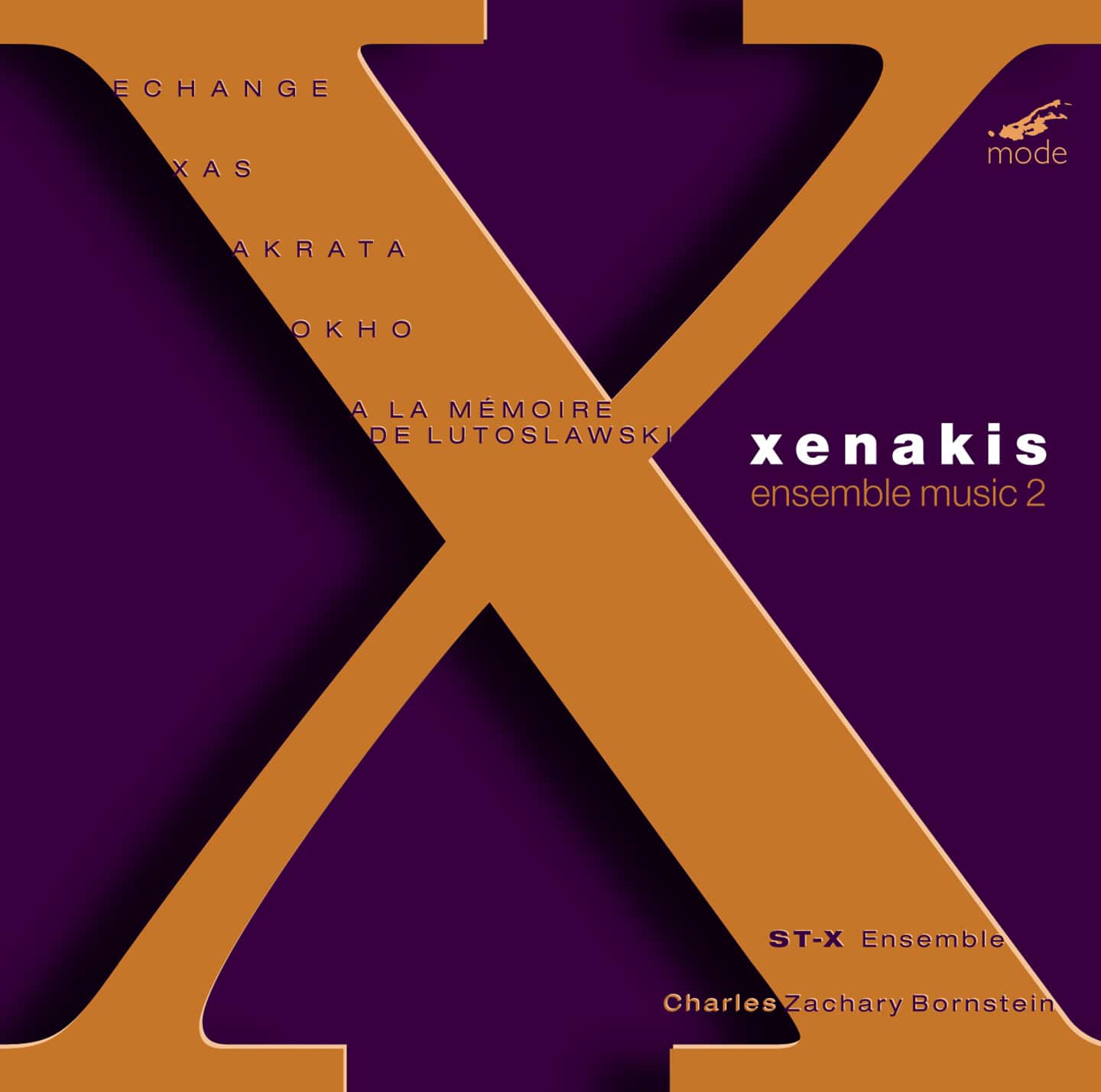

Xenakis Edition 2-Ensemble Music 2

ST-X Ensemble/Charles Zachary Bornstein

Échange (1989)

for bass-clarinet & ensemble.

Michael Lowenstern, bass-clarinet

Okho (1989)

for 3 djembes.

Xas (1987)

for saxophone quartet.

