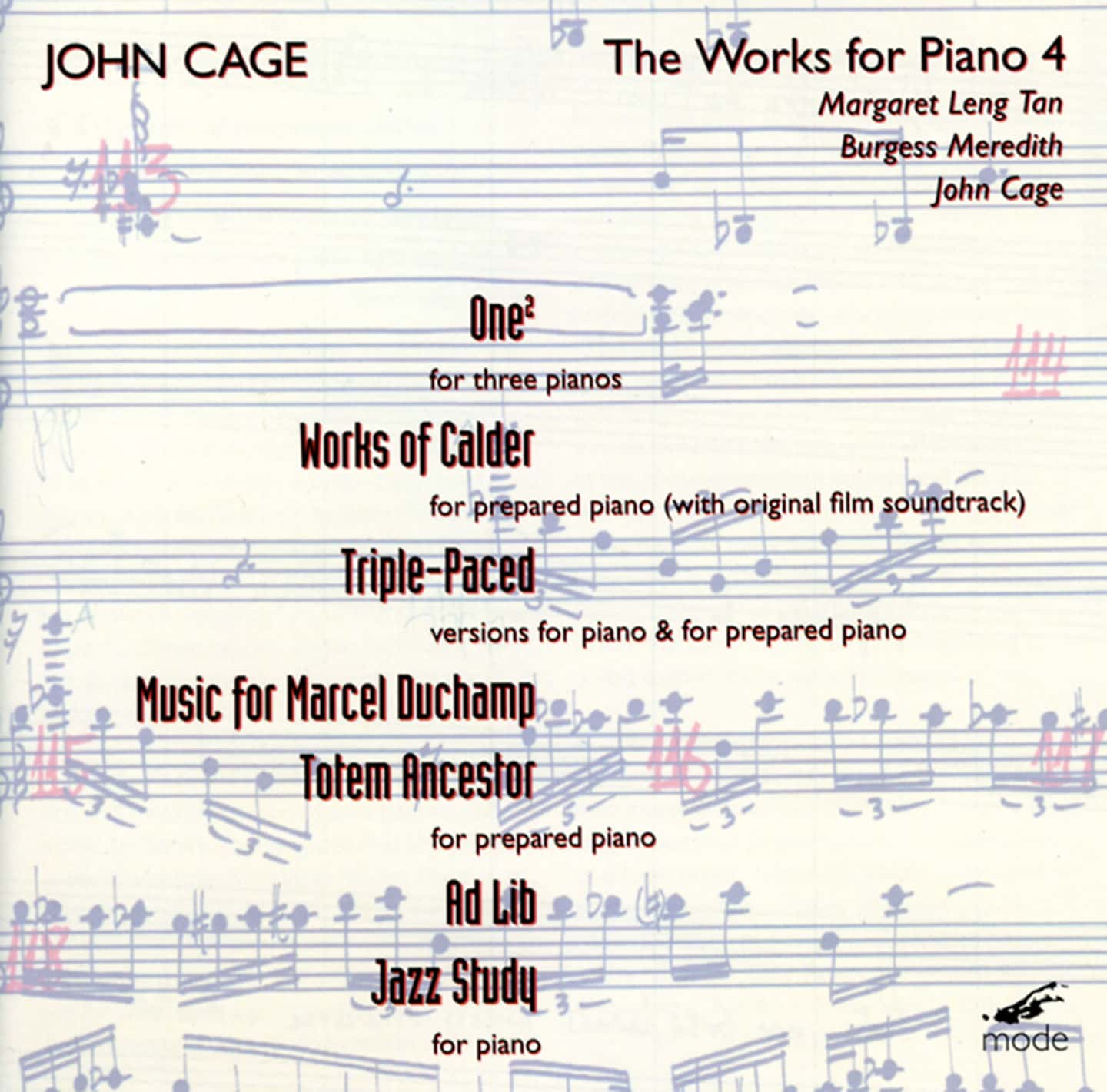

Cage Edition 25–The Piano Works 4

Margaret Leng Tan, pianos

John Cage, percussion & tape collage

Burgess Meredith, narrator

1-3. Triple-Paced (1943) (1:07, 1:01, 0:45)

