Reviews

Quintets and Voices

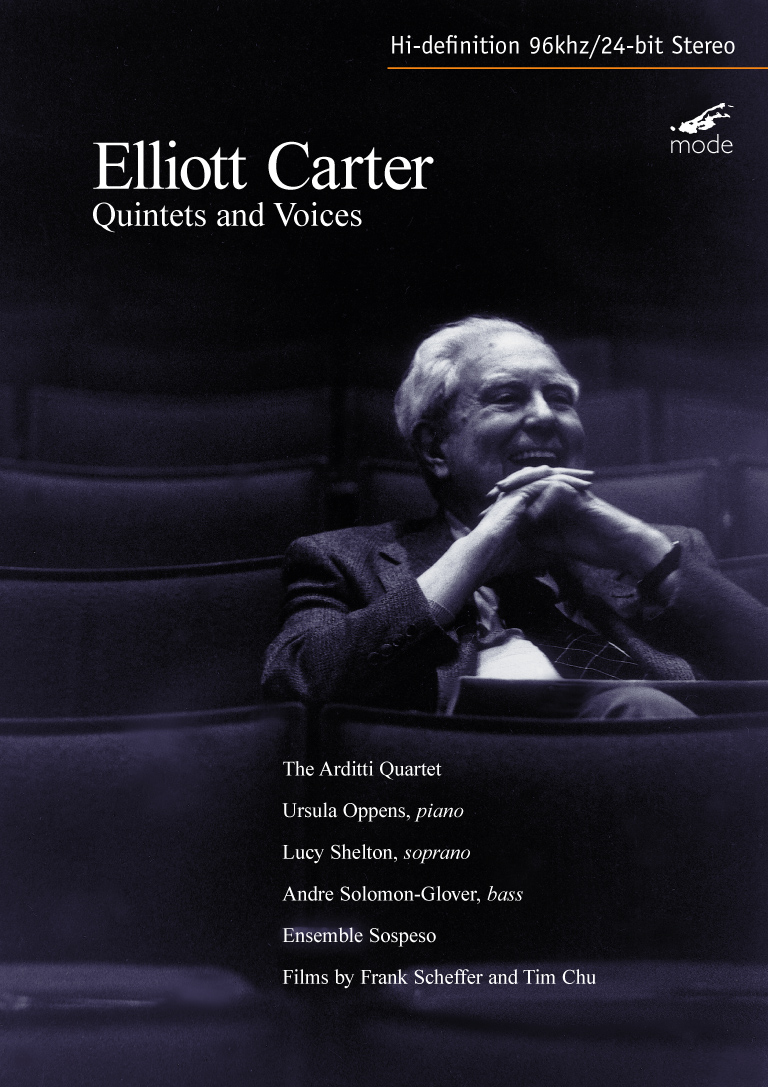

Would that there were more discs like this. It represents effectively a concentrated portrait in high definition sound and video (on the DVD) of recent works by Elliott Carter, who will be 103 in December. Bearing the title Quintets and Voices this excellent offering from new music specialists, Mode, contains half a dozen major works by Carter – all written in the 1990s with the exception of Syringa (1978). They are played superbly by their respective performers, several of whom also gave their premières. Mode’s Brian Brandt explains in the liner notes that the idea for the disc came from Irvine Arditti as a result of the reception accorded to Carter’s piano quintet. It’s a choice collection of the composer’s work. The quintet is unavailable elsewhere and both Syringa and the vocal works have only one or two other recordings. The DVD (with the extra material) is considered here. But there is also a CD-only version, also on MODE 128. Since the DVD can be found for only 50% more than the CD and contains material of such significance, it’s surely worth the extra.

Fragment II for string quartet dates from 1999 and was written for the Ardittis; it uses contrasts and a kind of dialog emphasizing the dualities, in fact, as much as the differences between song and sudden bursts of energy. It’s hard to imagine a more persuasive and suave performance than that given here by the Ardittis. Retrouvailles is for piano solo. It was written in 2000 for Boulez’s 75 birthday and contains a motto using letters from his name. It lasts less than two minutes and is expertly played by Oppens.

