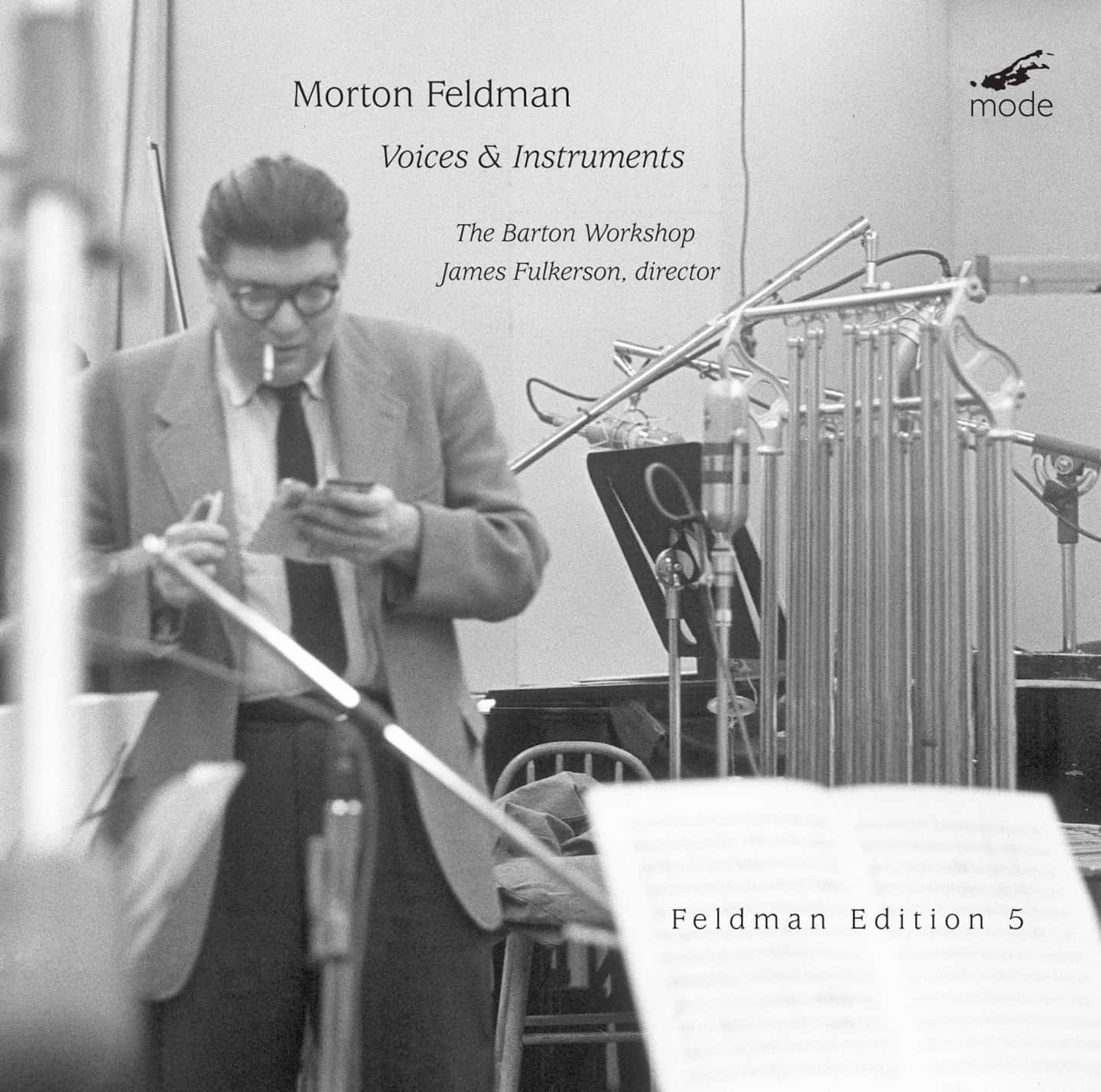

Feldman Edition 5–Voices & Instruments

Journey to the End of Night (1949) (2:11 – 1:12 – 1:00 – 2:37)

for Soprano, Flute, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet & Bassoon

