, and solo percussion works. As Steven Schick states in his comprehensive essay accompanying this set, Xenakis was the “progenitor of modern percussion music.” Of course Iannis Xenakis did not create percussion music, his first major contribution to the percussion repertory came more than three decades after the American percussion revolution of Edgard Varèse, John Cage and Henry Cowell. But as Jorge Luis Borges said of Kafka, he was so important that he influenced even those who came before him. Indeed, our early 21st century ear for percussion music has been so tuned by the music of Xenakis that we cannot fail to understand the first cacophonous noise constructions of Varèse’s Ionisation (1931) and Cage’s First Construction (1939) through the retro-lens of the raw and terrifying noises in Xenakis’ percussion works.

24-bit audiophile recordings.

red fish blue fish is the resident percussion ensemble of the University of California, San Diego. The group functions as a laboratory for the development of new percussion techniques and music, and has toured widely. Its concerts have included Lincoln Center, as a part of two Bang on a Can marathon concerts, the Agora Festival (Paris), the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Green Umbrella Series, the Centro des Bellas Artes in Mexico City, and the Percussive Arts Society International Convention. In addition the group offers a regular series at the University of California, San Diego.

For the past 30 years, Steven Schick has championed contemporary percussion music as a performer and teacher. He studied at the University of Iowa and received the Soloists Diploma from the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, Germany. Schick has commissioned and premiered more than 100 new works for percussion and has performed these pieces on major concert series such as Lincoln Center’s Great Performers and the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Green Umbrella concerts as well as in international festivals including Warsaw Autumn, BBC Proms, Jerusalem Festival, Holland Festival, Stockholm International Percussion Event and the Budapest Spring Festival among many others. Schick is the founder and Artistic Director of the percussion group, red fish blue fish.

DEFECTIVE MODE DISCS MAY BE EXCHANGED

Unfortunately, the first pressing of the recent XENAKIS: Percussion Music set (mode 171/3) had some bad edits on disc two during Pléïades. If you have purchased this set, and the disc two serial number on the label does not read “mode 172R”, then you have the early pressing with the problem edits. Mode will exchange these discs free of charge. Please return only the original disc two (mode 172) to us and we will send you the new, improved version in exchange.

The second pressing of Chaya CZERNOWIN’s “Afatsim” (mode 77) developed a static burst during Track 4 “Dam Sheon Hachol” (at about 23:06). The good thing is that very few of these were actually shipped before the problem was discovered. Again, if you have a defective disc, please return it to us and we will send you a replacement.

Reviews

Iannis Xenakis

Percussion Works

Red Fish Blue Fish/Steven Schick

Mode 171/173

Steven Schick’s recent book The Percussionist’s Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams is an extraordinary example of musical writing that comes from inside the action. Now comes the action itself, almost tangibly felt in the sound that pats, purrs and wallops out of a three-record set of percussion music by Xenakis (Mode 171/73). Included are the two solo pieces, four duos (Xenakis wrote twice for the unexpected coupling of harpsichord and percussion) and three works for percussion ensemble. Schick plays the solos and takes part in two of the duos (not those with harpsichord, which he relinquishes to colleagues); the ensemble pieces are performed by the group he has trained, red fish blue fish, playing without him.

One surprise emerging from the collection is that Xenakis turned to percussion only during quite concentrated periods. After the lone Persephassa, written in 1969 for Les Percussions de Strasbourg to release over the ruins of Persepolis (during the brief time when the Shah’s government financed a festival there), the composer produced four varied percussion works between 1975 and 1981 (the solo piece Psappha, another sextet for the Strasbourgeois – Pléïades – and two duos) and a further four in the late eighties (including Rebonds for solo drummer and Okho for three). Schick, in his excellent notes, observes a move from colourful to homogeneous set-ups, and yet even when Xenakis calls for a great variety of instruments, as he does in Persephassa, the sound is uniform for long stretches. Perhaps it has to be, given that, as Schick also observes, Xenakis’s percussion music reawakens the ritual use of such instruments, a use that depends on pattern repetition (a constant here, from Persephassa onwards) and on signalling (which requires there to be distinctive timbre characters that can be identified as callers and responders), as also on strong pulsation. The solo pieces have all these qualities as much as the sextets do. In Psappha, variegated instruments seem to be signalling to each other, moving the music on towards the final home-run for pounding drums and clanging bells. Rebonds is more a declamation.