The Quintet for Piano and Strings was written in 1997 as one extended movement though with sections that divide the music in time; and interplay of dissimilar musical elements… especially between piano, and strings. As with so many of Carter’s other works, it’s against this strongly structured sense of sequence and development that harmonies operate. The performers, though, appreciate that Carter is in no way attempting to disorientate us or provoke shock by the mere presence of sound. Similarly, the Quintet for Piano and Winds of 1991 explores the drama of how instruments from the different families (piano, horn and reed) work with, within and against one another. It’s played out chiefly through again energetically expressed tempi and harmonics that support and illuminate such dramas. The performances are compelling, precise and full of import and weight.

The two vocal pieces are Syringa for soprano, bass and ensemble, which sets John Ashbery’s treatment of the Orpheus myth. Curiously, although the interview on the DVD throws doubt on the etymology of syringa, the piece is yet another treatment of the ground-breaking (literally: the flower is also known as saxifrage, which breaks through rocks) and the emergent power of sound. A living organism the result of shards. Tempo e Tempi for soprano, oboe, clarinet, violin and cello (1998) is almost as long, at over a quarter of an hour. It also is a form of quintet – for soprano, violin, cello, oboe and clarinet. The poet is Montale and the aura again one of flow; yet flow in opposition, almost, to tiny fragments of sound. Ensemble Sospeso performs with true and striking adroitness in each case.

There is a long (40 minute) filmed conversation on the DVD that makes as compelling watching as the musical performances make compelling listening. Dating from 2000, Carter, Irvine Arditti, Ursula Oppens with Joshua Cody explore the experience of listening to and performing new music: the excitement of hearing contemporary music for the first time; and growing with it especially when the composer is able to provide input, as Carter often does – and did in these cases; the relationship between what a living composer expects (and demands) and how multiple performers develop multiple interpretations; and how this feeds into what composers then produce. The three discuss how the String Quintet was conceived as an example of Carter’s compositional process: how fragments combine, the inspiration, the privilege of being a work’s first performer.

Film maker Tim Chu has captured splendidly the relaxed intimacy of Cater, Oppens and Arditti as they reminisce (though not self-indulgently: we’re genuinely interested in what they remember). And as they dissect the essence of Carter’s music… the relative roles of the instruments and instrumental combinations in particular. Particularly valuable are the insights that Oppens and Arditti offer into the multitude of ways in which Carter provides as many means for instrumental expression as he does – without relying unduly on Extended Techniques; indeed at one point Carter describes himself as a deconstructed classicist whose music should “flow like the air.” We hear the terms “float”, “flow” and other expressions of continuity often. That these are so aptly used to describe the essence of Carter’s music is a tonic. They also describe this conversation.

Carter’s charisma (not to mention his modesty) is always a compelling and engaging aspect of watching (and listening to) him talk not only about his music but about the cultural context (ofSyringa, for instance). The body language and pace of the conversation of Oppens and Arditti as they discuss the works on the disc are infectious. Pauses and smiles, questions, ribbing, allusions, gentle “throw-away” lines; and also intense, focused description. Above all, pointed exchanges always illuminating the music. The informality of this discussion should not disguise the value it has in expanding our understanding of this area of contemporary music in general, and Carter’s in particular. Almost worth the modest price of this DVD alone.

Dutch film maker, Frank Scheffer’s, film of the Arditti Quartet with Ursula Oppens playing Carter’s Quintet for Piano and Strings is beautiful. Apart from capturing an occasion (a performance in the 13 concert tour of the Arditti Quartet) it delves and probes the players’ work, their faces, gestures and almost physical interactions with the printed score as well as with one another. Lacking spectacular effects or superfluous filmic techniques, this short item on the DVD recreates a sense of presence at the performance highly appropriate for the small screen – though the quality would surely be good enough for the big one.

Mode’s usual high standard of production is well in evidence on this DVD. The sound quality is excellent and adds to our enjoyment and appreciation of Carter’s music for smaller forces. Intended to be played on “any DVD player”, the disc certainly worked on all those tried for this evaluation. The booklet (with notes by Paul Griffiths) provides useful background information and – together with the other inserts – confers just the right feeling of an integrated product, presenting for as wide an audience as possible the music of one of the world’s most accomplished and stimulating composers. Warmly recommended for anyone who loves Carter’s music and is interested in the conception and performance of modern music in general.

