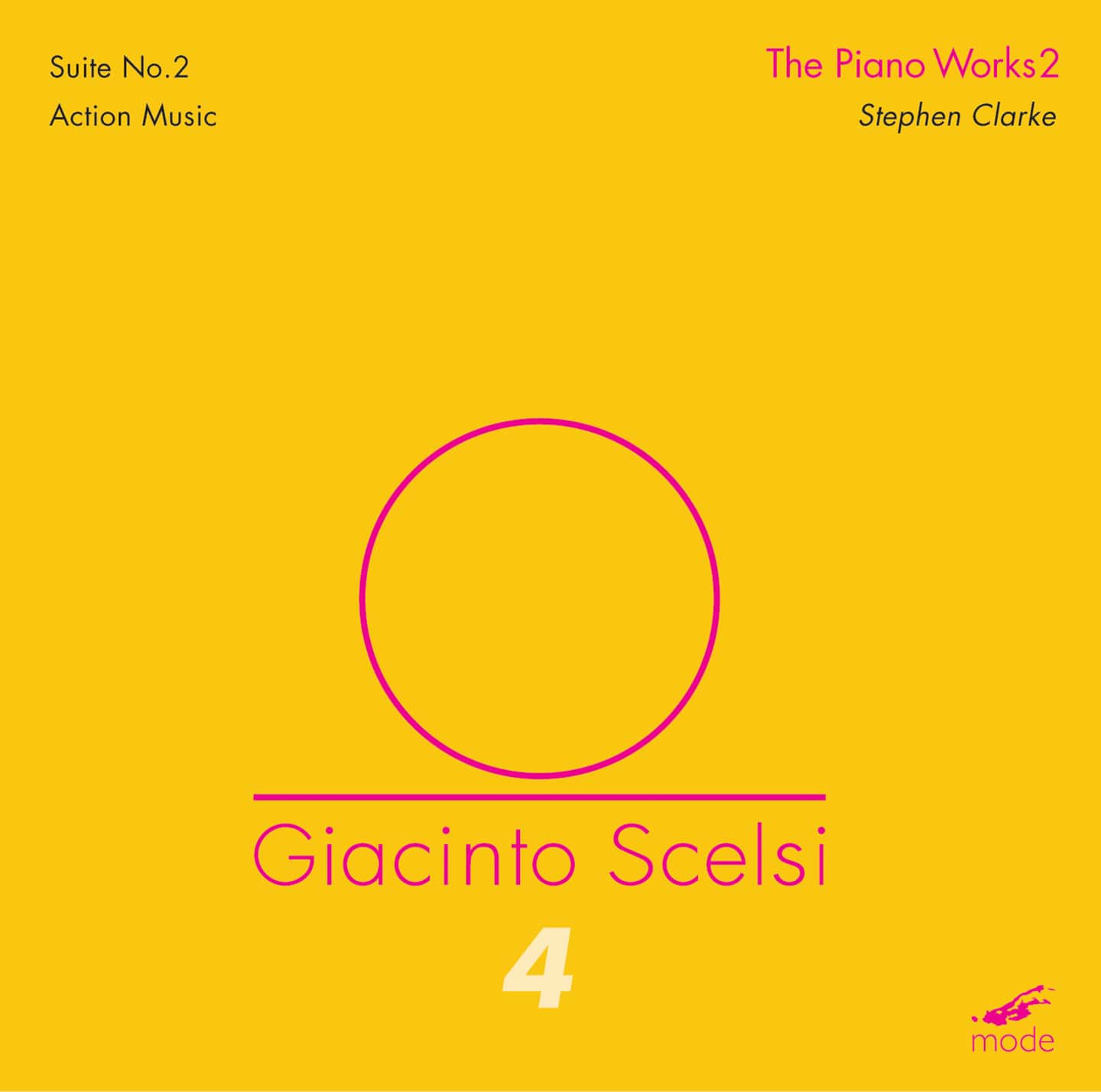

Scelsi Edition 4–The Piano Works 2

Stephen Clarke, piano

Suite No. 2 (1930)

1. Grandioso (3:33)

2. Appassionato (4:24)

3. Imperioso ed incisivo (4:50)

4. Drammatico (4:44)

5. Drammatico (3:29)

6. Sostenuto (4:16)

7. Incisivo (3:13)

8. Maestoso (3:54)

9. Imperioso (2:26)

10. Sostenuto (4:36)

11. Imperioso (2:07)

12. Molto mosso (5:12)

first recording

Action Music (1955)

13. Poco piu mosso, Veloce (2:07)

14. Iniziando e subito accelerando… (1:22)

15. Lento dolce (tutto col palmo della mano) (1:16)

16. Martellato (1:11)

17. Violento (2:00)

18. Brillante (1:48)

19. Pesante (1:39)

20. Veloce (1:46)

21. Con fuoco (1:52)

Mode’s Scelsi Edition continues with the second volume devoted to his piano works, consisting of two works from different periods in Scelsi’s oeuvre.

- The Suite No. 2 is one of the earliest of Scelsi’s published piano works.

- A highly virtuosic and expressive work, this Suite receives its first recording here.

- Written in 1955, Action Music is among Scelsi’s last piano works.

- Action Music was premiered by Geoffrey Douglas Madge in 1986 in Darmstadt.

- The title Action Music points to the high energy and physical and gestural elements of the music. The work’s vigorous character is underscored by predominantly fast tempi and directions for playing, including violento, con fuoco, martellato, fragroso (deafening!) and come percussione.

- In Action Music the performers are asked to play the piano in unusual ways by using their palms parallel to the keyboard, and employing fists and forearms to perform single pitches, chords, clusters and glissandi.