first version, piano

4. Triple-Paced (1944) (2:04)

second version, prepared piano

5. Totem Ancestor (1942) (1:55)

prepared piano

6. Ad Lib (1943) (3:14)

piano

7. Jazz Study (1942) (3:03)

piano

8. Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947) (5:45)

prepared piano

Works of Calder (1949-50) prepared piano

9. I. Prepared Piano (5:05)

10. II. Film soundtrack with narration* (3:09)

11. III. Film soundtrack with percussion* (2:19)

12. IV. Prepared Piano (10:37)

* with Burgess Meredith, narrator, and John Cage,

percussion & tape collage

First recording

13. One2 (1989) (18:51)

for 1-4 pianos, 1 performer

Version for 3 pianos

Written for Ms. Tan

Until recently at C.F. Peters, Cage’s publisher in New York, there was a box of works which Cage had held off publishing or had simply forgotten about. Among them were the dance pieces, Triple-Paced and Ad Lib, Jazz Study, and the film score Works of Calder – all composed between 1942 and 1950. At Peters’ request, Margaret Leng Tan was enlisted to edit these works as part of a new volume of Cage’s piano pieces; they have been recorded here in conjunction with that publication.

Of great interest among these is Cage’s score for the film Works of Calder. Actor Burgess Meredith produced and narrated this documentary by Swiss filmmaker Herbert Matter on the artist Alexander Calder. Cage’s fluid prepared piano score is a major discovery, requiring an extensive preparation comparable in complexity to that of the Sonatas and Interludes. Composed in three-parts, Works of Calder‘s two outer movements are newly recorded by Ms. Tan. The middle section is taken directly from the original soundtrack as Cage composed and performed it – a percussion interlude enhanced by discreet electronic effects; and is presented here in its entirety.

Cage wrote One2 for Ms. Tan, who worked directly with him on the conception of the piece. It is to be performed by one player on one to four pianos; three are used here. The damper pedals of all the pianos are wedged so that the strings vibrate freely throughout the piece. The pianos become, in effect, sound sculptures where sustained resonances coalesce and gradually disappear. The result is an extraordinary sonic landscape, and a unique work in Cage’s oeuvre.

Reviews

John Cage

The Works for Piano 4

Mode 106

Margaret Leng Tan is widely regarded as the foremost living exponent of Cage’s piano music, and it doesn’t take much listening to see why. Art tells, whatever the repertoire. This is a musician from whom many of the world’s big league pianists could learn a lot. Her finger-sensitivity is perhaps unique in its fantastic breadth, subtlety and control. Her rhythm is phenomenally acute, and her mastery of tone colour is matched by her imagination in using it. But the most striking aspect of her Cage recital on Mode [MODE 106] is its expressiveness, its emotional immediacy.

— Alexander Letvin, PIANO magazine, The Pianist’s Record Shelf,

July/August 2004

John Cage

The Works for Piano 4

Margaret Leng Tan, piano

Mode 106

This piano CD offers delights that are more bite-sized. Many of these works come from the 1940s, shortly after Cage began experiments with “preparing” a piano by inserting various objects among and between the strings, but before he began serious examinations of indeterminacy in music. Totem Ancestor (1942), for example, is a tiny but perfect portrait-of-the-piano-as-a-young-gamelan, and Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947) rises in simple, ineffable spirals like the smoke from a hash pipe. Other works such as Ad Lib (1943) and Jazz Study (1942) are far less characteristic of Cage. They’re not particularly finished pieces, but they do sound intriguingly like Balinese jazz . . . should such a thing exist!