– Mark Sealey, classicalnet

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Mode 128 (CD/DVD)

La música de Carter se sostiene sobre una concepción muy particular de la escritura instrumental, que no es sino una suerte de dramaturgia que, fundada en una estratificación del tiempo en la que evolucionan las identidades musicales en continua progresión, debe tanto a la herencia de un Ives y a los renovadores del lenguaje americano (Cowell, Varèse) como a Debussy, Stravinsky o la los compositores contrapuntistas del Renacimiento. En su obra, los caracteres musicales ligados a las configuraciones melódicas, armónicas o rítmicas, así como a identidades instrumentales y a sus respectivas relaciones, juegan un papel esencial y tienen por misión sustituir la noción de una subjetividad de tipo romántico ni tampoco están sujetos a una estética de la imitación, sino que poseen un valor estructural por sí mismos.

Desde fìnales de los 50, la idea tradicional de tema desaparece, pues, en la música de Carter en beneficio de un nuevo tipo de identidad musical que todos los analistas coinciden ed señalar como “caráctermusical” y que abrirá, nuevas posibilidades de desarrollo al discurso sonoro. Desde el Cuarteto n° 1, los caracteres musicales sostendrán las relaciones jerárquicas en el seno de la música de Carter. En su etapa final, y con una edad muy avanzada, que no le impide una vitalidad creadora insultante, ya en plenos años 90, Elliott Carter concibe cuatro obras mayores: la ópera What’s next? (publicada recientemente en el sello ECM), el Cuarteto n° 5, grabado por el sello Montaigne, la Symphonia, editada en DG y el Quintet for piano and stings, escrito en 1997, dos años después del formidable último cuarteto, y que ahora aparece grabado en este sensacional disco del sello Mode, que contiene, además, otra página cuartetística del autor, el breve, lacónico, pero no menos intenso Fragment II, de 1999, las dos piezas para voz y conjunto Syringa, un clásico de su catálogo, de 1978 y la extraordinaria cantata en once secciones Tempo e Tempi. A todas estas obras, de una calidad excepcional, el disco aporta una página de cámara de 1991 de una menor complejidad de escritura, el Quintet for piano and winds y la brevísima pieza para piano solo Retrouvailles, la más moderna de todas, compuesta en pleno año 2000. Carter, que nació, hay que recordarlo, en 1908, parece acometer el hecho musical a sus más de 90 años como si partiera de cero. El suyo no es un compromiso con las nuevas técnicas instrumentales, sino con el mantenimiento del lenguaje desde su misma esencia. En carter, la Historia de la Música se conserva y, al mismo tiempo, se renueva sin que, aparentemente, ocurran grandes cataclismos.

Los sucesos y grandes dramas que Carter expone en su música están íntimamente ligados a la estructura de cada pieza, lo que pide un considerable esfuerzo en la escucha. Cada obra de las aquí grabadas (el Quintet for piano and strings, Tempo e Tempi) nace con unos principios y unos fundamentos que no se distinguen demasiado de los que sostienen la sonata clásica para, a lo largo del discurso, derivar hacia diseños totalmente personales. Tal vez el secreto de esta música esté, como señala Paul Griffiths al inicio de su comentario en el libreto que acompaña al registro, en el empleo del tiempo por parte de Carter. Griffiths repara en el milagro que supone este uso del tiempo, “tan elástico, tan multiforme”, pero su comentario tiende hacia lo poético. Se sabe que Carter elabora su música a partir del diseño de ámbitos temporales en los que la simultaneidad de los fenómenos sonoros es tan importante como la sucesión lineal. Quizás asî se pueda explicar el planteamiento de obras como el portentoso Quintet for piano and strings, en donde, por momentos, se asiste a vertiginosas secuencias en las que, mientras el piano dibuja un material propio, habría que decir tendente al virtuosismo, las cuerdas (espléndidamente servidas, como es norma, por el Cuarteto Arditti) sostienen el armazón con es todo un hallazgo, un paso adelante más en la asunción de Carter de unos tempi lentos (adagios, talvez) de desmedida belleza que ya habíamos saboreado en el Cuarteto 5° y en la Symphonia. La idea de tragedia preside en toda esta música. Carter plantea sus partituras como una suerte de diálogo, de discusión, normalmente exasperada, entre individuos que aquí toman el carácter de instrumentos de música, pero que, en realidad, pueden trasplantarse a los comportamientos humanos.