*FIRST RECORDING

4 Songs to e.e.cummings (1951) (0:41 – 0:32 – 1:17 – 0:45)

for Soprano, Piano & Cello

Intervals (1961) (1:17 – 3:15 – l:58 – 2:39)

for Bass-Baritone, Trombone, Cello, Vibes & Percussion

*FIRST RECORDING

The O’Hara Songs (1962) (3:09 – 2:32 – 2:41)

Bass-Baritone, Chimes, Piano, Violin, Viola & Cello

Four Instruments (1965) (20:42)

for Chimes, Piano, Violin & Cello

Between Categories (1969) (12:29)

for 2 Chimes, 2 Pianos, 2 Violins & 2 Cellos

*FIRST RECORDING

Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano (1971) (9:32)

The Barton Workshop

James Fulkerson, trombone, conductor & director

with:

Claron McFadden, soprano

Charles van Tassel, bass-baritone

This CD is comprised of works from Feldman’s Early Period (late 40’s until the late 60’s) and Middle Period (late 60’s/ early 70’s until the early 80’s) of composing. In the beginning, like all young creative artists, Feldman was working through the influences he found alluring and the influence of his teachers, working for the moment that he would find his personal creative voice. With the previously recorded Only (on Etcetera, The Barton Workshop has now recorded all of the earliest works that Feldman chose to publish).

The first work on this CD, Journey to the End of Night (1949) shows unmistakable influences from his study with Stefan Wolpe yet it also shows a clear command of this musical language! It is a dramatically clear and forceful work. The text has been extracted, presumably by Feldman himself, from the long novel of the same title by Céline- the philosophy and critical stance of this text apparently struck a sympathetic chord with Feldman.

Although a student of Wolpe, Feldman was clearly heavily influenced by the work of Anton Webern. One hears the harmonic/melodic texture of Webern’s music not only in many of the notated works within the following 2 years of Feldman’s work – a period which includes the 4 Songs to e.e.cummings (1951), but to a large extent throughout Feldman’s entire oeuvre. This period of working through Webern was to prove seminal in Feldman’s artistic development, and the 4 Songs to e.e. cummings, with their extreme vocal demands, remind us firmly of Feldman’s fascination with the surface of Webern’s music.

In Intervals (1961), Feldman creates situations in which pitches or tonal colors will be picked up between the instruments-the texture could be described as a stasis or prolonged chord/color.

The O’Hara Songs (1962), notated in the same manner as Intervals, never uses all the instruments simultaneously with the singer. With regard to Frank O’Hara’s poem, Feldman uses it in its entirety, without any repetitions of words or phrases in the outer movements, while the inner movement uses only 5 repetitions a of single phrase of music/text: “Who’d have thought that snow falls”. It is a poem of striking tenderness, again revealing something almost contradictory about the often gruff, bear-like Feldman to us.

Four Instruments (1965), like The O’Hara Songs, is composed utilizing Feldman’s compositional/notational system wherein the players begin simultaneously but proceed at their own pace. In addition, Four Instruments and Between Categories, like the earlier Vertical Thoughts series, require the players to often listen carefully not only to the beginning and sustained parts of each note but also to play their next note just as another instrument is fading out. This is an extreme concentration upon the manner of beginning, sustaining and ending notes which no other composer has really explored. Such an extreme focus by each player must of course be matched with attentive listening by the audience.

Between Categories (1969) uses two identical ensembles separated in space. The ensembles, like most of his pieces from the 60’s, begin simultaneously, but in the case of ensemble 1, they begin with a silence! Through the use of two identical ensembles and shared materials (chords and arpeggiated material), Feldman underscores one’s sense of musical space.

In Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano (1971), Feldman was thinking of Cézanne, of painterly issues as they might apply to musical composition. The title is intentionally like the title of a still-life painting. This is considered a work in which he was returning to “flat textures”-he has set the melodic work of Clarinet 1 and the Cello off as foreground materials against the flat textures provided by the other instruments.

The superb performances come from The Barton Workshop, an Amsterdam based ensemble founded in 1989 by composer-trombonist James Fulkerson. The artistic philosophy of the ensemble is to perform the leading edge of contemporary music today. The Barton Workshop have a strong tradition of music by Wolff, Cage and Feldman. They have made many excellent recordings on the Etcetera label, this Feldman volume is their first of several to come dedicated to Feldman and Wolff.