Works of Calder is a curiosity. In 1949, Cage began scoring a film documentary on the mobiles of sculptor Alexander Calder. The film’s text was by John Latouche, and the narrator was Burgess Meredith. Cage wrote two chunks of music for a heavily prepared piano, and Tan presents these two sections here. There’s also a track devoted to Meredith’s narration (what a fine voice he had!) and another to percussion music Cage improvised and assembled for another portion of the documentary.

In contrast, One2 was written in 1989, just three years before the composer’s death. (The title simply indicates that this was Cage’s second “number piece” for one performer.) The number pieces are highly indeterminate. For example, Cage specifies that one to four pianos are to be used; Tan uses three, arranged in a kind of circle with their lids open and sustaining pedals engaged to maximize their ability to “talk” to each other. There aren’t a lot of notes in One2, but there is a lot of music, and many decisions for the performer to make about when, where, and how long, concerning the musical instructions that Cage left behind. Tan’s long experience with Cage makes her the ideal performer for music such as this. At 18:51, One2 is a long meditation, and an unusual complement to what has preceded it on this CD.

Tan’s playing is full of devotion and understanding, and Mode treats it – and Cage’s music – with similar devotion.

— Raymond Tuttle, Classical Net, October 2002

John Cage

Works for Piano Vol. 4

Margaret Leng Tan

Mode 106 (58″)

AT FIRST HAND

Interpretation

Sound

Margaret Leng Tan belongs to that small number of musicians whose familiarity with the Cageanaesthetic universe was acquired through close personal collaboration with the composer. Forthis as well as for other reasons, she is considered among the best interpreters of his pianomusic.

In this Volume 25 of the Mode Collected Works of Cage, one’s attention is drawn to the smallestsound detail of this deeply probing, extraordinarily compelling and fantasy-filled recordingwhich also offers several posthumous rarities. For example, the surprising jazz-inspired Ad Lib(1943) and Jazz Study (1942), but above all the first recording of Works of Calder (1949-1950), the score to the documentary film of the same title by Herbert Matter. Besides thegently percussive sounds of the prepared piano accompanying Alexander Calder’s kineticsculptures and mobiles, the recording contains not only the original narration but also thetape of Cage himself playing the percussion interlude.

In context of the extra-musical works of the 40’s inspired by film and Cunningham’s dance, theascetic One2 (1989) is initially surprising. This late “number piece”, however, fits seamlesslyinto the programming concept: the performer-dedicated work for one to four pianos foregoesCage’s customary use of organized time brackets in favor of pronounced improvisatoryperformance elements and draws on all imaginable sound possibilities including those fromwithin the piano. Margaret Leng Tan explores the resources of three pianos whose wedged damperpedals make possible multi-layered resonances and overtones, weaving the dispersed individualsounds from the three self-contained scores into a sound odyssey of poetic magic andexpressivity.

— Dirk Wieschollek, Fono Forum, January 2003

(translated from the original German review below)

Aus erster Hand

Margaret Leng Tan gehört zu den wenigen Musikern, die Cages Ideenwelt noch in enger personlicher Zusammenarbeit kenned gelernt haben und zählt (nicht nur deshalb) zu den besten Interpreten seiner Klaviermusik. Das hört man bis in die kleinste Klang-Faser dieser tiefschürfenden, ungemein fesselnden und phantasievollen Aufnahmen, die im Rahmen der 25. Folge der Gesamteinspielung bei Mode auch einige Raritäten aus dem Nachlass zu bieten haben. Zum beispiel die überraschend Jazz-in-sprierten “Ad Lib” (1943)und “Jazz Study” (1943), vor allem aber die Ersteinspielung von “Works of Calder” (1949-50), einer Filmmusik zum gleichnamigen Dokumentarfil von Herbert Matter, die neben den zart-perkussiven Klängen des Prepared Piano, die Alexander Calders kinetische Skulpturen und Mobiles begleiten, nicht nur den originalen Erzähltext beinhaltet, sondern auch das Tape von Cages selbst eingespieltem Schlagzeun-Interludium.

