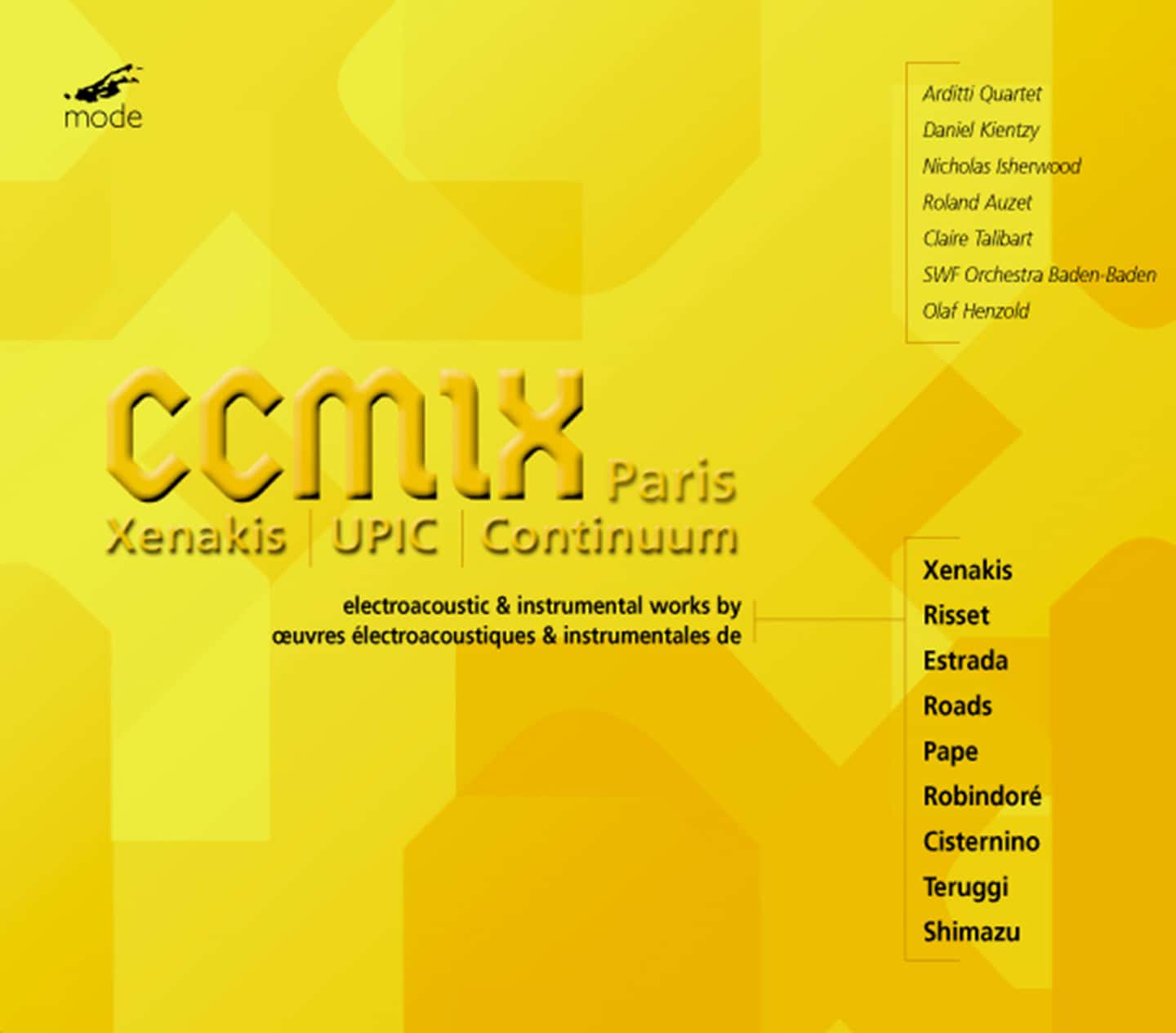

CCMIX Paris: New Electroacoustic Works

"Music computer-generated using the UPIC (Polyagogic Computer Instrument of CEMAMu), with additional acoustic accompaniment. Previously released as a compact disc. (viewed Feb. 7, 2013). Roland Auzet, Claire Talibart, percussion (3rd work) ; Daniel Kientzy, saxophone (4th work) ; Nicholas Isherwood, bass (5th work) ; SWF Orchestra of Baden-Baden ; Olaf Henzold, conductor (7th work) ; Kazuko Takada, san-gen, voice (10th work) ; Arditti Quartet (13th work). Recorded in 2009.