Akrata (1964-65)

for 8 winds & 8 brass.

(first time on CD)

A la Mémoire de Witold Lutoslawski (1994)

for 2 trumpets & 2 horns.

(first recording)

Recorded after performances at New York’s prestigious 92nd Street Y in 1996 with the participation of the composer,Ensemble Music 2 is the follow up to the initial, critically acclaimed and best selling volume of Xenakis’ Ensemble Workson Mode.

This disc contains the first recording of Xenakis’ memorial work A la Mémoire de Witold Lutoslawski,to the great Polish composer. A literal monument in sound, comprised of massive blocks of brass arranged as a dirge-likefanfare. Composed in 1994, it is the most recent work of Xenakis to be recorded.

Receiving its first CD recording here, Akrata is “classic” and seminal Xenakis. The work’s skittering, repeated notesand extreme changes of dynamic yield a sense of vast, isolated space.

Echange, a terrifying and mysterious “concerto” for bass-clarinet and ensemble, is one of the darkest pieces in allmusic. The virtuoso solo part at times leans towards jazz, and the use of extended techniques make the bass-clarinetsound as you’ve never heard it before.

A unique work in Xenakis’ oeuvre, Xas (“sax” backwards) joins to growing repertoire for sax quartet. Though highlystructured, the work has a improvisatory feel which pays tribute to the sax’s prominent jazz heritage.

Okho, is a very rhythmic and appealing work for percussion trio playing djembes (a type of African conga drum withextreme bass resonance). Okho and Xas appear for the first time on an all-Xenakis CD.

Conductor Charles Zachary Bornstein is a Xenakis specialist who created the ST-X Ensemble to promote moreperformances of Xenakis’ music in the U.S.

Reviews

The critics had this to say about Volume 1 of Ensemble Works (Mode 53):

**** “…performed with total understanding and dramatic flair by this important new ensemble.”

–Art Lange, Tower Classical Pulse!

“…the level of performance and the importance of the pieces on this disc make it highly recommended. If you agree that Xenakis is one of the great creative forces of our time, then you’ll have to buy this disc.”

— Robert Carl, Fanfare

“Bornstein’s ST-X Ensemble pinned back my ears.”

— Mike Silverton, Fanfare

“…viscerally compelling as ever in these acute performances by the ST-X Ensemble under Charles Zachary Bornstein”

— P.D., The Sunday Times (London)

Iannis Xenakis

Ensemble Music 1

ST-X Ensemble / Charles Bornstein

Mode 53

Iannis Xenakis

Ensemble Music 2

ST-X Ensemble / Charles Bornstein

Mode 56

The model Xenakis utilised for the piece was that of light refracted through water, with the piano representing water and the brass portraying near blinding light, but this is no picture postcard representation. Splashy piano writing trickles everywhere with the power of 1000 simultaneous waterfalls. Underneath, muted brass enter imperceptibly until their reflection becomes a resonant reality; tidal waves of brass later overwhelm the piano as the two battle for supremacy. Another significant masterpiece is the Hebrew based N’Shima (1975) for two voices and instruments. The microtonal vocal writing is kept determinedly untamed for the niceties of the trained voice, and the clustery brass and amplified cello accompaniment equals their raw expressivity.

Then – rare in Xenakis – a joke, as a naked tonal fanfare in the ensemble appears without reason. Plektó (1993) is oddball again, featuring the pianist ricocheting clusters against a web of counterpoint from flute, clarinet, violin and cello. Xenakis usually locks counterpoint into his familiar sound masses, but here lines jut out provocatively. A mediating percussion part glues the whole raggedy enterprise together.

— Philip Clark, The Wire, July, 2006

Iannis Xenakis

Ensemble Music 1 & 2

Mode 53, 56

He Composes Differently, Therefore He Exists

At a time when so many composers have given up on radical innovation, the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who turns 75 this year, has become a heatening figure. His music, as represented in new recordings, is hardly less uncompromising than it was in the 1950’s, though it is certainly richer and more adept, probably because his successes while retaining an extraordinary imperviousness to his mistakes.

In more than four decades of working with orchestras he has developed a keen imagination for sound, generated by new playing techniques or, more usually these days, by assembling chords that works as single colors. But harmony and voice-leading still mean very little to him, insistent pulsation and scatter shots remain his most characteristic kinds of rhythm, and his musical forms are chains of events: chains sustained by the excitement of each moment and the timing of each jump.