Im Zusammenhang der außermusikalisch inspirierten Musiken aus den 1940er Jahren für Film und Cunningham-Tanz überrascht zunächst das asketische “one2” (1989). Doch fügt sich dieses spate “number piece” nahtlos ins Programmkonzept ein: Das der Interpretin zugeeignete Stück für ein bis vier Klaviere verzichtet zugunsten ausgeprägt improvisatorischer Performance-Elemnte auf die übliche “Zeitklammern” -Organisation und nutzt alle erdenklichen Klangmöglichkeiten auch im Innern des Klavieres. Margaret Leng tan erkundet drei Painos, deren verkeilte Dämpferpedale vielschichtige Resonanzen und Obertone ermöglichen und verbinder die verstreuten Einzelklänge der drei eigenständigen Partituren zu einer Klangreise von magischer Poesie und Expressivität.

Interpretation

Klang

— Dirk Wieschollek, Fono Forum, January 2003

John Cage

Works for Piano Vol. 4

Mode 106

Stretch Your Ears

A number of the compositions on The Works for Piano 4 by John Cage, performed by Margaret Leng Tan (Mode, distributed by Harmonia Mundi), were presumed to be lost until their discovery in an old box at the offices of Cage’s publishers in 1993. It was quite a find, as the sheaf of papers – works that the composer, who died in 1992, had either refrained from publishing or simply forgotten about – included some of his most tantalizing early scores, written in the 1940s for dance collaborations with the choreographer Merce Cunningham. Throughout the excellent recording, one hears intriguing evidence of Cage’s formative works with different variations of the “prepared piano” and experiments with percussion, jazz syncopation, Indian time-cycles and various Oriental and even Native American motifs.

The album begins with the terrifically energetic and uplifting “Triple-Paced“, created for the first collaborative recital of solo dances and music by Cunningham and Cage in New York in 1944. There are two versions of the piece, each singular enough to count as a separate composition. The first, divided into three brief mini-movements with a combined time of three minutes, is described by Leng Tan as “a conventional keyboard piece laced with glissandos played on the keys and on the strings”; in the second, written for prepared piano, cloth placed between the strings to dampen them produces a familiar Cagean gamelan-percussion effect.Succeeding pieces are even more revelatory. “Totem Ancestor“, written for the same Cunningham performance, uses what Leng Tan calls “a simple bolt and weather stripping preparation of 11 notes” to create a proto-minimalist series of Oriental-sounding percussive patterns, while “Ad Lib” and “Jazz Study” – dance pieces from 1943 and 1942 respectively – reveal Cage’s rather eccentric take on jazz. Elements of blues, boogie woogie, ragtime and what sounds like a paraphrasing of Ellington and Tizol’s “Caravan” jostle for precedence.

Music written for two films, “Music for Marcel Duchamp” (1947, the Cage-scored segment from Dreams That Money Can Buy), and “Works of Calder” (1949-50, this recording including the original narration by Burgess Meredith and percussion interlude by Cage himself), completes the album, together with the 18-minute 1989 composition, “One“, for written especially for Margaret Lent Tan, and performed on three pianos simultaneously.

— Phil Johnson, The Independent, January 2003

John Cage

Piano Pieces 4

Margaret Leng Tan

Mode 106

“Margaret Leng Tan, a remarkable pianist…just released a CD with little-known early Cage works of startlingly beauty and jazziness…”

— Mark Swed, The Economist, Aug 31-Sept 6, 2002

John Cage

Piano Pieces 4

Margaret Leng Tan, Burgess Meredith, John Cage

Mode 106

C.F. Peters found a box containing works composed by John Cage between 1942 and 1950 which either he had postponed publishing or had forgotten about altogether. This CD contains collaborations with Cunningham, Calder and Duchamp along with One2 composed in 1989. This great collection of works is brilliantly interpreted and flawless, capturing Cage’s childlike innocence along with the wisdom of a Zen master.