No todo el disco Mode es de un nivel de exigencia extremo. El Quintet for piano and winds es de una escritura más sencilla, por lo que resulta fácil, tras los fuertes contrastes instrumentales y los encadenamientos abruptos del material de partida, seguir la arquitectura de la pieza, amparada en amplios desarrollos. Aquí, el color armónico y la conducta de las líneas horizontales priman sobre el gesto y la virulencia de la acción dramática. Tento el diseño de producción como las tomas de sonido son ejemplares en esta grabación que, además cuenta, como ya quedró apuntado, con unos pertinentes análisis (después del texto inicial, escrito en un tono poético, poco convincente) a cargo de Paul Griffiths. Las interpretaciones, no ya sólo del Arditti y la pianista Ursula Oppens, sino del formidable Ensemble Sospeso en Syringa y en Tempo, son demostraciones palpables del alto nivel de exigencia con el que trabaja Mode.

La producción, en cambio, en el registro del sello Bridge, en el que es el volumen quinto de su integral Elliott Carter, no es tan brillante. Las interpretaciones son excelentes (Charles Rosen, nada menos, al piano en Two deiversions y la reciente y excelente Trouvailles), pero las tomas de sonido carecen de la claridad y el sentido de espacialidad que se perciben en Mode. El peso de la música baja también algún grado en este registro de Bridgr. Se trata sobre todo de piezas de corta duración, minuaturas degran fuerza expresiva, compuestas en los dos primeros años del siglo XXI para instrumentos solistas, un campo sonoro muy querido especialmente para el disfrute de los intrumentistas a quienes están dedicadas las piezas: Steep. Steps, para clarinete, Figment 1, para chelo o las que están a cargo de Charles Rosen. Sólo el Oboe quartet, escrito para el Speculum Musicæ, está elaborado para un conjunto de cámara más amplio y se distingue del resto de las piezas en ser la que acoge con más fidelidad el estilo de Carter. La aparente sencilles formal da como resultado, tras la disputa entre los distintos caracters representados por cada instrumento, otro discurso de alto voltaje, el que solamente puede concebir un autor para quien el lenguaje de la música ha supuesto un resto formidable obra tras obra durante más de seis decenios.

—Francisco Ramos

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Mode 128 (CD/DVD)

Carter’s piano quintet bustles with five discordant voices that crisscross like fidgety, mutually oblivious, determined travelers in a cramped waiting-room. The Ardittis and Oppens’ assertive playing foists an impenetrable sheen over the single movement which should surprise no Carter fan. There is something right about the music’s angularity which on repetition reveals ambiguous questions and ambivalent answers. Mode’s DVD release adds Frank Scheffer’s arty film of the piano quintet in performance (discussed here) and a disjointed interview with Carter, Irvine Arditti (who looks like he’d rather be playing than talking), Oppens and Joshua Cody.

Absent flute, the reedy quintet for piano and winds (oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon) is tougher to penetrate, perhaps because the burnished hues combine in unfamiliar ways. Carter doesn’t suppress his fondness for the oboe (this and other oboe-prominent works having been commissioned by Heinz Holliger), yet there’s some rather extraordinary horn and bassoon writing – and playing – here, too. Syringa, with simultaneous Classical Greek and English (John Ashbery) settings, receives a superb performance. Tempo e Tempi could be considered the release’s third quintet. Its resonating acoustic contrasts with the other, drier venues. Solo piano Retrouvailles and Fragment II for string quartet are typical Carter trifles, which means they’d be complex multi-layered epics for other composers. The brief quartet is elegantly characteristic: individual lines progressing at different rates that briefly intersect before scurrying away. The Ardittis seem to relish the assignment.

