Complete String Quartets

1. Gran Torso (1972) 21:38

2. Reigen seliger Geister (1989) 26:28

Composer supervised recording

3. Grido (2000-01) 25:24

For the JACK Quartet

“With a little help from my friends”

Once they called me their “father.” But when with them I feel fifty years younger, and they are my admired brothers. Each work – not only mine – when performed by the JACK, be it Beethoven or Feldman, becomes an incredible adventure of perception, a festival of intensity, touching our emotions and touching our intellect, making us remember that as human creatures we are full of possibilities and able to open our horizons infinitely. They are pure artists in that their humanity and virtuosity are one and the same: maybe they don’t know or aren’t aware of it, but that’s what they do: create happiness in the deepest sense.

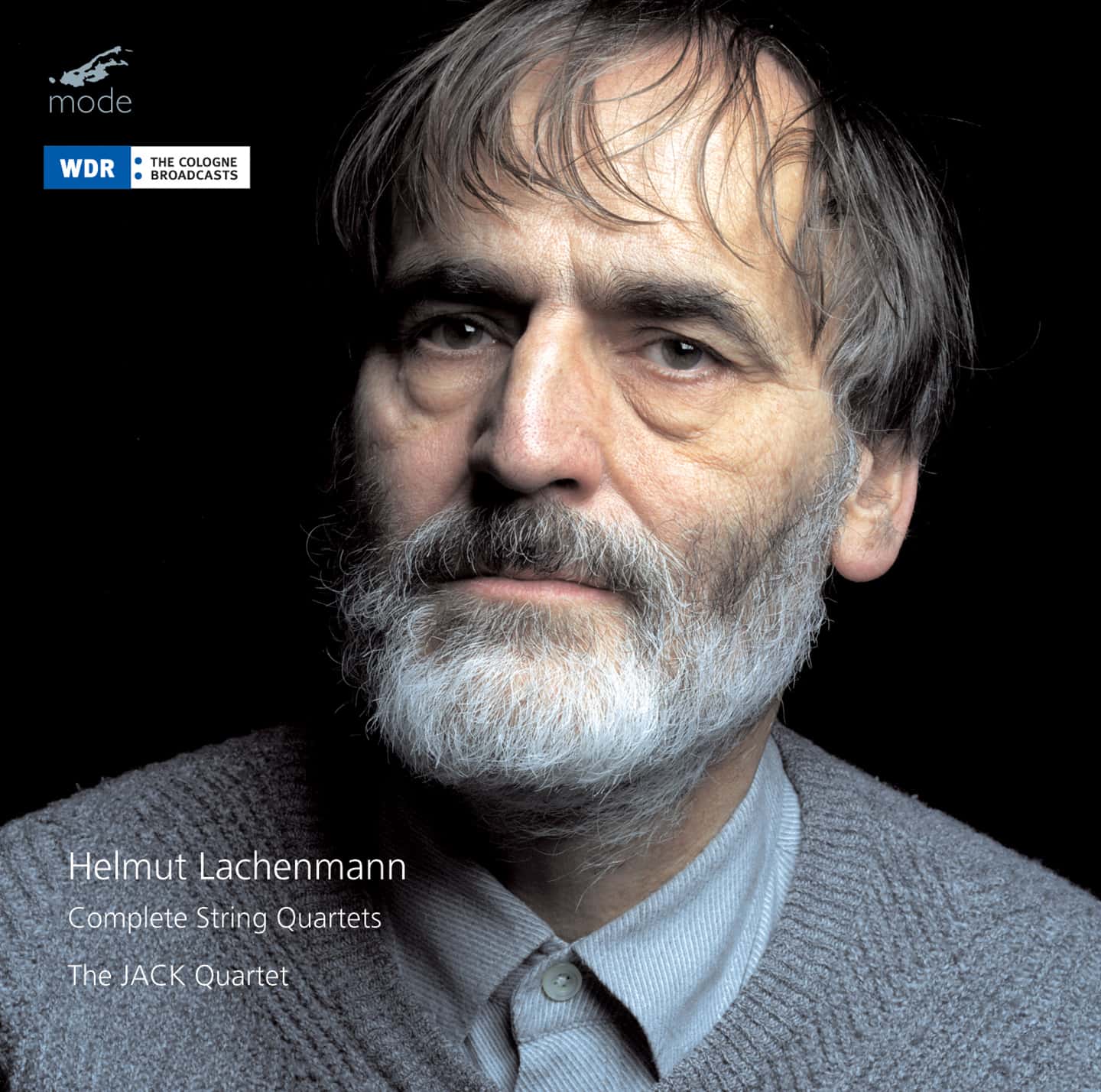

— Helmut Lachenmann

Leonberg, February 14, 2014

The JACK Quartet follow up their acclaimed, best selling release of Iannis Xenakis’ complete string quartets (mode 209) with a disc devoted to another iconoclastic European composer, Helmut Lachenmann.

