Cage Edition 6-Roaratorio

1. Roaratorio: An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake (1976/79)

60:30. First CD recording

John Cage, voice

Joe Heaney, singer

Seamus Ennis, Uillean pipes

Paddy Glackin, fiddle

Matt Malloy, flute

Peadher Mercier, Mell Mercier, bodhran

with 62 track tape

2. Laughtears: Conversation on Roaratorio (1979)

30:55. First CD recording

John Cage and Klaus Schöning, speakers

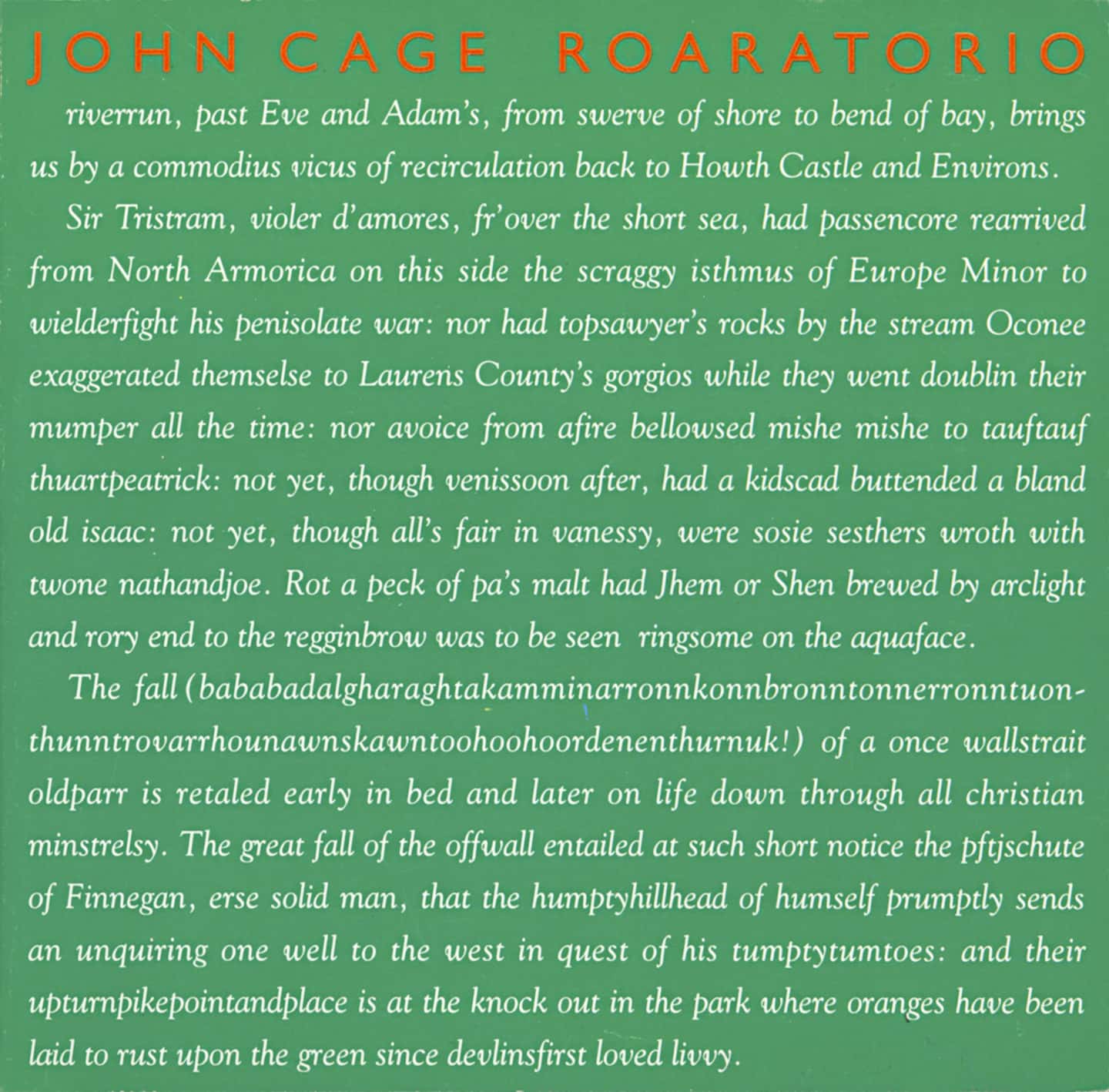

3. Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake (1976/79)

60:05 First CD recording

John Cage, speaker

NEWLY REISSUED IN JULY 2002, WITH THE FOLLOWING FEATURES:

- The return of ROARATORIO to the catalog, one of Mode Records’ biggest selling and most sought after releases, which has been out of stock for some time.