Schick is superb in both these pieces. His sense of timing is acute, whether expressed in phrasing or in how, unforgettably, Rebonds A gradually runs out of steam. It is the shapeliness of sound and rhythm – the presence of the body in the slap of a hand on a drum (something Schick’s students emulate in Okho) or the flow of a gesture – that makes these performances almost visual in their effect. Schick is also excellent in the extraordinary Dmaathen, where he has to encourage, support and applaud the virtuoso strangeness of the oboe part – strikingly enunciated by Jacqueline Leclair – which is made of multiphonics, a harmonic clean as flute tone and elemental (perhaps only elementary) tunes.

— Paul Griffiths, Words and Music (online), July 2007

Iannis Xenakis

Xenakis Percussion Works

Steven Schick, Red Fish Blue Fish

Mode 171/173

Iannis Xenakis’s music is elemental, antiRomantic, architectural, ritualistic, dispassionate. It is also deeply poetic, its emotional power vast, as the nine works recorded here testify. For ensemble, there’s the raw, aggressive drama of Persephassa (1969) and the static, beautiful Pléïades (1978). For solo percussionist, there are the complex, thrillingly technical challenges of Psappha (1975) and Rebonds (1989). Perhaps most impressive of all, there’s the ritual drama of Kassandra (1987), where the voice of Philip Larson conveys an increasingly furious frustration. All is driven by the energy and musicianship of Steven Schick, who plays the solo pieces and directs the six percussionists of Red Fish Blue Fish.

— Stephen Pettitt, The Sunday Times, 11 February 2007

Iannis Xenakis

Percussion Works

Red Fish Blue Fish/Steven Schick

Mode 171/173

PERFORMANCE

SOUND

Howard Goldstein is amazed by a revelatory Xenakis set

Xenakis, of all the 20th century’s radical rethinkers of musical parameters, managed to keep the strongest link with music’s traditional ritualistic associations. This is perhaps most obvious in his percussion music, collected here in stunningly played and recorded performances by Red Fish Blue Fish, the resident percussion ensemble at the University of California, San Diego, directed by Steven Schick.

Persephassa (1969) marked the beginning of the composer’s exploration of music’s temporal dimensions with the same scientifically rigorous yet musically gripping approaches previously applied to pitch and form. Here six players encircle the audience; even in two-channel, Mode’s engineers give us enough spatial cues to appreciate the final section’s accelerating vortex of rhythmic layers (realised here with some discreet overdubbing) and sliding whistles (human and inhuman at the same time).

Every performance of Psappha (1975) is unique, given the freedom of choice allowed the soloist with regards to instrumentation. Schick’s evenness of touch and mastery of pacing make it hard to believe that one person is playing these absurdly complex interlocking timbral and rhythmic patterns, reminiscent of a one man gamelan orchestra.

Gamelan-like structures and sonorities also permeate Pleiades (1978), where the harrowing sound of ‘Sixxen’, metallic plates in sets of 19, microtonally tuned to each other, produce a shimmering glaze of overtones, at times almost producing the glissandos so important to Xenakis’s theories of the relationship between pitch and time. Glissandos also abound in the vocal part of Kassandra (1987), whose prophecies are dramatically intoned in falsetto by baritone Steven Larson, and punctuated by the discordant strum of the psaltery. Here Xenakis’s ritualistic side finds its most natural outlet in one of his frequent encounters with ancient Greek culture, in this case the Oresteia. Texts and translations would have been nice here; the general omission of title translations, instrumentation lists and other ‘nuts and bolts’ information is the only blot on this otherwise exemplary issue.

— Howard Goldstein, BBC Music Magazine, February 2007

Iannis Xenakis

Xenakis Percussion Works

Mode 171/173

A few years ago the music of Iannis Xenakis suddenly became radically chic, thanks to the well-intentioned efforts of the likes of DJ Spooky and other Deleuze-toting hipsters. More recently a younger generation of fun lovin’ noiseniks have been singing the praises of pieces like Bohor and Persepolis as if they were the latest offerings from Merzbow, Prurient and Sickness. But this attraction to the visceral, violent side of the composer only addresses half of the Xenakis enigma, as percussionist Steven Schick makes clear in his informative and eminently readable liner notes to this 3-CD set. There was also Xenakis the mathematician, master of the impenetrable FORTRAN, creator of UPIC. Any of you out there read Formalized Music (me neither – I got as far as page 100)? It’s easy to thrill at the swarming glissandi of Metastasis or succumb to the apocalyptic intensity of Kraanerg, but without the serious theoretical underpinning, those extraordinary works wouldn’t sound the way they do. And without the background and years of study, none of the distortion pedal abusing wolf-eyed teens currently tearing round the alt.music racetrack will ever get remotely close.