Lachenmann has created a unique sound world which he refers to as “instrumental musique concrete.” It is a world where the musical atom is not the note but the sound, which may be drawn from the instrument in all kinds of unusual ways.

Strange as the soundscape may be, Lachenmann believes that the fundamental principles of music is about finding shape and continuity, about revealing the unexpected and touching the familiar, and that the string quartet, in particular, is about conversation.

Even through all the use of extended techniques, this is still a music of gestures, phrases, even melodies.

The JACK Quartet, specialists in new music, are the perfect performers for such repertoire. This recording is endorsed by the composer.

Liner notes by Paul Griffiths.

Reviews

String quartets by Helmut Lachenmann that will challenge and fascinate in equal measure on a new release from Mode Records, in extremely accomplished performances by the JACK Quartet

The German composer Helmut Lachenmann (b.1935) www.schott-music.com/shop/persons/az/helmut-lachenmann was born in Stuttgart and studied with Johann Nepomuk David (1895-1977) at the Stuttgart Musikhochschule and, later, with Luigi Nono (1924-1990) in Venice before working, briefly, at the electronic music studio at the University of Ghent.

He has lectured at Darmstadt and taught composition at the Musikhochschule Hannover. Lachenmann’s musical language embraces an entire sound-world made accessible through unconventional playing techniques though, in his later works, he has simplified his forms. Lachenmann has received many distinguished awards and, in 2008, was appointed Fromm Visiting Professor at the Music department at Harvard University.

His compositions include choral and vocal works, orchestral works, concerted works, chamber works and instrumental works as well as pieces for for one and two pianos.

Of his chamber works, the three String Quartets provide an excellent insight into Lachenmann’s sound world, ranging, as they do, from 1972 to 2000/01. Mode Records have just released a new recording of these quartets from the JACK Quartet www.jackquartet.com . Comprising violinists Christopher Otto and Ari Streisfeld, violist John Pickford Richards, and cellist Kevin McFarland, the JACK Quartet is focused on the commissioning and performance of new works and has worked closely with many contemporary composers including Helmut Lachenmann.

Gran Torso (1972) (String Quartet No.1) opens with rasps and strange harmonics with lightly played, bouncing bows. There are shrieks and outbursts before a short silent passage. When the silence ends, louder scrapings and percussive sounds can be heard, offset with little pizzicato notes. Slowly there are occasional longer bowed phrases to offset the sharper sounds. Little rising, sliding motifs also offset the sharper sounds, sounds that are like no other string sounds one has heard. A hushed section follows that soon grows into a fierce group of sounds, with sawing, shunting, rushing effects. This leads to another hushed, gently swirling section from which little motifs arise, all constructed with much sensitivity and care.

It is quite amazing how these players achieve such a sustained hush. Another pause precedes more hushed whispers from which new sounds arise, often percussive, sometimes like course breathing. The music continues in this vein for some time, with just the occasional outburst of sound until, eventually, the sounds become more dynamic with percussive sounds, the squeaks and rasps of the opening, pizzicato notes and short sharp sounds. Eventually a hovering background is heard from which the preceding sounds re-appear, even more dramatically, with growls and rasps from the players strings. Again a longer bowed phrase is heard but it is the strange sounds that take us soaring until we are grounded again by short, sharp little noises that grow ever quieter. There are sudden strikes on the strings, punctuated by pauses in the coda.

This is music that requires intense concentration. It is a difficult but very fascinating work, that requires the listener to cast aside accepted ideas, particularly on string playing technique.

A short phrase opens Reigen seliger Geister (Dance of the Blessed Spirits) (1989) (String Quartet No.2) before we are whisked around strange bowed string phrases reminiscent, at times, of Bartok’s night music. Lachenmann creates some incredibly strange sounds from his four string players, fleeting, shifting, quicksilver phrases that rush around, perhaps creating the image of the ‘Blessed Spirits’. Much of the music is hushed. A little way in, string sounds emerge from the hush in rushing, dynamic phrases, only to retreat into the quiet. Later long bowed phrases emerge at a variety of pitches around which quieter sounds are heard. Sharper, shrill high notes emerge. Eventually the whole quartet plays longer, louder phrases with dissonances as the music emerges more solidly than ever before. Short punctuated phrases appear shooting out, later dancing around, before becoming more agitated. Towards the end the music softens with little bow phrases and strange descending phrases, rasping in quality as the ‘Spirits’ seem to fade. There is a quiet shimmering background from out of which sounds emerge before silence pervades.