- New 24-bit remastering from the analog master tapes enhances the sound, revealing details as never before.

- Deluxe 2-CD set contains 2 books: an 80-page book of articles, photos and an interview with Cage as well as a 44-page book of the complete spoken text

- Winner of the prestigious French music press’ awards Diapason d’Or and Choc award from Le Monde de la Musique.

“Roaratorio is one of Cage’s most attractive larger assemblages…the piece is a landmark in the composer’s later output, and a credit to all involved in its elaborate realization.” – Peter Dickinson, Gramophone, 1994

Roaratorio was a commission from the West German Radio and IRCAM for Cage to realize a work based on his favorite book, Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. Cage began by making a text from the original (which became Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake, also issued here in its entirety), and cataloging the many sounds and locations mentioned in the book. A recording of each sound was made at the noted locations – virtually every sound/location was recorded. These were then laid out in the sequence in which they are mentioned in the Wake and mixed, along with Cage’s rendering of the text, into a massive collage of 62 tracks of tape lasting about an hour. Added to this is live accompaniment from leading Irish musicians on traditional instruments, performing traditional Irish music. The result is an enthralling stew of words, sound and music unlike anything you’ve encountered before.

Because Cage’s beautiful reading of the text often gets submerged in the density of Roaratorio, the unadorned recording of Writing for the Second Time… is also included. Special insight on the works can be had from Laughtears, with Cage interviewed by Klaus Schöning of the WDR regarding the project.

Language : English, Irish, French, German.

Reviews

John Cage

Roaratorio

Mode 28/29 (2CD)

“‘Finnegans Wake’ is one of the books which I’ve always loved and never read,” Cage announced amusingly at the Nova Convention in 1979, before patiently explaining how he constructed the mesostics on the name James Joyce which make up his “Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake”. When invited by Klaus Schöning to provide music to accompany his text, Cage reread Joyce’s book, painstakingly listing all the sounds mentioned in it, and defined a set of instructions based on chance operations for recording ambient sound in some of the 2462 places mentioned in the book as listed by Louis Mink in his “A Finnegans Wake Gazeteer”. From the outset, Cage imagined a “circus” featuring the Irish traditional music that underpins Joyce’s work, and travelled to Norwich to hear “the King of Irish singers” Joe Heaney perform in a local pub. Heaney agreed to participate and recommended Cage also use traditional Irish music for fiddle, flute, uillean pipes and bodhran drum. The resulting hörspiel “Roaratorio” represents not only the culmination of Cage’s concerns in the 1970s with text composition based on existing writings (notably Thoreau’s “Journal”), but its glorious 62-track tape montage of everything from Beethoven’s “Grosse Fuge” to police car sirens and bleating sheep also recalls the inspired mayhem of his “Variations III and IV” and even looks further back to his 1942 radio play with Kenneth Patchen, “The City Wears A Slouch Hat”.

With Mode’s typical concern for detail, the two accompanying booklets include Cage’s introduction to the work (a speech made at Donaueschingen in 1979), a somewhat edited (annoyingly so) 29-page transcription of “Laughtears” (a conversation with Klaus Schöning), and, in all its typographical glory, the complete 41-page text of “Writing..” itself. Each traditional Irish tune which appears is listed, as are the 1210 sounds of Cage’s “Listing”, ranging from farts to thunderclaps, and the instructions explaining how ambient sounds are to be “collected” at the places mentioned in the book. Cage’s score describes how to go about “translating a book into a performance without actors, both literary and musical or one or the other” – any book in fact, since the work’s correct title is “(title of composition), (article) (adjective) Circus On (title of book)” – in theory, listeners could have a go at producing their own “Roaratorio”, using Cage’s hour-long recording of “Writing”. One hesitates to use the word indispensable, but it’s surely justified for such a beautifully realised edition of a work featuring (arguably) the twentieth century’s most influential author and composer.

— Dan Warburton, The Wire

John Cage: Roaratorio; Laughtears; Writing for the Second Time through Finnegans Wake: Cage / Heaney / Ennis / Glackin / Malloy / Mercier / Mercier.