Iannis XENAKIS (1922-2001)

Mycenae Alpha (1978) for UPIC (10:00) *

Polytope de Cluny (1972) for 8-channel tape (24:45)

Brigitte ROBINDORÉ (b.1962)

L’Autel de la Perte et de la Transformation (1993)

for UPIC (8:33)

Comme Etrangers et Voyageurs sur la Terre (1994) (11:27)

for 2 percussionists & UPIC

Roland Auzet, Claire Talibart, percussion

Jean-Claude RISSET (b.1938)

Saxatile (1992) for soprano saxophone & UPIC (7:45)

Daniel Kientzy, saxophone

Nicola CISTERNINO (b.1957)

Xöömij (1997) for bass voice & UPIC (11:57)

Nicholas Isherwood, bass

Julio ESTRADA (b.1943)

eua-on (1980) for UPIC (7:44)

eua-on-ome (1995) for orchestra (10:42) *

SWF Orchestra of Baden-Baden, Olaf Henzold,

conductor

Daniel TERRUGI (b.1952)

Gestes de l’écrit (1994) for UPIC (11:00)

Takehito SHIMAZU (b.1949)

Illusions in Desolate Fields (1994) for voice, san-gen

& UPIC (13:27)

Kazuko Takada, san-gen & voice

Curtis ROADS (b.1951)

Purity (1994) for tape (7:13)

Sonal Atoms (1998) (3:41)

Gérard PAPE (b.1955)

Le Fleuve du Désir III (1994) for string quartet

& UPIC (12:41)

The Arditti Quartet

All FIRST RECORDINGS unless indicated by *

This 2-CD collection documents more than 20 years of works composed on the unique computer music system called “UPIC”, and the evolution of the computer music center founded specifically to promote it – Les Ateliers UPIC, now called CCMIX.

The UPIC system was conceived by Iannis Xenakis in the early 1950s; the first version of UPIC was built by Xenakis’ research center, the CEMAMu, in the late 1970s, and the system continues to be developed to this day. Instead of a keyboard to perform the music, the UPIC’s performance device is a mouse and/or a digital drawing board. These are used to trace the composer’s graphic score into the UPIC computer program, which the ninterprets the drawings as real time instructions for sound synthesis-the composition/performance of a graphic musical score and real-time sound synthesis are unified by the UPIC’s approach.

Xenakis’ Mycenae Alpha, the first work entirely realized on the UPIC, opens the set, which also includes the first issuance of his legendary Polytope de Cluny. In 1980, Julio Estrada composed his one and only UPIC work, eua’on, an experience that resulted in a veritable revolution in the composer’s approach. Also included is his large orchestral work eua’on’ome, an orchestral realization of the original UPIC score.In the 1990s, the UPIC system fascinated a whole new generation of composers including Brigitte Robindoré, Takehito Shimazu, Nicola Cisternino and Gerard Pape (CCMIX’s director). Jean-Claude Risset and Daniel Teruggi, coming, respectively, from the direct computer music synthesis, and the “acousmatic” approaches, also found ways to make the UPIC system their own in the 1990s.

Rounding out this collection are recent works by Curtis Roads and Xenakis’ classic tape composition Polytope de Cluny. These works have been included to demonstrate that Xenakis’ legacy-both in his own electroacoustic music as well as in his theoretical influence on other important electroacoustical composers, such as Roads-goes far beyond the UPIC system.

In 2000, Les Ateliers UPIC changed its name to CCMIX (Center for the Composition of Music Iannis Xenakis) in homage to this great creator.