Grido (‘Cry’ or ‘shout’) (2000-01) (Third Quartet) brings rising and falling motifs that swirl around, developing in dissonance and dynamics. The music soon falls quieter but with little outbursts followed by even more hushed playing as curious phrases shoot out, each constantly changing. Soon there is a long held, unison, growling phrase that leads to a livelier, dynamic section, with each of the players providing a different motif. Passionate, anguished phrases appear, becoming increasingly frantic before becoming more quicksilver and fleeting. Later the intensity returns but eventually falls to a hush with just a background murmur and occasional sudden outbursts of a variety of sounds. The strings rise up and provide motifs high in the register before moving to a wider range of pitch, sounding off each other in an exciting section but, again, the music quietens before leading up to an insistent ‘drone’ from all players – almost like the drone of bagpipers, such is the harmony, which is always varying. Long held notes lead to a quieter section though with violent outbursts before the music falls to end on a single pizzicato note.

Of the three quartets on this disc this is the one that I would recommend starting with. The musical language, whilst still consistently Lachenmann’s, is easier to comprehend with more conventional use of instruments.

For many this is music that will strain the bounds of their understanding. Certainly this is very challenging music that requires the listener to cast aside accepted ideas.

The JACK Quartet provides extremely accomplished playing in this incredibly demanding music. The recordings, made between 2007 and 2011 at various venues are extremely good and there are interesting booklet notes by Paul Griffiths.

I must mention that the CD insert gives an incorrect timing for Gran Torso as 21’38 whereas it lasts 24’15.

— Bruce Reader, The Classical Reviewer, 4 July 2014

Lachenmann Complete String Quartets

Jack Quartet

MODE 267

“Lachenmann dares to propose that music might not be the whole story … the Jack Quartet feel their way expertly through this philosophically recalcitrant idea – the raw sounds behind the music can be revealed too.

— Philip Clark, Gramophone – July 2014

HELMUT LACHENMANN/JACK Quartet – Complete String Quartets

Helmut Lachenmann’s three string quartets, realized here in exemplary form by the JACK Quartet, are challenging investigations into the architecture of sound and sound production. In these three works, as in Lachenmann’s work generally, timbre is an independent musical value that interacts with or—more often—supplants pitch, harmony and rhythm as the central element of composition. As a result the focus of these quartets is on how sound is produced, modified and organized.

Listening to the string quartets is analogous to reading Finnegans Wake—both works are extremely dense in content and shades of meaning. In Lachenmann’s case the material is sound color in the various guises it can take as it is wrung from the conventional instrumentation of two violins, a viola and a cello. Although produced from standard orchestral instruments, individual sounds can be difficult to place. As with acousmatic music, their sources—meaning here the gestures used to produce them—can sometimes only be guessed at.

Gran Torso (1971), the first quartet, is the sound of acoustic instruments in extremis, its prominent clusters of pizzicato notes emerging creaks, rattles and the sounds of distressed wood, horsehair and strings. A long pause about ten minutes into the piece adds an element of structural enigma to match the sonic enigmas on either side of it. Reigen seliger Geister (1989) draws heavily on flautando playing and wind-like, pitchless sounds, as well as percussive and strumming gestures broken up by silences. Throughout the quartet tones are bowed in a way that reverses the usual attack-decay profile of the rapid or immediate attack and gradual decay, making for passages that sound as if they were run through a volume pedal. The final and most recent quartet, 2001’s Grido, embodies a brittle, often microtonally-flavored lyricism embedded in skittishly modernist phrasing.

In calling for unusual ways to produce sound from acoustic instruments, Lachenmann’s string quartets ultimately seem to be about the resistance of material to the energy applied to it. This resistance is implicit in all music—think of the tautness of the string pushing against the pressure of the bow as an ordinary tone is sounded—but Lachenmann takes this play of forces and pushes it to the point of crisis, amplifying it and thus bringing it to the center of the composition. Resistance reaches a crisis when instruments produce the kinds of sounds they weren’t designed or perfected to produce–one might say that the nature of the instrument itself resists the use to which it is being put. And it is from this that the drama of these quartets arises.

— Daniel Barbiero, Avant Music News, 19 May 2014