(Mode 2 CDs)

Though there has been a handful of live performances, John Cage’s Roaratorio, subtitled An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake, is essentially a work intended for radio, an hour-long horspiel, completed at IRCAM in Paris in 1979. James Joyce was a source of constant fascination for Cage, and Roaratorio is perhaps his most successful and most exuberant celebration of that. It is a taped collage built up from the composer’s readings of passages from Finnegans Wake, mingled with Irish folk music sung and played by Joe Heaney and his colleagues, and an array of “found” sounds from everyday life.

Typically the arrangement of the musical events was governed by the I Ching, but there is a special richness to this patchwork; of all Cage’s later works Roaratorio is perhaps the most approachable and the most immediately rewarding.

— Andrew Clements, The Guardian (London), Friday October 4, 2002

John Cage

Roaratorio

An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake. Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake. Laughtears (Conversation on Roaratorio).

John Cage, voice; Various Irish musicians; etc.

Mode 28/29 [DDD] (2 discs: 76:25, 74:32)

John Cage

The Works for Piano 4

Triple-Paced (two versions). Totem Ancestor. Ad Lib. Jazz Study. Music for Marcel Duchamp. Works of Calder. One²

Margaret Leng Tan, pianos; John Cage, percussion and tape collage; Burgess Meredith, narrator.

Mode 106 [DDD] (58:55)

New York City-based Mode pushes forward with its John Cage collection, reissuing a new and improved Volume 6 (Roaratorio, etc.), and also Volume 25 (“The Works for Piano 4”), which is completely new, and which even includes a first recording: Works of Calder.

Many readers find James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake unapproachable. John Cage’s Roaratorio might be the best way of approaching this novel, as it condenses Joyce’s 600-some pages, through a process that is both cerebral and naïve, into an hour of spoken text that is remarkably faithful to the spirit of Joyce’s original. Furthermore, Cage’s melodious recitation – a poor description of the speaking, singing, and everything in between that Cage brings to his text – is complemented by a dense array of sounds associated with Joyce’s text. One can’t take it all in, but Joyce himself said that he didn’t intend Finnegans Wake to be understood, at least not in the conventional sense.

In short, Cage has constructed a long series of mesostics based on Joyce’s text, and on James Joyce’s name itself. (A mesostic is like an acrostic, but the letters that form the “hidden” message – here, the writer’s name – are in the middle of the words, not at the start of them.) For example, to create the “J” in “James,” Cage went through the novel until he came to the first word that had the letter “J” in it, which was “nathandJoe.” Then he continued until he came to the next word that had an “A” in it, which was “A,” and so on. (I’m simplifying, but you get the idea.) Cage created “JAMES JOYCE” mesostics for the entire novel in this manner. Next, for the “music,” Cage kept track of sounds mentioned in Finnegans Wake, and of places mentioned too. Cage obtained tape recordings of the sounds, and also of sounds obtained from the different places. These sounds were mixed into Cage’s recitation – not at random, but at locations where the text mentioned these sounds and places, whether those portions of the text actually remained in Cage’s mesostics or not. The result is truly a “circus” in that there is more than one center, one “ring” where the listener can fix his or her attention. Joyce’s statement “here comes everyone” comes figuratively true in Cage’s Roaratorio, a celebration of Finnegans Wake that is as daring and innovative as Finnegans Wake itself.

If this is too much to unravel, Mode’s two CD-set includes Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake, which is the Roaratorio text minus the Irish music and 62-track tape. There’s also Laughtears, which is a 30-minute conversation between Cage and Klaus Schöning of West German Radio, who collaborated with Cage in the production of Roaratorio.

This was a fairly early Mode release, and it now has been reissued with improved 24-bit digital remastering. An 80-page booklet of articles and a 44-page booklet of Cage’s text – cross-referenced to Finnegans Wake, so the curious can follow Cage’s process – make this release even more necessary for the Cage enthusiast. Anyone who simply likes the sound of the English language (and beyond!) should enjoy this too. And as I said, if you’re looking for a portal into Joyce’s odd world, this could be what you’re looking for.

The piano CD offers delights that are more bite-sized. Many of these works come from the 1940s, shortly after Cage began experiments with “preparing” a piano by inserting various objects among and between the strings, but before he began serious examinations of indeterminacy in music. Totem Ancestor (1942), for example, is a tiny but perfect portrait-of-the-piano-as-a-young-gamelan, and Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947) rises in simple, ineffable spirals like the smoke from a hash pipe. Other works such as Ad Lib (1943) and Jazz Study (1942) are far less characteristic of Cage. They’re not particularly finished pieces, but they do sound intriguingly like Balinese jazz . . . should such a thing exist!