As Schick points out, the striking contrast between the brutally impersonal world of advanced mathematics and symbolic logic and the spine-tingling raw emotion is no more evident than in the body of works Xenakis wrote for percussion (with or without added instruments): Persephassa (1969), Psappha (1976), Dmaathen (1976), Pléïades (1979), Komboï (1981), Kassandra (1987), Rebonds (1988) and Oophaa and Okho (1989). No recording could possibly capture the sheer power of this pieces in performance – I caught Pléïades in Paris shortly after its premiere, and can still remember the utterly devastating experience of being surrounded in the Auditorium of Université Paris II Assas by six sets of sixxen (specially created instruments consisting of tuned metal plates) – but until you get a chance to see and feel it in the flesh, you could do no better than get hold of these excellent recordings by Schick and the red fish blue fish percussion ensemble (lowercase intended.. Dr Seuss plays Xenakis, dig it).

Schick is also joined by Philip Lanson (baritone and psaltery, on Kassandra), Jacqueline Leclair (oboe, on Dmaathen in the most thrilling double-reed / percussion battle to come my way since Kyle Bruckmann went the distance with Weasel Walter on his Musica Genera album) and harpsichordists Shannon Wettstein (on Komboï) and John Mark Harris (Oophaa). Not all the pieces are as spectacular as the percussion ensemble pieces Persephassa and Pléïades – the rather plodding Okho once more raises the question as to whether the composer was losing his touch a little in his final years – but that’s one of the risks you take when you release a complete set of anything. This one’s worth the price of admission alone for the spectacular ending of Persephassa, in which Schick and his crew use multitracking to realise, for the first time on disc, the ferocious near-impossible complexity of the score’s final pages. I say near-impossible, because, as Aki Takahashi once wryly noted, “if Xenakis’s music is truly impossible, why are so many people playing it?”

— Dan Warburton, www.paristransatlantic.com/, January 2007

Iannis Xenakis

Xenakis Percussion Works

Mode 171/173

“It is not an exaggeration to say that for many contemporary percussionists, learning how to play has meant learning how to play the music of Iannis Xenakis,” declares percussion master Steve Schick in his introduction to this triple CD set of the great Greek composer’s complete percussion music. Ever since Xenakis’s friend and mentor Edgar Varèse scandalized a New York audience in 1933 with his percussion ensemble work Ionisation, the profile of the onetime subservient percussionist has risen. John Cage and Lou Harrison’s 1940s works stepped the percussion project up a gear; Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Zyklus (1959) gave percussionists a meaty one-off display piece. But no other composer defined a fresh syntax and potential-fuelled modus operandi for percussion music like Iannis Xenakis.

This set is much needed. In the Xenakis Primer I wrote for The Wire 259, I expressed doubts about his percussion works, but I now see that my quibbles were caused by recorded performances which sometimes haven’t made the grade, and which have suffered from dubious fidelity. Mode never deal in anything less than impeccable sound and, alongside Schick himself, the San Diego percussion ensemble Red Fish Blue Fish play with a devotion to detail and inner fire.

Writing for percussion is a daunting challenge for any composer. An authentic engagement with the character and DNA of percussion takes time to accomplish, and too many pieces deal in splashes of decorative colour or register as stiffly notated transcriptions of Buddy Rich solos. Xenakis sidestepped both issues by simply deciding they weren’t of significance to him.

The earliest work he wrote for persuccion was Persephassa in 1969 (could there be more perfect Xenakis title?), and already he was writing with certainty about how he wanted percussion to sound. Stretching out over a near 30 minute canvas, Persephassa is written for six percussionists, each of whom sits in what Xenakis defines as their own “sieve”. At the start of the work the sieves provide each player with their own rhythmic terrain, and allow Xenakis to create infinitesimal degrees of rhythmic displacement. The opening passage dances in your head with the force of dense polyrhythmic boulders plunging down a mountainside, each part proudly proclaiming its own independence while enigmatically jammed into the whole.

A key intrigue in all Xenakis’s percussion music in his strategic doublebacking between rhythm and pitch; here he incorporates swirling sirens and whistles into the flow. If the sirens might sound like they’re referencing Varèse, actually their feral microtonal inflections relate more to the trademark string glissandi of an early Xenakis orchestral work like Metastaseis.