—Grant Chu Covell, La Folia online review, March 2005

Sunday Times’ (London) Records of the Year 2004:

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Mode 128

This superb disc includes the first recordings of Fragment II, for string quartet, and Quintet for Piano & Strings; and the first CD appearance of his classic Syringa, a setting of a John Ashbery poem and a cantata of rare force.

Sunday Times’ (London) Records of the Year 2004

Elliott Carter – Quintets and Voices

John Cage – From Zero

Mode 128 (DVD)

Mode 130 (DVD)

DVDs a la Mode

A classical music video is a predictable affair. One can expect to see wide shots of the performers, with the occasional cuts to the audience and the hall itself to establish the atmosphere. Someone in the control room shows off knowledge of the score as the camera zooms in on a player just about to begin a solo. This annoying practice virtually commands the viewer, “This is what you should be listening to now.”

A different and more rewarding model for how such videos might work is presented in two recent DVDs on Mode featuring films by the Dutch director Frank Scheffer. Focusing on the music of Elliott Carter and John Cage, Scheffer’s works suggest that such films might convey the compositional principles behind the musical works they document. Of course his composer subjects could not be more dissimilar in those principles, and a very different kind of film emerges for each.

The film Quintet for Piano and Strings appears on the DVD Elliott Carter: Quintets and Voices (Mode 128, 2003). It begins in near obscurity behind pianist Ursula Oppens, and the camera seems intent on revealing as little as possible about the identity of the performers. As the Quintet unfolds, the members of the Arditti Quartet gradually come into view, but rarely is more than one player at a time the focus of a shot. The players are attempting to work together, as furtive glances from one to another show, but the gulf between them is wide. A striking sequence early on confirms this. We see Irving Arditti, the first violinst, in a shot from behind cellist Rohan de Saram, looking up toward him with a serious expression. Immediately following we see de Saram from behind Arditti, and we feel almost as if they looked at each other from the opposite sides of a canyon. We also begin to get the sense that the piano is trying to insert itself into the gap, with Oppens visually in the center, striving to communicate with both sides – or perhaps as the driving force in the wedge between them.

Many of the shots that follow are closeups of the players, some decidedly uncomfortable. It is only within the last two minutes of the film that we begin to see something of the big picture, as the camera pans from one side of the quartet to the other. However, we never see all five players together, but an alternation between the viola and cello on one side, and the violins on the other. Grouped with the latter is the piano, which seems to succeed at last in fracturing the quartet. Here the camera feels most expressive, trying to bring the five performers together at the finale. But in a brilliant stroke Scheffer allows the camera to fail and a final unity is never achieved.

Readers who have spent time with Carter’s music will recognize several of its more prominent themes in the structure of the film. Perhaps most notable is how Scheffer captures the intensity of individuality that is at the heart of Carter’s approach to writing for instruments. The film explores the interaction of those individuals in a variety of ways, some more cooperative, some more antagonistic. In fact, while the main tension is between the piano and the string quartet, the latter is not simply singing with one voice, either in the music or in the film. Thus, in idiomatically cinematic ways, Scheffer has produced a visual analogue of Carter’s compositional practice.

This process is more overt in Scheffer and Andrew Culver’s collaboration titled From Zero: Four Films on John Cage (Mode 130, 2004). Of special interest here is a performance of Cage’s work, Fourteen, by the Ives Ensemble. Like all of Cage’s late number pieces, the instrumentalists are assigned parts which contain mostly single notes and chance-distributed time brackets indicating the period of time (as measured by a stopwatch) within which the notes are to be played. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Fourteen is the presence of a bowed piano which contributes sounds of extended duration. The piano, alone, plays continuously, as Cage indicates, “an unaccompanied solo…in an anarchic society of sounds.”

In order to film the work, Scheffer and Culver decided on some anarchic principles of their own, providing Cage-like scores for a team of “undirected camera performers,” for lighting, and eventually for editing. The result is a mesmerizing essay in Cagean “anarchic harmony” in multiple dimensions that enhance one another, facilitated by the shimmering sonorities of complex harmonics that the composer draws from the ensemble. In the film’s most arresting sequence a camera slowly pans across a trumpet and its player, mostly out of focus (characteristically, the trumpet is not being sounded at this point). The trumpet seems like three points of light, then several, and only gradually does the actual form emerge. Meanwhile a complex sound grows out of rich but uncertain harmonics that glisten much as the trumpet does as it moves into and out of focus. As for the solo piano, no one feature of the lighting or editing seems to correspond to it – until one remembers that the only constant through the film is the viewer, alone in an anarchic society of images.