Works of Calder is a curiosity. In 1949, Cage began scoring a film documentary on the mobiles of sculptor Alexander Calder. The film’s text was by John Latouche, and the narrator was Burgess Meredith. Cage wrote two chunks of music for a heavily prepared piano, and Tan presents these two sections here. There’s also a track devoted to Meredith’s narration (what a fine voice he had!) and another to percussion music Cage improvised and assembled for another portion of the documentary.

In contrast, One² was written in 1989, just three years before the composer’s death. (The title simply indicates that this was Cage’s second “number piece” for one performer.) The number pieces are highly indeterminate. For example, Cage specifies that one to four pianos are to be used; Tan uses three, arranged in a kind of circle with their lids open and sustaining pedals engaged to maximize their ability to “talk” to each other. There aren’t a lot of notes in One², but there is a lot of music, and many decisions for the performer to make about when, where, and how long, concerning the musical instructions that Cage left behind. Tan’s long experience with Cage makes her the ideal performer for music such as this. At 18:51, One² is a long meditation, and an unusual complement to what has preceded it on this CD.

Tan’s playing is full of devotion and understanding, and Mode treats it – and Cage’s music – with similar devotion.

— Raymond Tuttle, Classical Net, www.classical.net, October 2002

John Cage: Roaratorio

mode 28/29

Elaborée à partir du célèbre Finnegans Wake de Joyce, l’oeuvre apparaît à la fois comme un homage, une derive et une amplification sonore du livre… Cage a établi un catalogue de sons enregistrés sur les lieux recensés dans l’oeuvre… Le travail des sons dans un esprit musical, à la manière du Horspiel (pièce radiophonique), soutient ou recouvre la voix douce et mélodieuse de Cage lecteur, et participe à la poésie mysérieuse de Joyce.

— Ecouter Voir, February 1992

John Cage: Roaratorio

mode 28/29

Cage’s Roaratorio was performed at the Proms for his seventy-fifth birthday in 1987. Those in the Royal Albert Hall were entranced by the multiplicity of acoustical activity on to which was superimposed the visual exhilaration of Merce Cunningham’s dance group. Some merely listening to the radio at home wrote to BBC to complain of a concert which sounded like crossed wavelengths with liberal helpings of static and feedback. But, like some of Cage’s other omnium gatherum pieces – Musicircus (1967) for superimposed concerts under one roof, or HPSCHD (1969) for masses of harpsichords playing Mozart (Elektra Nonesuch, 3/70-nla), or the variations pieces – Roaratorio is a rich assembly of involvements all stemming from James Joyce’s last so-called novel.

Cage started by making a text – a special kind of abridgement of the original – called Writing for the Second Time through Finnegans Wake. (This is published in its own right and is recorded here on its own by Cage, who also speaks it as the continuous element in Roaratorio.) Then Klause Schöning of West German Radio in Cologne asked him if he would like to put music to it to make a kind of radio play. So Cage decided to superimpose on to the text specially recorded sounds referred to in Finnegans Wake, as well as a live group of Irish folk musicians. These genuine folk artists were surprised to find that they were expected to perform, like Merce Cunningham’s dancers, regardless of whatever else happened to be going on at the time, but they soon got the hang of it and told me that it was the experience of a lifetime. The traditional pieces they played are listed in the magnificent CD booklet, which has full texts of Cage’s Joyce rewrite (still indestructibly Joycean) plus the text of the recorded interview between him and Schöning.

Roaratorio was a great success in Schöning’s radio series and won the Carl Sozuka Prize, with international broadcasts and performances to follow. All this took place in 1979 and what Mode have now released is the original production from West German Radio, which was supported by a variety of other organizations and required a large cast of technicians.

Roaratorio is one of Cage’s most attractive larger assemblages, completely logical if one approaches it, as he did, through the philosophy and sound-world of Joyce. Anyone interested in Joyce is bound to find it illuminating and, more than some of the smaller Cage works I have covered, the piece is a landmark in the composer’s later output, and a credit to all involved in its elaborate realization.

— Gramophone, October 1994

“Roaratorio is one of Cage’s most attractive larger assemblages, completely logical if one approaches it, as he did, through the philosophy and sound-world of Joyce. Anyone interested in Joyce is bound to find it illuminating and, more than some of the smaller Cage works I have covered, the piece is a landmark in the composer’s later output, and a credit to all involved in its elaborate realization.”

—PD, Gramophone