Reviews

Morton Feldman

Voices and Instruments (Feldman Edition 5)

The Barton Workshop

James Fulkerson (dir.), Claron McFadden (sop.), Charles van Tassel (bass)

Mode 107

(70:40)

Judging by mails posted at the time, the fifth number of Mode’s otherwise excellent Feldman Edition was a somewhat controversial release for ‘Why Patterns?’ members. Grumbles centred on the CD’s production and its curiously dry tones, which raises some interesting questions about our expectations about how Feldman should sound. Certainly the uniqueness of the CD’s flattened sound is not in debate, nor is the fact that James Fulkerson has some justification for pursuing the singular nature of his vision. The levelling of instruments and the quest for non-hierarchical sound is a central characteristic of the Feldman oeuvre, but whether this should translate in practice as it does here is, I think, a matter of taste. My fear is that Fulkerson may have ‘levelled’ a little too much for most to happily follow and I personally find the sound a little uneasy and niggling at times: a distraction from the Barton Workshop’s performances.

That, however, is not to say that I do not value the experiment, or that I am closed to new approaches. There are two separate issues here that become folded when recorded music by Feldman is under scrutiny: one pertains to the democracy of the sound itself and the another to its high-fidelity reproduction. My assumption is that Fulkerson has attempted to push the first into the second in an effort to better present it to the listener in his/her living room, but the result is that levelling gives way to dryness. What is more worrying, however, is how this extends that perennial problem of how far the composer’s aesthetic should be openly submitted to in its interpretation and representation. By attempting to follow or mimic that aesthetic in terms of production, one furthers the democratic sound only by reinstating an aesthetic oligarchy with the ‘cult of the composer’ as its central component. The disc’s latest dated piece goes some way to indicating the possibility of the problems lying in wait here. In his liner notes for the fascinating ‘Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano’ (1971) Fulkerson writes:

The title is intentionally like the title of a still life painting. In general, this work is considered a work in which [Feldman] was returning to “flat textures” but I would venture that in the style of a still life – he has set the melodic work of Clarinet 1 and the Cello off as foreground materials against the flat textures provided by the other instruments.

The extension of the metaphor surely misplaces it. As he writes, Feldman may have been ‘thinking of Cézanne’ in the piece, but Fulkerson is still thinking in terms of Renaissance space. Without having Feldman here to supervisor or observe, one need readily admit that there is a very real danger in talking for him.

Even if the sound is not entirely to your liking, however, there is still much to recommend the disc by way of its content, not least the presence of three premier recordings: ‘Journey to the End of Night’ (1949), ‘Four Songs to e.e. cummings’ (1951) and ‘Between Categories’ (1969). Featuring the not inconsiderable talents of Claron McFadden, whose vocal performance in both pieces is particularly impressive, the first two of these works set words by Céline and Cummings respectively to the music of a young, Webern-influenced, Feldman. Both are curiosities that need to be heard by every Feldman fan and both differ enormously from the composer’s better known and even earlier setting of Rainer Maria Rilke in ‘Only’ (1946). Robust and muscular vocal workouts, they give us a chance to hear Feldman’s settings of two very different writers; the act rare in itself given that his later writing for voice is usually wordless. Likewise, the briefness of the Cummings songs and the difficult formal aspects of his poetry ensure that your attention will be captivated as the soprano (accompanied by piano and cello) summersaults through ‘air’, ‘(sitting in a tree-)’, ‘moan’ and the ever remarkable ‘!blac’.

To my mind, however, ‘Between Categories’ is the disc’s revelation and over the last couple of months it has rarely left my CD player. Scored for two small ensembles, each composed of chimes, piano, violin and cello, the twelve and a half minutes are sublime; Feldman extends the sort of patterning already found in the earlier ‘Four Pianos’ (1957) into a more complex spatial structure. Like the essay of the same name, this is an important transitional work for the composer and it seems remarkable that it has had to wait until now to receive its first recording. Recordings of ‘Intervals’ (1961), ‘Four Instruments’ (1965), and ‘The Frank O’Hara Songs’ (1962) complete the recital, which as a whole is provocatively programmed with the listener being catapulted back and forth through Feldman’s early and middle years. I find this time travel particularly thoughtful. A welcome change from chronological listings, it allows the listener to sense some of the more obtuse relations between Feldman’s pieces over the important period in question. Texts are included and the linear notes are extensive. Indeed, whatever one’s feelings about James Fulkerson’s production here, his take on Feldman is unique and he should be praised for that. His willingness to make an aesthetic stand in what are continually compromising times needs fair recognition. All things considered, it’s a disc worthy of your hearing.