— Deborah Thurlow, New Music Connoisseur Cd Overviews

John Cage

Piano Pieces 4

Margaret Leng Tan, Burgess Meredith, John Cage

Mode 106 (59 minutes)

Once you’ve seen Margaret Leng Tan perform, you never forget her. There’s a theatrical air to her work and a demonstrative athleticism that’s absent from many other 20th Century piano specialists. Tan, a champion of John Cage’s piano music, made a fabulous recording of his early Four Walls for New Albion. From the time of her first Cage performances she continued to work closely with the composer, who wrote a new piece, One2, with her special gifts in mind. This release offers the premiere recording of that piece as well as a number of earlier compositions, all about to be published by CF Peters: Triple-Paced (1944), Totem Ancestor (1942), Ad Lib (1942), Jazz Study (1942), Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947), and Works of Calder (1949-50). Cage’s jazz-inspired works (the Study, obviously, and Ad Lib) make an odd impression: should they be played exactly like jazz, or as a kind of straight, classical filtering of jazz (like Milhaud’s Creation du Monde)? Tan takes the latter approach and the pieces take on a quaint, light-hearted tinge, like listening to American English spoken by a non-native. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but one day I hope a pianist thoroughly versed in jazz takes a look at these pieces.

I like Tan better in Totem and the Duchamp music. In the former, she batters the piano vigorously, and it sounds so exciting I almost feel as if the music is jumping out of the speakers at me. In the Duchamp work (a cue composed for the Duchamp sequence in the film Dreams That Money Can Buy) she impresses with her grasp of the mysterious sounds that populate Cage’s prepared piano music.

Her performance of the Calder piece (again, cues for a film) is even more extraordinary. Cage wrote this music at exactly the time he was making his transition to chance and indeterminacy, and she projects to perfection the musical stillness characterizing this shift. (As a bonus, Mode includes from the soundtrack the original remaining cues, performed by Cage, with Burgess Meredith’s narration.)

In One2, the pianist moves around the stage to different pianos, all with their damper pedals engaged so that the sound continuously reverberates. In the liner notes, Tan comments that Cage thought of the pianos in this work as “independent and interpenetrating entities” and that she “was merely the bell-ringer who went about sounding the bells while letting them speak for themselves”. The music does indeed seem tailor-made for her with its dramatic tremolos, and her performance shows the assertive spirit so typical of her style. Mode’s sonics are superb.

— Rob Haskins, American Record Guide, Sept/Oct 2002

John Cage

Roaratorio

An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake. Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake. Laughtears (Conversation on Roaratorio).

John Cage, voice; Various Irish musicians; etc.

Mode 28/29 [DDD] (2 discs: 76:25, 74:32)

John Cage

The Works for Piano 4

Triple-Paced (two versions). Totem Ancestor. Ad Lib. Jazz Study. Music for Marcel Duchamp. Works of Calder. One2

Margaret Leng Tan, pianos; John Cage, percussion and tape collage; Burgess Meredith, narrator.

Mode 106 [DDD] (58:55)

New York City-based Mode pushes forward with its John Cage collection, reissuing a new and improved Volume 6 (Roaratorio, etc.), and also Volume 25 (“The Works for Piano 4”), which is completely new, and which even includes a first recording: Works of Calder.

Many readers find James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake unapproachable. John Cage’s Roaratorio might be the best way of approaching this novel, as it condenses Joyce’s 600-some pages, through a process that is both cerebral and naïve, into an hour of spoken text that is remarkably faithful to the spirit of Joyce’s original. Furthermore, Cage’s melodious recitation – a poor description of the speaking, singing, and everything in between that Cage brings to his text – is complemented by a dense array of sounds associated with Joyce’s text. One can’t take it all in, but Joyce himself said that he didn’t intend Finnegans Wake to be understood, at least not in the conventional sense.