Reviews

CCMIX: Electroacoustic Music from Paris

“One of the Best of 2001” – Dan Warburton

“Records of the Year” – The Wire

One of the Five Best of 2001 – The Wire

CCMIX: New Electroacoustic, Music from Paris

Mode 98/99 2xCD

UPIC is a computer system, devised by the late Iannis Xenakis and his researchers at the CEMAMu in the late 1970s, which allows the composer literally to draw the elements of the score using an electromagnetic pen. The first work composed for the new system was Xenakis’ “Mycenae Alpha”, which appropriately enough kicks off this two CD set of UPIC “greatest hits” (UPIC by the way has since changed its name to CCMIX: Centre for the Composition of Music Iannis Xenakis). This ten-minute piece, originally included in one of Xenakis’ mixed-media “polytopes” at the Acropolis in Mycenae is an nasty and uncompromising as you’d expect it to be; UPIC allowed Xenakis to generate his trademark glissandi with uncompromising precision, and he took full advantage of it.

The other pieces on offer are engaging but hardly as exciting: Brigitte Robindoré (born 1962) wrote “L’Autel de la Perte et de la Transformation” (“the Altar of Loss and Transformation”) in 1993, presumably under the influence of her teacher Julio Estrada’s Continuum Theory (of which more later) and “Comme Etrangers et Voyageurs sur la Terre”, translated curiously here as “As Strangers and Pilgrims on the Earth”, a year later. This latter calls for two percussionists who play along with UPIC (use it also made of modified gamelan samples). Both works are spacious and pretty, if somewhat soporific. Jean-Clause Risset’s “Saxatile” (1992) for soprano sax (Daniel Kientzy) and UPIC is also disarmingly attractive stuff, its chirping cheeky Varèse quotes (unintentional, probably) presumably designed to reassure the genteel, ageing New Music audience that they have nothing to fear. Argentinean Daniel Teruggi, these days head honcho at the GRM in Paris, turns in a solid but unsurprising eleven-minute piece, entitled, somewhat unimaginatively, “Gestes de l’écrit”. Takehito Shimazu’s “Illusions in Desolate Fields” provides some welcome breathing space, juxtaposing hi-tech UPIC sonic scribbles with delicate work from Kazuo Takada on voice and san-gen. Californian Curtis Roads contributes two brief but effective pieces, “Purity”, an austere seven-minute study in microtones, and “Sonal Atoms”, a three and a half minute crunchy hit single that deserves to be heard in its full spatial glory rather than on a humble stereo CD. Gérard Pape’s “Le Fleuve du Désir III” finds the Arditti Quartet drowning in the eponymous river while waves of digitized passion wash over them – it’s a sincere if slightly harrowing swim. The “sonic graffiti” of Italian Nicola Cisternino’s “Xöömij” for bas voice and UPIC was written in 1997, and its title (pronounce it at your peril) refers to a kind of oriental throat singing – the work is marked “homage to Bruce Chatwin”, whose musings on Aboriginal oral culture are liberally quoted. It’s a fascinatingly grizzly twelve minutes of threatening guttural growls, and I’d like to see how the native population of central Australia would react to Nicholas Isherwood’s performance. (I don’t think my downstairs neighbour appreciated it much, though that’s nothing new.) Julio Estrada’s “eua-on” (1980) is the Mexican-born composer’s only electronic composition, but a work of key importance in his output, in that its creation led directly to the notion of a “continuous macro-timbre, a free sum of the components of frequency, amplitude and harmonic content of rhythm (duration, attack and vibrato) and sound (pitch, intensity, colour) and physical space in two or three dimensions.” Digitising his own voice and working hands-on with the UPIC machine enabled Estrada to exorcise his own grief at the loss of his father, the resulting 7’44” proving to be one of the most powerful pieces of electronic music of recent time, and arguably the best thing to come out of UPIC. Estrada ultimately extended and “transcribed” the piece for orchestra, and “eua-on-ome” rounds off disc one in style.