Both his later percussion sextets, Pléïades (1978) and Okho (1989), were originally conceived for Les Percussions De Strasbourg and find Xenakis going ever deeper into the percussion zone. Pléïades splits the ensemble up into skins and keyboard percussion, and includes a section for the self-invented ‘sixxen’, a 19-note microtonal metal keyboard instrument designed to highlight the clashing harmonic overtones between notes. The overtones generate shimmering waves over the ensemble, and never have they been captured with greater clarity on CD, Okho adds the brittle tones of djembes – West African hand drums – to Xenakis’s palette.

By the time of Okho Xenakis’s contribution to the percussion repertoire was unassailable. The same year he also produced Rebonds, which has been recorded many times previously.

Familiarity makes it easy to take it for granted, but Schick’s performance is a reminder of its nuanced subtleties and power. Pitched drums are locked into a dialogue with chattering woodblocks. At the start, Xenakis provokes the two into a testy, dissonant irrational rhythmic relationship that sets up enough tension to power the music onwards through its ten minute duration.

An earlier solo piece, Psappha (1975), is more problematic, as Xenakis tosses percussionists the impossible challenge of playing up to 25 ‘hits’ a second at the climactic point. According to Schick, some players have concocted multiple-headed sticks to help them cope, but Xenakis’s aspirations for performers to stretch beyond the possible has historical precedent in Beethoven’s cello writing in his Grosse Fuge and the 20-fingered mutant hand presumably required to play some of Ives’s block chords on the piano. Schick quotes pianist and Xenakis specialist Aki Takahashi: “If Xenakis’s music were truly ‘impossible’, why (are) so many of us playing it?”

Xenakis continues to be a central figure because, like other 20th century ‘outsider’ such as Satie, Ives and Varèse, he dealt in material and not with idiom or style. The extraordinary falsetto vocal writing he devised for his voice/percussion duo piece Kassandra (1987) is unheralded and yet rooted in something deeply humane. Similarly, Dmaathen (1977) for oboe and percussion at first sound like curious, snake-charming music. Then mallet percussion and oboe refract their material through each other – gestures become elongated, and instrumental textures are obligated to buckle into obstreperous multiphonic screeching, so that macro meets micro. Two scores for harpsichord and percussion – Komboï (1981) and Oophaa (1989) – are fastidiously worked through so that their rhythmic and pitch qualities fuse to create a ‘third’ hybrid instrument. It’s a fitting analogy – harpsichord, that most ancient of Classical hardware, running up against Xenakis’s mind-expanding exploration of the possibilities of percussion.

— Philip Clark, The Wire, January 2007

Iannis Xenakis

Percussion Works

Mode 171/173

Much is made about the duality of Iannis Xenakis, and rightly so. There is the Turing-like savant who saw through the lead shield of FORTRAN and devised UPIC. And then there’s the mythologist with an Artaudian sense of cruelty. Xenakis reconciled these seemingly contrary facets by using objective processes to compose pieces seething with primordial power. This is why his music speaks to many listeners who otherwise have no use for composition, history, et al. Arguably, these aspects of the composer’s sensibility collide with the greatest force in his compositions for percussion, where the common starkness of numbers and ritual is unfiltered. Presented in chronological order, this 3-CD collection of Xenakis’ percussion works (a term that encompasses both pieces scored only for percussion and duets scored for percussion and another instrument) details how this starkness prevailed. Even though the titanic clashes between instruments on “Persehassa” (the earliest, written in ’69) were largely mitigated by the penning of “Pléïades”, the silence-punctuated ensembles, the languorous ripples and Reich-like pulse of keyboard-configured instruments and the gamelan-tinged phasing of sixxen (Xenakis’ pitched metallic invention) in the 1978 consensus-pick masterpiece retain the earlier piece’s demand for clarity. This demand is perhaps most stringently expressed in the duets with harpsichord, “Komboï” and “Oophaa,” composed in the early and late ’80s, respectively, where the material’s intense rhythmic drive is tempered by the dynamic restraints imposed by the harpsichord. There are numerous daunting challenges to present this body of work as a whole, which the project’s director, Steven Schick, meets in the only appropriate way – head-on. Whether he leading the red fish blue fish percussion ensemble or tackling the set’s two percussion solos and the duets with oboe and voice, Schick demonstrates a palpable understanding of Xenakis’ intents and purposes, a key reason why this is a monumental collection.

— Bill Shoemaker, Moment’s Notice, www.pointofdeparture.org, 2007