- One of Canada’s leading pianists, Stephen Clarke has performed as a soloist in festivals in Europe, Canada, and the U.S. He has worked with a number of ensembles and has performed as a soloist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the Composers’ Orchestra.

- This audiophile quality recording was made using high-resolution 96khz/24-bit technology.

Reviews

Scelsi Volume 1 – The Piano Works 1

Louise Bessette, piano

Mode 92

Scelsi Volume 2 – The Orchestral Works 1

The Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic & Concert Choir

Juan Pablo Izquierdo

Mode 95

Scelsi Volume 3 – Music For High Winds

Carol Robinson, Clara Novakova, Cathy Milliken

Mode 102

Scelsi Volume 4 – The Piano Works 2

Stephen Clarke, piano

Mode 143

Referring to Giacinto Scelsi (1905-1988) as Italy’s Charles Ives is both on and off the mark. Like Ives, Scelsi’s brilliantly radical and idiosyncratic music only gained recognition at a late stage in the composer’s life. Both were ultimate inner-driven composers. In other respects they are polar opposites. New England’s solidly bourgeois Ives studied music at Yale and became an insurance executive. Scelsi was an independently wealthy Count who trained in a very eighteenth-century way via private mentoring. After thriving as a virtuoso pianist, composer, poet and essayist in interwar Paris, Scelsi turned intensely private. While Ives drew inspiration from American vernacular music, Scelsi learned music and religion in India. He then created a deep hybrid of Asian and European musical structures. Three of the four phases of Scelsi’s compositional path, plus one shining selection from the final period, are represented to date in Mode’s important series of Scelsi recordings. Phase one (1930-43) involved Scriabin, futurism, atonality, and dodecaphony. The Piano Suite 2 (1930) on Volume 4 already presents an attention to overtones that would inspire Scelsi’s microtonal, “three-dimensional” music. Phase two begins with an extended nervous breakdown and Scelsi’s creation of a new musical system as a vehicle for self-healing. He focused on complex nuances that could be generated from a single note. Scelsi’s practice of Buddhist meditation and Yoga was integral to the attentiveness that attuned him to microtonal consequences of individual sounds. Beyond pitch and duration, this was music’s third dimension. Through 1956, Scelsi composed mainly for piano. Real-time composition was part and parcel of his new musical system. In the late 1940’s, Scelsi tape-recorded piano improvisations. His ample wealth permitted paying assistants to transcribe recordings. Once Scelsi supervised revisions, however, there was little intended room for performers to interpret works. Then the half-tone limits of piano keys moved him towards woodwinds, strings, human voice and electronic keyboards as vehicles for realizing micro-tonality. By 1959, Scelsi arrived at his mature musical system. The third phase of the 1960’s extended this system to orchestras, choruses, and a variety of chamber ensembles. This was the decade when Darmstadt recognized that a great composer had been quietly at work. Among Mode’s discs, the best entry point is “Music for High Winds”. Clarinetist Carol Robinson worked intensively with Scelsi during the 1980’s. Her impressive disc gives us the Scelsi parallel of Pears singing Britten. Then I would turn to Toronto pianist Stephen Clarke’s performance of Action Music (1955), a piece that synthesizes what Scelsi achieved for the piano. “Orchestral Works” stretches, literally, what can be done with power of the big instrumental beast that we’ve inherited from the nineteenth century Romantic tradition. It also includes striking samplings of Scelsi’s writing for voice. The solo clarinet version of Three Latin Prayers (1970) on “High Winds” announces phase four of Scelsi’s compositions, reworking tonality into his three-dimensional system. The clarinet sounds classically gorgeous and yet unfamiliar, as does the stately but varying tempo. Given the exemplary performances of Scelsi’s music in the four Mode discs at hand, let’s hope for future volumes dedicated to the composer’s final endeavours.

— Phil Ehrensaft, WholeNote, February 2006

Giacinto Scelsi

Volume 4: The Piano Works 2

Mode 143

Increased familiarity with Scelsi underscores his piano works’ strangeness. How could a composer who built entire movements from the slightest microtonal shifts write for the piano’s 88 fixed pitches? Whether you consider Scelsi’s keyboard compositions skillfully completed transcriptions or notated improvisations, many pianists find the Italian loner’s music attractive.

Mode has released Suite No. 2’s first recording. Written when the composer was 25, this work bonds Scriabinesque flourishes with dance-hall propulsion. The 12 varying movements foreshadow the composer’s alternating frenzied and plaintive tendencies, but with Rachmaninovian usages. In the 1940s, Scelsi suffered a mental breakdown and cured himself by continually playing single notes on a piano and focusing intently upon each decay. Action Music comes from the end of Scelsi’s creative days. Sounding like Antheil or Ornstein, the nine movements employ crashing clusters and vigorous chord splashes. Clarke digs in resolutely, emphasizing the pages’ mighty contrasts.

— Grant Chu Covell, La Folia online review, December 2005

Links

Also by these artists on Mode Records:

Giacinto Scelsi:

The Piano Works 1 (mode 92)

The Orchestral Works 1 (mode 95)

The Orchestral Works 2 (mode 176)

Music For High Winds (mode 102)

The Piano Works 3 (mode 159)

The Works for Double Bass (mode 188)

Stephen CLARKE (with Marc Sabat, violin):

Morton FELDMAN: Vol. 3: Complete Works for Violin and Piano-Sabat/Clarke Duo (mode 82/83, 2-CDs)

Christian WOLFF: Vol. 5: Complete Works for Violin and Piano

(mode 126)

Giacinto Scelsi Profile

Stephen Clarke Profile