The Carter and Cage DVDs contain additional materials of considerable interest. From Zero includes three other films by Scheffer and Culver, all of which incorporate chance operations to some extent. In 19 Questions, Cage speaks on randomly selected topics for periods of time also determined by chance. In Paying Attention, Culver and Scheffer work like Cage and Merce Cunningham, with Culver manipulating the audio portions of a Cage interview while Scheffer plays with the visual sequences, without either knowing what the other is doing. The last film, Overpopulation and Art, overlays the composition Ryoanji, interpreted both in sound and film, with Cage’s reading of a mesostic recorded in the last year of his life. The result is a moving memorial. Valuable interviews with Culver and Scheffer place the films in context.

The Carter DVD contains an interview with Arditti, Oppens, Joshua Cody and the composer. But the most valuable parts of the DVD are the performances in very radiant sound. The Quintet receives a second, tighter, reading, but there is also the more boisterous Quintet for Piano and Winds and the beautifully paced Syringa and Tempo e Tempi performed by the Ensemble Sospeso. Scheffer’s excellent new Carter documentary, A Labyrinth of Time, will be released soon by Mode. Recently premiered at the 2004 Tribeca Film Festival, it is not to be missed.

—Anton Vishio, Institute for Studies In American Music Newsletter

Volume XXXIII, No. 2, Spring 2004

Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of NY

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Mode 128 (CD/DVD)

Elliott Carter can be considered as one of the United States’ (and the world’s) major composers not only of the twentieth century, 92 years of which he has already lived through, but – as he shows no sign of letting up – of the beginning of the twenty-first. This magnificent celebration of Carter’s recent music (one hesitates to use the word “late” lest it be misinterpreted – remember JFK and Marilyn..) is therefore a major release. Carter is one of the last great masters – and here the word “last” is, sadly, maybe appropriate – of a school of composition that still believes that pitch and rhythm are of primary importance. Any Carter score from the 1950s onwards provides rich pickings for analysts well-versed in set theory looking for sophisticated applications of pitch class phenomena, but his investigations into rhythm at the micro and macro level are also hugely important, representing as they do an attempt to transpose structural procedures derived from pitch into the domain of tempo, an attempt as theoretically coherent (and arguably more musical) than Milton Babbitt’s time point system. Apart from its compositional craftsmanship, Carter’s music quite simply sounds great; die-hard modernists who believe that the time-honoured procedures of development towards and away from climax are old-hat should think again. The earliest composition here, “Syringa”, dates back to when Carter was a sprightly youngster at age 70; the remaining five offerings were written between 1991 and 2000. It’s available as a standard CD or a DVD, the video element of which consists of a beautifully realised if slightly arty film document of pianist Ursula Oppens performing the 1997 piano quintet with the Arditti Quartet, and a 40-minute interview with Oppens, Irvine Arditti and Carter himself conducted by the Sospeso Ensemble’s Joshua Cody (who, as readers of PT will know, was one of the founders of this organ, back in the days when it was published in print format as the Paris New Music Review).

“Syringa”, which sets fragments of Greek poetry (sung by a baritone) simultaneously with poetry by John Ashbery (sung by a mezzo-soprano), revisits the Orpheus myth. The spiky interjections of the accompanying eleven-piece ensemble, notably the acoustic guitar, fleetingly recall Boulez’s celebrated “Le Marteau sans Maître”, and Carter is, along with Boulez (and Nono), one of very few composers of his generation able to write highly complex lines for singers that are still eminently singable and comprehensible for the listener. “Tempo E Tempi”, dating from twenty years later, reveals the same mastery. Setting a cycle of Italian poetry, by Eugenio Montale, Salvatore Quasimodo and Giuseppe Ungaretti, the work is simultaneously a song cycle for soprano and ensemble (oboe, clarinet, violin and cello – members of the Ensemble Sospeso, making its impressive recording debut) but also a quintet – Carter’s ear for pitch and contour is as acute as ever, and despite the work’s macro-rhythmic complexity (reminding us that “tempo” translates as “time” and “tempo”), attentive listening reveals the myriad cross-connections and exchanges between the five participants.