The expressive result is aggressive, or not so much aggressive as defiant. Mr. Xenakis’s music is not trying to hurt but rather to protect itself: to stake out its territory and fence off any possibility that it might beheard in traditional ways. Only by being emphatically different, according to Mr. Xenakis, can his music answer the call he makes on it, which is to demonstrate that he exists.

“Composition, action are nothing but a struggle for existence,” he tells Balint Andras Varga in Mr. Varga’s recently published “Conversations with Iannis Xenakis.” “If I imitate the past, I do nothing, and consequently I am not. I am sure that I exist only if I do something different.”

By no means is this just some sort of exhibitionism. Exhibitionism need an audience; Mr. Xenakis, one senses from this book, is alone with himself, and his triumphs, in terms of public acclaim and colleagues’ imitation, are an embarrassment. For to achieve complete victory in his “struggle for existence” he would have to create something so different that to anybody else it would be totally meaningless.

Even he has not gone that far, though he has regularly traveled a long way into the desert of incoherence, often by calculating his music so as to maximize disorder. This is the main thrust of his mathematical techniques: his spinning numbers, like John Cage’s coin tossings, insure that notes are chosen and ordered by blind chance, or according to processes of change that have little to do with conventional musical perception.

What meaning remains will usually be crude, and it is striking that in his conversations with Mr. Varga, Mr. Xenakis so often equates beauty with savagery: in his fascination with weapons and armor, for instance, with the sea or with the bulls of the Camargue. In his music virtually the whole elaborate machinery of Western composition is set aside, and we are left with a brute vocabulary of other modernists – Stravinsky, Varèse, Harrison Birtwistle – avoidance of the immediate past leads to imagined contact with the archaic.

In the conversation book Mr. Xenakis recalls how, as a boy in Greece, he “went to the museum and tried to imagine how the statues would move if they suddenly came to life.”

“With what gestures?” he wondered. “How would they speak? What would the music of their language be like?” These are the questions his compositions have been answering.

Their answers, being removed from ordinary ways of doing things musically, requires particular efforts of virtuosity and imagination from performers if the music’s strength – its intense particularity – is not to seem mere incapacity. Happily there are musicians up to this challenge, and none more so than Charles Zachary Bornstein and his ST-X Ensemble, who gave us “Kraanerg” at Cooper Union in Greenwich Village in the fall and have now released two selections of smaller pieces on Mode CD’s. Each includes a 60’s classic – “Eonta” for piano and brass in one case, “Akrata” for symphonic winds in the other – along with more recent works.

Both recording convince by their own conviction; all the performances are hot. But the disc including “Eonta” (Mode 53) is a clear frontrunner.

It offeres the stark, urgent ritual “N’shima,” for two amplifies “peasant voices” with trombones, horns and cello; the percussion solo “Rebounds,” brilliantly played by Robert McEwan, and the best of all, “Akanthos,” a 10-minute drama of sibylline utterance in a context of clouds, braying and scrubbings of sound, all contrived, astonishingly, by an ensemble close to that of Ravel’s supersophisticated Mallarmé settings. The soprano Susan May is superb in producing the imprecations, formalized laughter, stunning octave leaps and final scanning of the horizon before wild yelps.

The other record (Mode 56), though, has the immense and strange attractions of “Échange,” a concerto for bass clarinet and ensemble, whose behemothian sounds glisten with harmonics.

It is remarkable how, in discussing some of these and other violently poetic works with Mr. Varga, Mr. Xenakis is unwilling to describe them as anything more than interesting sequences of interesting sounds. If the music is to assert his existence, perhaps it can do so only by being itself, and not by being about its composer, who must stand aside and let it happen.

“Eonta,” he recalls, came into his mind while he was at Tanglewood in Lenox, Mass., sitting in a boat with a pretty young woman. “We were surrounded by a forest, and I stroked the water with my hand,” he says. In the eventual eruptive work, though, listeners are left, as Mr. Bornstein’s note puts is, with “radiated light and cascading water”: a bucolic interlude has become fierce physics.

— Paul Griffiths, The New York Times, Sunday, January 26, 1997