It’s ironic, however, that the strongest work on offer here – and it’s well worth buying the album just for it – was created several years before UPIC saw the light of day, and uses good old eight-track tape and distinctly recognizable source sounds and minimal use of external electronic source sounds or system: Xenakis’ “Polytope de Cluny” (1972) is a MONSTER, twenty-five minutes of visionary sonic apocalypse, easily on a par with his legendary tape works such as “Bohor”, and proof (if any were needed) that great music originates in the mind of man and even the most sophisticated technological wizardry available might facilitate its realization but will ultimately only ever be a means to end – not an end in itself.

— Dan Warburton, Signal to Noise, Spring 2002

HOMMAGE À XENAKIS

LE MUR DU SON

CCMIX: New Electroacoustic Music from Paris

Mode 98/99

Les personnes intéressées à entendre davantage de musiques de Xenakis et à constater l’influence qu’il a exercée sur ses contemporains auraient avantage à se procurer le très beau compact double du Centre de création musicale Iannis Xenakis CCMIX: New Electroacoustic Music from Paris, paru chez Mode à la fin de l’année dernière (#98/99). On y trouve des pièces réalisées grâce au système UPIC (Unité Polyagogique Informatique du Centre d’Études de Mathématique et Automatique Musicale un stylo électromagnétique relié à un ordinateur convertissant le dessin de la partition en sons), inventé par Xenakis. La première réalisation de Xenakis avec ce système, Mycenae Alpha (1979), est ici reproduite, de même que son Polytope de Cluny (1972), pour bande. Des oeuvres de Brigitte Robindoré, Jean-Claude Risset, Nicolas Cisternino, Julio Estrada, Daniel Terrugi, Takehito Shimazu et Gérard Pape, toutes réalisées sur UPIC, côtoient celles de Xenakis. Livret en français et en anglais.

— Réjean Beaucage, Voir, n° Volume: 16 Number: 11, 21 mars 2002

CCMIX: New Electroacoustic Music from Paris

Mode 98/99

UPIC is a computer system, devised by the late Iannis Xenakis and his researchers at the CEMAMu in the late 1970s, which allows the composer literally to draw the elements of the score using an electromagnetic pen. The first work composed for the new system was Xenakis’ “Mycenae Alpha”, which appropriately enough kicks off this two CD set of UPIC “greatest hits” (UPIC by the way has since changed its name to CCMIX: Centre for the Composition of Music Iannis Xenakis). This ten-minute piece, originally included in one of Xenakis’ mixed-media “polytopes” at the Acropolis in Mycenae is as nasty and uncompromising as you’d expect it to be; UPIC allowed Xenakis to generate his trademark glissandi with uncompromising precision, and he took full advantage of it.