Along with Josh Cody and PT Publisher Guy Livingston, I was fortunate enough to have attended the French premiere of the “Quintet for Piano & Strings”, and vividly remember us all leaving the Maison de la Radio in a state of euphoria, which I’m happy to report returns with each subsequent listening to this 1997 minor masterpiece (minor only in that it lasts just fifteen minutes – but what glorious minutes!). By now, the music press has practically exhausted the supply of superlatives to describe the playing of the Arditti Quartet and pianist Oppens, so I won’t bother to try to find more here. The “Quintet for Piano & Winds” dates from six years earlier, and continues Carter’s ongoing investigation into instruments as distinctive dramatis personae. The composer refers to an “interplay of commentary, answer, humorous denial, ironic, supportive or self-effacing”, but the work is far from a facile attempt to have musical instruments play out stock dramatic clichés. It’s a tough, abstract but supremely lyrical span of music, performed with exemplary attention to detail by Oppens and a wind quartet consisting of Steve Taylor, Charles Neidich, William Purvis and Frank Morelli.

In 2000, Carter penned a tribute to his friend Boulez on the occasion of the latter’s 75th birthday in the form a two-minute piano work entitled “Retrouvailles” (“Rediscoveries”). Having already offered musical birthday presents to Boulez for his 60th and 70th (both of which are quoted in this work), one awaits the French composer’s 80th birthday celebrations next year with interest, if only to see what Carter will do next. “Retrouvailles”, like everything else on this superb release, is proof, if any more were needed, that his skill as a composer and mastery of both short and long forms remain undiminished.

— Dan Warburton, paristransatlantic.com, April 2004

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Mode 128 (DVD)

First recordings are also a feature of Mode’s Elliott Carter disc Quintets and Voices (mode 128), although this is not unusual: Carter has been so prolific in old age that new works lie everywhere. The release makes use of current technology’s favourite toy, the DVD, combining the musical programme with a film record of a separate performance, and a lengthy interview with Carter and musicians. This proves a mixed blessing. With music so complex and mercurial, watching the film of the Quintet for piano and strings (1997) means taking part of one’s ear off the ball.

Ursula Oppens’s lips and eyes, always counting or glancing at the Arditti Quartet, give eloquent witness to the piano’s struggles to get a grasp on the strings, bustling about in their private world. But the music alone conveys this and more, the players chasing and teasing through a cat’s cradle of metres, intervals and speeds.

The 1991 Quintet for piano and winds and the song cycle Tempo e Tempi share the same combination of intellectual toughness and dramatic fire. Syringa, from 1978, is a thornier and chillier proposition. For anyone who loves contemporary music, this is a necessary disc.

— Geoff Brown, The Times (London), 20 February 2004 (4/5)

Elliott Carter

Quintets and Voices

Carter: Syringa; Tempo e Tempi; Piano Quintet etc.

Shelton/Solomon-Glover/Ensemble Sospeso/Milarsky/Asbury/Oppens/Arditti Quartet

Mode 128 (CD/DVD)

If discs of Elliott Carter’s music are no longer the novelty they were even a decade ago, there is still plenty of scope for new ones. The Mode collection is the first recording of the 1997 Quintet for piano and strings, typically muscular and argumentative – but it also includes outstanding performances of two major vocal works, one of which, Syringa, ranks alongside Carter’s greatest achievements.

Between 1847 and 1975, Carter composed no vocal music at all. His painstakingly slow progress in the 1950s and 60s towards a musical language all his own had been worked out purely in instrumental and orchestral works. But since the creative dam was breached, he has gone out to produce a succession of song cycles, all informed by contemporary American literature. Robert Lowell’s poetry was the source for In Sleep, In Thunder (1982), John Hollander’s for the 1994 Of Challenge and Love; while the starting point for Syringa was a poem of the same name by John Ashbery.

Yet it is not a conventional setting, neither a song cycle nor a cantata, but something in between. Ashbery’s densely allusive text is a retelling of the Orpheus myth, an