In short, Cage has constructed a long series of mesostics based on Joyce’s text, and on James Joyce’s name itself. (A mesostic is like an acrostic, but the letters that form the “hidden” message – here, the writer’s name – are in the middle of the words, not at the start of them.) For example, to create the “J” in “James,” Cage went through the novel until he came to the first word that had the letter “J” in it, which was “nathandJoe.” Then he continued until he came to the next word that had an “A” in it, which was “A,” and so on. (I’m simplifying, but you get the idea.) Cage created “JAMES JOYCE” mesostics for the entire novel in this manner. Next, for the “music,” Cage kept track of sounds mentioned in Finnegans Wake, and of places mentioned too. Cage obtained tape recordings of the sounds, and also of sounds obtained from the different places. These sounds were mixed into Cage’s recitation – not at random, but at locations where the text mentioned these sounds and places, whether those portions of the text actually remained in Cage’s mesostics or not. The result is truly a “circus” in that there is more than one center, one “ring” where the listener can fix his or her attention. Joyce’s statement “here comes everyone” comes figuratively true in Cage’s Roaratorio, a celebration of Finnegans Wake that is as daring and innovative as Finnegans Wake itself.

If this is too much to unravel, Mode’s two CD-set includes Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake, which is the Roaratorio text minus the Irish music and 62-track tape. There’s also Laughtears, which is a 30-minute conversation between Cage and Klaus Schöning of West German Radio, who collaborated with Cage in the production of Roaratorio.

This was a fairly early Mode release, and it now has been reissued with improved 24-bit digital remastering. An 80-page booklet of articles and a 44-page booklet of Cage’s text – cross-referenced to Finnegans Wake, so the curious can follow Cage’s process – make this release even more necessary for the Cage enthusiast. Anyone who simply likes the sound of the English language (and beyond!) should enjoy this too. And as I said, if you’re looking for a portal into Joyce’s odd world, this could be what you’re looking for.

The piano CD offers delights that are more bite-sized. Many of these works come from the 1940s, shortly after Cage began experiments with “preparing” a piano by inserting various objects among and between the strings, but before he began serious examinations of indeterminacy in music. Totem Ancestor (1942), for example, is a tiny but perfect portrait-of-the-piano-as-a-young-gamelan, and Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947) rises in simple, ineffable spirals like the smoke from a hash pipe. Other works such as Ad Lib (1943) and Jazz Study (1942) are far less characteristic of Cage. They’re not particularly finished pieces, but they do sound intriguingly like Balinese jazz . . . should such a thing exist!

Works of Calder is a curiosity. In 1949, Cage began scoring a film documentary on the mobiles of sculptor Alexander Calder. The film’s text was by John Latouche, and the narrator was Burgess Meredith. Cage wrote two chunks of music for a heavily prepared piano, and Tan presents these two sections here. There’s also a track devoted to Meredith’s narration (what a fine voice he had!) and another to percussion music Cage improvised and assembled for another portion of the documentary.

In contrast, One2 was written in 1989, just three years before the composer’s death. (The title simply indicates that this was Cage’s second “number piece” for one performer.) The number pieces are highly indeterminate. For example, Cage specifies that one to four pianos are to be used; Tan uses three, arranged in a kind of circle with their lids open and sustaining pedals engaged to maximize their ability to “talk” to each other. There aren’t a lot of notes in One2, but there is a lot of music, and many decisions for the performer to make about when, where, and how long, concerning the musical instructions that Cage left behind. Tan’s long experience with Cage makes her the ideal performer for music such as this. At 18:51, One2 is a long meditation, and an unusual complement to what has preceded it on this CD.

Tan’s playing is full of devotion and understanding, and Mode treats it – and Cage’s music – with similar devotion.

— Raymond Tuttle, Classical Net, www.classical.net, October 2002