The other pieces on offer are engaging but hardly as exciting: Brigitte Robindoré (born 1962) wrote “L’Autel de la Perte et de la Transformation” (“the Altar of Loss and of Transformation”) in 1993, presumably under the influence of her teacher Julio Estrada’s Continuum Theory (of which more later) and “Comme Etrangers et Voyageurs sur la Terre”, translated curiously here as “As Strangers and Pilgrims on the Earth”, a year later. This latter calls for two percussionists who play along with UPIC (use is also made of modified gamelan samples). Both works are spacious and pretty, if somewhat soporific. Jean-Clause Risset’s “Saxatile” (1992) for soprano sax (Daniel Kientzy) and UPIC is also disarmingly attractive stuff, its chirping cheeky Varèse quotes (unintentional, probably) presumably designed to reassure the genteel, ageing New Music audience that they have nothing to fear. Argentinian Daniel Teruggi, these days head honcho at the GRM in Paris, turns in a solid but unsurprising eleven-minute piece, entitled, somewhat unimaginatively, “Gestes de l’écrit”. Takehito Shimazu’s “Illusions in Desolate Fields” provides some welcome breathing space, juxtaposing hi-tech UPIC sonic scribbles with delicate work from Kazuko Takada on voice and san-gen. Californian Curtis Roads contributes two brief but effective pieces, “Purity”, an austere seven-minute study in microtones, and “Sonal Atoms”, a three and a half minute crunchy hit single that deserves to be heard in its full spatial glory rather than on a humble stereo CD. Gérard Pape’s “Le Fleuve du Désir III” finds the Arditti Quartet drowning in the eponymous river while waves of digitised passion wash over them – it’s a sincere if slightly harrowing swim. The “sonic graffiti “of Italian Nicola Cisternino’s “Xöömij” for bass voice and UPIC was written in 1997, and its title (pronounce it at your peril) refers to a kind of oriental throat singing – the work is marked “homage to Bruce Chatwin”, whose musings on Aboriginal oral culture are liberally quoted. It’s a fascinatingly grizzly twelve minutes of threatening guttural growls, and I’d like to see how the native population of central Australia would react to Nicholas Isherwood’s performance. (I don’t think my downstairs neighbour appreciated it much, though that’s nothing new.) Julio Estrada’s “eua-on” (1980) is the Mexican-born composer’s only electronic composition, but a work of key importance in his output, in that its creation led directly to the notion of a “continuous macro-timbre, a free sum of the components of frequency, amplitude and harmonic content of rhythm (duration, attack and vibrato) and sound (pitch, intensity, colour) and physical space in two or three dimensions.” Digitising his own voice and working hands-on with the UPIC machine enabled Estrada to exorcise his own personal grief at the loss of his father, the resulting 7’44” proving to be one of the most powerful pieces of electronic music of recent times, and arguably the best thing to come out of UPIC. Estrada ultimately extended and “transcribed” the piece for orchestra, and “eua-on-ome” rounds off disc one in style.

It’s ironic, however, that the strongest work on offer here – and it’s well worth buying the album just for it – was created several years before UPIC saw the light of day, and uses good old eight-track tape and distinctly recognisable source sounds and minimal use of external electronic source sounds or systems: Xenakis’ “Polytope de Cluny” (1972) is a MONSTER, twenty-five minutes of visionary sonic apocalypse, easily on a par with his legendary tape works such as “Bohor”, and proof (if any were needed) that great music originates in the mind of man and even the most sophisticated technological wizardry available might facilitate its realisation but will ultimately only ever be a means to end – not an end in itself.

— Dan Warburton, The Wire, 2001

Links

Iannis Xenakis on Mode:

Iannis Xenakis Profile/Discography

Arditti Quartet on Mode:

John Cage: The Complete String Quartets Vol. 1 (mode 17)

The Complete String Quartets Vol. 2 (mode 27)

Vol. 19 – The Number Pieces 2 – Five3 for trombone &

string quartet (mode 75)

The Works for Violin 5 (mode 118)

The Works for Violin 6, The String Quartets 4

(mode 144/145)

Elliott Carter – Quintets and Voices (mode 128)

Chaya Czernowin: Afatsim: Chamber Music (mode 77)

Peter Maxwell Davies: Le Jongleur de Notre Dame (mode 59)

Alvin Lucier: Navigations for Strings; Small Waves (mode 124)

Gerard Pape (mode 26)

Bernadette Speach: Reflections (mode 105)

Xenakis, UPIC, Continuum: Electroacoustic &

Instrumental works from CCMIX Paris (mode 98/99)

Nicholas Isherwood on Mode:

“In the Sky I am Walking”: works of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pascal

Dusapin and songs of the Native Americans. (mode 68)

Alain Bancquart: Le Livre du Labyrinthe (mode 120/121, 2-CDs)

Mauricio Kagel: Phonophonie for bass voice & tapes. (mode 127)

Luigi Nono: A floresta é jovem e cheja de vida (mode 87)

Gerard Pape on Mode:

Gerard Pape: (mode 26)

Electroacoustic Chamber Works (mode 67)

Alain Bancquart: Le Livre du Labyrinthe (mode 120/121, 2-CDs)

The Arditti Quartet Profile

Nicola Cisternino profile

Julio Estrada profile

Nicholas Isherwood profile

Gerard Pape profile

Jean-Claude Risset profile

Brigitte Robindoré profile

Curtis Roads profile

Takehito Shimazu profile

Daniel Teruggi profile

Nicholas Isherwood Online<