— Alan Nicholson, Why Patterns? Website, 12 November, 2002

Morton Feldman

Feldman Edition, Volume 4 – ‘Indeterminate Music’

The Straits of Magellan. Two Pieces for Six Instruments. Projections. Durations.

The Turfan Ensemble / Arndt Heyer

(62 minutes: DDD)

Morton Feldman

Feldman Edition, Volume 5 – ‘Voices & Instruments’

Journey to the End of the Night. Intervals, Between Categories. Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano. Four Songs to e. e. cummings. Four Instruments. The O’Hara Songs.

Claron McFadden sop, Charles van Tassel bass-bar, The Barton Workshop, James Fulkerson tbn

(71 minutes: DDD)

Morton Feldman

Rothko Chapel. For Stefan Wolpe. Christian Wolff in Cambridge.

Kirsten Drope sop, Ulrike Becker contr, Barbara Maurer va, Meinhard Jenne perc, Markus Stange cels, Boris Muller, Martin Homann vibs

South West German Radio Vocal Ensemble, Stuttgart/ Rupert Huber Hänssler

Faszination MUSf 93 023 (61 minutes: DDD)

Projections, Durations-selected comparison: Barton Workshop, etc (ETCE) KTC 3003 Rothko Chapel-selected comparisons, Berkeley Univ Chbr Ch, Brett (10/92) (NALB) NA 039 CD Saarbrucken Radio Sym Ch and Orch, Furrer (3/01) (COL) WWE1CD 20506

Two varied Feldman banquets to tempt ‘gourmet’ and newcomer alike and one to kill the appetite altogether.

The Feldman feast continues, with two more volumes in the admirably planned Mode Series. The fourth is called “Indeterminate Music” and involves pieces such as the Projections series, where the score is laid out like a graph and the performers choose the specified number of pitches in high, middle or low registers. In the Durations pieces each player has a written part; they start together then proceed independently in what has been called racecourse design.

A good example of this is Durations 3 for violin, tuba and piano. Everything is soft: ‘dynamics are very low,’ Feldman says. The first three movements are slow, with only the higher notes of the tuba protruding like a distant fog-horn. Then the fast fourth movement is a surprise.

It’s extraordinary that both these techniques result in the unique Feldman sound and atmosphere but the players naturally bring a sense of the right style – Feldman once rebuked a student of mine for choosing a minor triad in the graph notation of Projection 2 when, as he put it, she had ‘all the sounds in the world to choose from’. It’s a good idea to have all the Projection and Durations pieces together, fastidiously played and recorded – plus the more lusciously scored Straits of Magellan and Two Pieces. However, there’s a three-CD set on Etcetera (listed above) which provides both of these plus the Vertical Thoughts series and much more.

‘Voices and Instruments’, the fifth volume in the Mode survey, is full of delights, including three first recordings. Now we can compare Feldman’s response to e. e. cummings with that of John Cage 13 years earlier. By 1951 Feldman is the more pointillistic, showing the influence of Webern but Claron McFadden is in complete command of the angularities of his extreme tessitura both here and in Journey to the End of the Night, which has a text from the novel by Louis-Ferdinand Celine. Charles van Tassel also feels exactly right in a more subdued role with The O’Hara Songs.

How rewarding to hear Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano (a British commission written for Alan Hacker) where every detail, including the plentiful silences, is precise – Feldman’s finesse requires that kind of dedication. Since so much of Feldman is soft and slow, the sole fortissimo in the work is a poised shock. Feldman enthusiasts will continue to buy the Mode series, which benefits from well-informed CD booklets with full texts, and it ought to make new converts.

(portion of the review covering the Hanssler release has been deleted here)

— Peter Dickenson, Gramophone, December 2002